Aldeman: We Think We Know How to Teach Reading, but We Don’t. What Else Don’t We Know, and What Does This Mean for Teacher Training?

All children need to learn to read, and humans have been teaching one another basic literacy skills for hundreds of years. Surely, if there’s one thing our schools need to know how to do well, it’s to teach reading.

But do they? As Emily Hanford shows in her latest must-listen documentary, the short answer is no. In fact, the reading problem has tremendous implications for how we should think about teacher training as a whole.

Hanford focuses most of her piece on the cognitive science about how students learn to read. Research shows that children become the strongest readers when they learn to sound out words and slowly build a knowledge base of words they have memorized. But many students are taught by guessing based on pictures, the first letter of a word or other contextual clues, even though the science suggests that these cueing strategies are ineffective.

Even if everyone understood the science of reading, we would have to somehow teach teachers how to implement those strategies. We’ve tried to spread scientifically backed reading strategies before, and it has not produced the desired results. At one point, we spent more than $1 billion a year on a federal program called Reading First that was based on the scientific findings of the National Reading Panel. After a disappointing research study (and politics), Reading First was eventually shut down.

We’ve also tried to embed the science on how students learn in teachers’ professional development. A high-quality, randomized field study conducted by the Institute of Education Sciences found that the program increased teachers’ knowledge about scientifically based reading approaches and improved their instructional practices but ultimately had no effect on student learning. If we can’t implement a successful reading program in experimental settings, it’s hard to imagine how it would spread across all 1.9 million elementary school teachers working across 50,000 primary schools nationwide.

Some people, including Hanford at times, jump to a third step. It makes sense that, if we could improve the skills of the new people coming into the profession, reading instruction as a whole would improve over time. This is especially urgent given that the workforce has changed and educators with less than five years of experience make up a growing share of all teachers.

But in this country, there are at least a few thousand preparation programs attempting to teach future teachers to teach reading. And yet, we have no evidence that any of those programs produce reading instructors who are better (or worse) than any others.

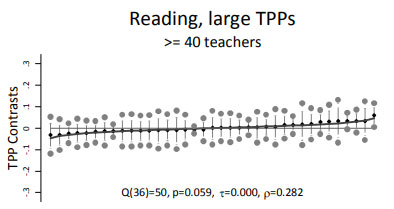

This is a scary realization, but it has implications for how much stock we should put in teacher preparation reform. When researchers Paul von Hippel and Laura Bellows went looking for meaningful differences in teacher preparation programs across six states, they found essentially none. The graph below shows what they found for large teacher preparation programs (TPPs) in Texas. Even looking at just the biggest programs with the largest sample sizes, they found that no program produced teachers who were statistically better or worse at teaching reading than any others.

Von Hippel and Bellows repeated this exercise for reading/English Language Arts teachers in Florida, Louisiana, Missouri, New York and Washington and again found little to no variation.

If we don’t know the right way to train reading instructors, what if we reduced the regulatory barriers for people to become teachers and let the schools figure it out? In 2016, my Bellwether colleague Ashley LiBetti and I outlined a vision for what that might look like. It would impose fewer barriers to entry to become a teacher but would then rely more heavily on in-service evaluations and supports to boost reading instruction. As we noted at the time, the information we have about teachers after just one year of teaching is seven to nine times as valuable as everything we know about them before they begin. And, although the evidence on most types of teacher professional development continues to underwhelm, there’s a growing body of research suggesting that in-service coaching could be a more promising approach.

Another lesson might be that reforms focusing on individual teachers aren’t the right lever to change reading instruction. It seems at least plausible that improving the instructional materials schools use to teach reading might be more effective than trying to shift the opinions and lesson plans of millions of individual classroom teachers.

Finally, it’s worth reflecting on what the reading literature suggests about the value of teacher training more generally. There’s widespread interest in improving the quality of teachers who enter our schools. But what if we simply don’t know enough about how to accomplish that goal?

That may sound defeatist, but if we can’t even teach reading, we should temper our expectations for everything else. Rather than trying to jam all the latest fads into teacher training programs and ensure that all teachers are “ready on day one,” we should put more emphasis on what happens to teachers once they enter schools and the systems in which they operate.

Chad Aldeman is a senior associate partner at Bellwether Education Partners and the editor of TeacherPensions.org. Bellwether was co-founded by Andy Rotherham, who sits on The 74’s board of directors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)