‘Adults Have Power. Students Don’t’: Cleveland Schools Aim Bias Lessons at Staff

From teachers, to bus drivers to custodians and lunchroom workers, the Cleveland school district is mandating anti-bias lessons

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The massive Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 drew calls for revamping what students are taught about racism, with demands for more Black history classes and for schools to ditch textbooks that gloss over uncomfortable historical events.

But in Cleveland, school officials have chosen a different route, one that may seem counterintuitive for a district that’s among the poorest in the nation, where Black students account for two-thirds of the enrollment.

Instead, district officials are mandating anti-bias lessons for all staff, ranging from teachers to bus drivers, to custodians and lunchroom workers.

“Equity behaviors are driven by the people who have power,” said Cleveland Municipal School District CEO Eric Gordon. “The adults have power. The students don’t.”

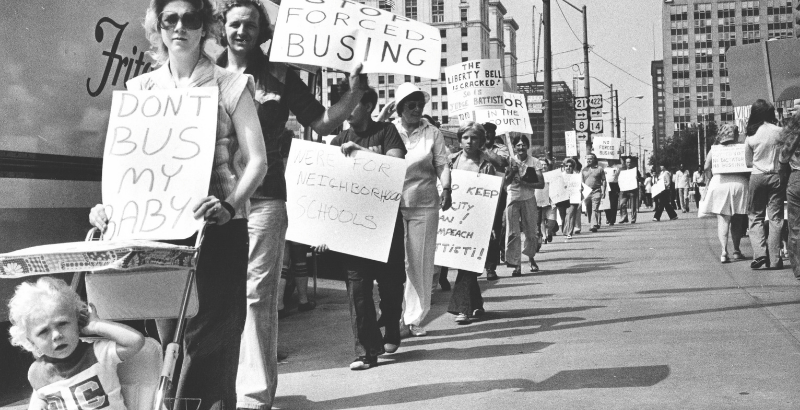

After nearly two years of planning, the district and teachers union have launched CMSD, Equity and Me, a six-lesson course on bias and historical inequities, such as redlining, white flight, segregated neighborhoods and busing, both nationally and in Cleveland.

The required course is currently being taken by all district administrators and front office staff. Starting in the fall all 7,000 district employees will begin the training.

The hope is that teaching staff about racial and economic inequities will change attitudes of the adults that deal with students and their families every day, which will then improve the atmosphere for students.

“Changing adult behavior is more important,” said Cleveland Teachers Union President Shari Obrenski, a former social studies teacher who helped build the new program.

“If you can change me, and the way that I communicate with my students, and my understanding of my students and my understanding of my community, then you’re giving me the tools to be more effective in the classroom.”

Gordon said he hopes the program goes well beyond day-long “equity-in-a box” programs he has sat through that recycle implicit bias discussions, supposedly offering a “safe space” for discussions, people congratulating each other on being “woke” at the end.

“If we’re going to do this, we have to be serious about it,” he said. I can’t say that there’s not others doing like this, but I think it’s something for us that is very carefully constructed.”

Demand for more teaching of racial issues has increased since the 2020 protests. Facing History and Ourselves, a national organization that trains teachers how to teach about social justice history and issues, says it increased its Teaching for Equity and Justice classes by 20 percent in 2021 to meet demand across the country.

Any teaching about racial biases in schools, whether for students or staff, has been a polarizing issue, as calls for better instruction have been met with Republican-led pushback lumping any teaching of inequities into a more advanced and nuanced college-level study known as Critical Race Theory.

In Ohio, a June, 2020 a state school board resolution condemning learning gaps between white and Black students, as well as“white supremacy, hate speech, hate crimes and violence in the service of hatred,” was reversed by new members of the same board in late 2021.

By teaching only staff and not students Cleveland’s new equity program avoids that hot button issue.

It also avoids complaints leveled in recent days against bias training in New York, California and other states that may be partly paid for with federal COVID-relief dollars: Cleveland’s effort, so far, has been covered by a $200,000 grant from the Cleveland and George Gund foundations.

Gordon and Obrenski know portions of the CMSD, Equity and Me program will touch nerves, but they are not shying away from topics that might make the district a target.

“We do and should teach a fully inclusive history, both world and American history – even the parts we don’t like,” he said. “There’s no country on the globe that doesn’t have some parts of their past that they are not proud of.”

And Obrenski said union leadership won’t have much tolerance for teachers that want to avoid the sessions.

“By and large, as I’ve said, the membership is ready,” she said. “But in segments where we may have members that are reluctant, they’re going to move. There is no choice. This has to happen.”

The six 90-minute lessons, which are still being adapted as they are rolled out, will all fit into school days, usually within planning and professional development time built into teachers’ weekly schedules already.

The first, which will be taught by district officials, will cover the aims for the classes and the district’s goal of better equity and inclusion for all.

Then, a local nonprofit called Teaching Cleveland, will handle the second lesson using a “Groundwater” metaphor – a comparison of the district’s culture to ecosystems that can let life thrive or that can have contamination that harms life within it.

If a lot of fish die in a pond, the lesson asks, is the problem the fish? Or is it something about the water? From there, the session asks whether gaps in learning, income, crime and other indicators between different racial groups are the fault of the people, or the system around them.

“What we introduce is this notion… that there’s something going on in the groundwater of our society that has led to inequities,” said Marcy Shankman, who oversees the district’s professional development. “And what we want to do is understand what it means to live in a racially-structured society where perhaps there’s something wrong in the groundwater, that there are pollutants there.”

Teaching Cleveland, which was created by local teachers to help teach more local history, will then teach district staff about inequities in Cleveland history, ranging from redlining to segregation and concentrated poverty in the city.

The fourth and fifth sessions will be covered by Facing History and Ourselves, which already has strong Cleveland ties and even helps run a high school in the district. One will cover the history of race and education in the U.S., while the other will cover how individuals can confront their own biases and change the culture around them.

The sixth, which is still being developed, will have attendees work on ways to counter problems they have just discussed.

District officials and Greg Deegan, founder of Teaching Cleveland, said the last session will give staff time to reflect on how inequities affect them, their school and their community and how they can change parts of them.

“It keeps equity in the forefront of their minds as they do their work,” Deegan said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)