Aldeman: Yes, Average Teacher Salaries Are Down. But Many Individual Teachers Are Doing Just Fine

A lot of attention has been given lately to average teacher salaries. One commonly reached conclusion — which has proven true over the past few decades — is that average teacher salaries have not kept up with inflation.

But there’s a risk of taking this too far. While wages have declined, in real terms, total teacher compensation is up, due to fast-rising health care and pension costs. Moreover, averages reflect the composition of the underlying population. If lots of highly paid veterans retire and school districts replace them with lower-paid rookie teachers, the average will fall even though no individual saw a pay cut. Similarly, if a district decides to hire an extra teacher and brings in another entry-level rookie, that, too, will depress the average.

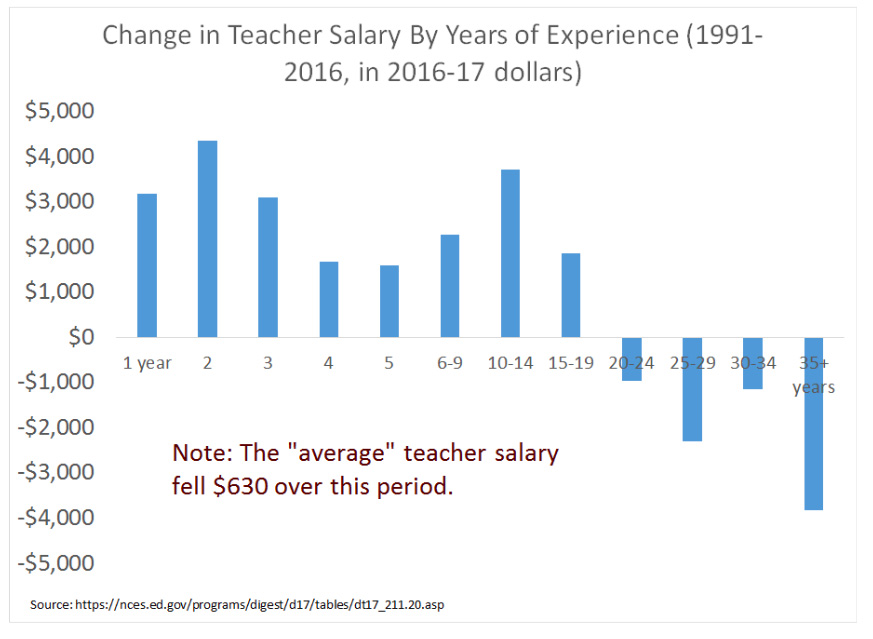

These are not mere hypotheticals. In fact, these trends have been playing out in schools all across the country. If you look deeper at the national salary trends, it’s clear that teacher pay is not falling across the board. Since 1991, the average teacher salary has fallen by $630 in today’s dollars. But look at the graph below, and you’ll see that this trend is far from uniform. Comparing apples to apples, all teachers with less than 20 years of experience have seen increases in pay. For example, salaries for teachers with 10 to 14 years of experience are almost $4,000 higher today, in real terms.

Again, multiple trends are playing out in this graph. The teacher workforce has gotten less experienced, meaning there’s a higher proportion of teachers on the lower end of their respective salary scales. And salary scales themselves may have changed somewhat to become more front-loaded. That front-loading would lower the average teacher salary calculation, but there’s evidence that front-loading salaries could have other benefits.

None of this explains how salaries have changed for individual teachers. To get an answer to that question, we have to use a different instrument than simple averages. There are a couple of ways to do this. At the district level, we can look at how a teacher would progress over time through the various steps and lanes on her district’s salary schedule (here’s an old example of this approach applied in Chicago).

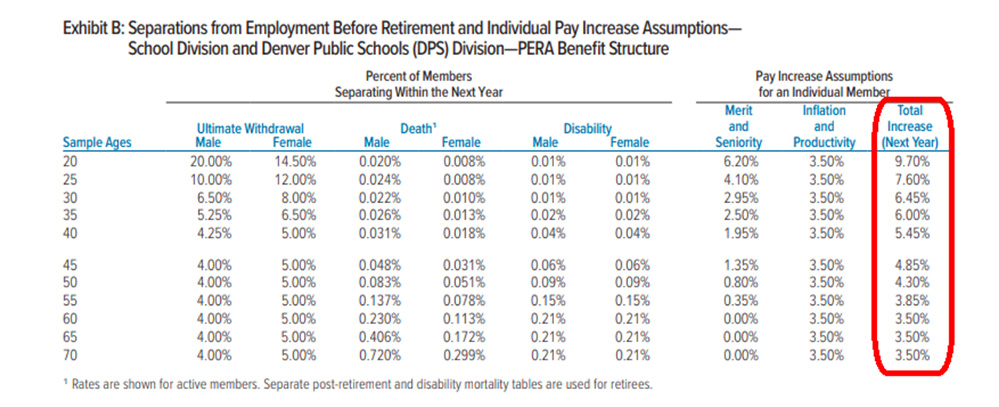

At the state level, teacher pension plans have been quietly making and releasing these calculations in their annual reports. Pension plans have to predict how much they’ll need to pay in future benefits, and to do that, they need to estimate how fast teacher salaries will grow over time. They have every incentive to make sure these predictions are accurate, since they’re basing high-stakes financial decisions on these estimates, so the plans update their predictions regularly after conducting “experience studies” to compare their past predictions with actual results.

As an example, consider the case of Colorado. On average, Colorado teacher salaries have fallen by 15 percent over the past 15 years, in real terms. But individual teachers are seeing raises. The table below comes directly from the Colorado Public Employees’ Retirement Association’s annual financial report. I’ve circled the last column, the state’s official estimates for how much teacher salaries will increase each year based on their age. For example, the state assumes teachers earn raises of 9.7 percent in their early 20s and raises of 7.6 percent in the second half of their 20s. Over time, those increases fall, but they always outpace the state’s assumed inflation rate of 2.4 percent.

Again, Colorado’s assumptions are based on hard data of what they’re actually seeing among their members. If we went solely off the statewide average, we might think that Colorado teachers have suffered from a severe pay cut. It’s possible that the rates of growth have slowed down over time, but individual Colorado teachers are still seeing salary increases.

In other words, the average is deceiving us, and Colorado is by no means unique. Teacher pension plans all across the country are telling a far rosier story, based on their internal data, than the bleak story we might glean if we rely only on simple averages.

Chad Aldeman is a principal at Bellwether Education Partners and the editor of TeacherPensions.org.

Disclosure: Bellwether Education Partners was co-founded by Andy Rotherham, who sits on The 74’s board of directors and serves as one of the site’s senior editors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)