Lessons From a Global Reckoning: Ohio’s ‘Whitewashed’ History Lessons Need Brutal Truths, Unheard Voices, Cleveland Teachers Say

This is the fifth story in a six-part series, “Lessons From a Global Reckoning,” in which The 74 examines how issues of race are taught — or ignored — in America’s classrooms. As the pandemic continues and after nationwide protests following the death of George Floyd, this series seeks to take a hard look at how educators are tackling these painful but important issues. Read the rest of the pieces as they are published here.

When Kendall Smith was taught about Reconstruction of the American South after the Civil War, she was told it was the nation’s attempt to right the wrongs of slavery.

“They said that was the purpose and that they did it,” said Smith, now a senior at Cleveland’s MC2STEM High School. “I was never taught that isn’t what happened.”

Smith wishes she had learned about Reconstruction’s failures — of how slavery was replaced with sharecropping and Jim Crow laws — and history’s blunt truths without “watering down” uncomfortable facts.

“We should know everything … the good and the bad,” she said. “It’s hard to move on when we don’t know everything.”

How well schools in Cleveland handle racial issues is under increasing scrutiny after the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter protests that followed this summer. For many, making sure the district’s students — 64 percent of whom are Black — know the context behind racial issues today is a priority.

The same scrutiny is happening for schools across Ohio, though not always with the same local urgency in a state that’s 82 percent white and 13 percent Black.

Ohio’s state school board put the issue at the forefront last week, when board members criticized persistent learning gaps between white and Black students and condemned “white supremacy, hate speech, hate crimes and violence in the service of hatred.” With a 12-5 vote, the majority-white board called for anti-bias training for themselves and Ohio Department of Education employees.

The board also directed the department to re-examine state tests and learning expectations in all subjects to make sure that “racism and the struggle for equality are accurately addressed.”

“We must confront our own bias,” Board President Laura Kohler said. “We must learn about how racism impacts society and how to recognize and eliminate racism perhaps even in our own hearts. We must begin to understand people who have experienced things that we have not.”

A small but growing number of critics say an honest review of state expectations for history classes will find that they downplay racial and social aspects of the nation’s past, burying them in a rush to teach other material on state tests.

“Everyone’s addressing racism now, but our curriculum doesn’t really allow us to address it,” said John Adams, a Cleveland high school history teacher who has presented his concerns to state Superintendent Paolo DeMaria.

Adams and others say Ohio teaches slavery and the Civil War too early, uses euphemisms like the “forced migration” of Black slaves and treats wars, not social issues, as the dominant part of history.

Shari Obrenski, who taught social studies for 21 years in Cleveland before becoming head of the Cleveland Teachers Union in April, agrees with Adams’s assessment.

“The social studies curriculum is still very much whitewashed,” she said. “That’s how social studies has been taught for generations.”

Schools or teachers that want to present a broader look have to fill in gaps with extra work or classes.

For many, that takes a separate Black history class. But those are usually electives, like at nine of Cleveland’s 32 high schools, and not required classes.

Black history classes should be mandatory for all students, says Lavora “Gayle” Gadison, the social studies content manager for the Cleveland school district. Other teachers in Ohio are also quietly exploring whether Ohio could require Black history classes statewide.

Gadison said Cleveland students need Black history classes to see patterns of racism over time and not see it just as isolated events.

“You have these protests, and people are outraged by the treatment they’re seeing by the police,” said Gadison. “But this is not brand new. If everybody knew this history, then folks would know that this is just a continuation.”

Gadison has also tried to supplement Cleveland’s history lessons by inserting portions of a “Teaching Tolerance” anti-bias curriculum from the Southern Poverty Law Center into eighth-grade history outlines. She plans to add Teaching Tolerance to extra grades soon.

The Teaching Tolerance additions would highlight that slavery was the central cause of the Civil War, that slavery shaped beliefs about race and that white supremacy was a by-product of slavery.

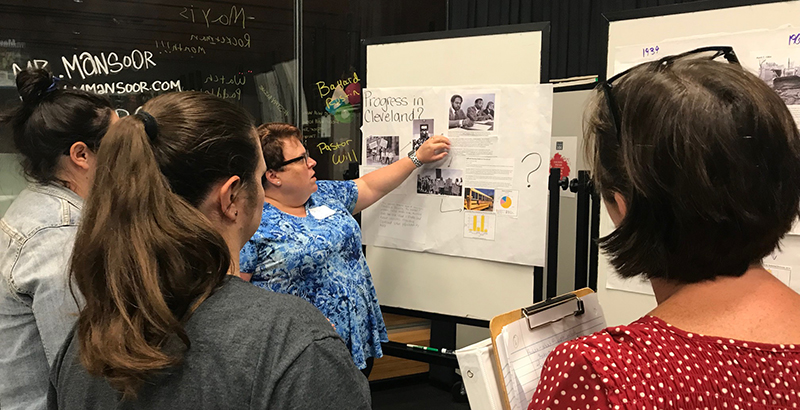

The Cleveland school district, like schools in cities like Chicago and Memphis, also works with Boston-based Facing History and Ourselves, a national group that provides teaching materials and training to add depth to history and English classes.

“There is a lot of pain in this nation’s history, tremendous pain, tremendous brutality,” said Kristen Miller, a social studies teacher at Cleveland’s John Marshall School of Information Technology. “Do we teach that raw pain? No.”

Facing History helps her cover those issues in a meaningful way.

“It taps into so many unknown and often unheard-of voices in history,” said Miller, who has used Facing History to add perspective to her classes for years and just started teaching a Black history class last year using Facing History’s approach. “There’s definitely room to bring in voices that are not as strongly represented in the standards.”

Facing History’s partnership with the Cleveland school district has been growing over time. The district has a Facing History high school, and the organization works closely with four other schools to bring lessons to students and with another 18 schools to provide materials or training for teachers.

Standards at the root

A top concern is Ohio’s choice to teach slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction in eighth grade. The subjects are not revisited in high school, unless individual teachers choose to.

“You can teach kids about these things when they’re younger, but then they don’t have the cognitive abilities to fully grasp the magnitude of what happened,” Adams said.

Adams has already asked the state superintendent to make the Civil War era part of high school history classes to cover that hole.

Adams and Gadison have also suggested changing Ohio’s eighth-grade standards to highlight slavery and colonialists’ mistreatment of Native Americans throughout the year. They would also adjust the standard covering Reconstruction to highlight constitutional gains for former slaves but also Southern opposition and rise of the Ku Klux Klan.

“This is one of the most important statements,” they note. “We must get it right.”

Racism as the central issue?

At the core of the debate is how dominant racism was in shaping this country. Though some, like Adams and Gadison consider it central, others don’t.

At last week’s school board meeting, two residents objected to the Ohio Department of Education listing The New York Times 1619 Project as a resource for teachers. They objected to its claim that “out of slavery grew nearly everything that has truly made America exceptional: its economic might, its industrial power, its electoral system.” They said the claim overstates history, is inaccurate and should be removed from the department’s list of resources.

Ohio Department of Education officials defended its accuracy, and it remains.

State school board members also were divided over the board’s anti-racism resolution. While board member Linda Haycock talked about her gradual understanding of how white privilege has benefited her, board member Mike Toal was uncomfortable referring to privilege in the resolution.

Toal said he doesn’t understand the concept well, much like many residents who might push back against the overall effort.

“It’s a very contentious concept,” said Toal, who is white; he voted for the resolution despite his concern. “Maybe it’s not as contentious in certain segments of the population.”

Board member Lisa Woods, who is also white and represents a mostly white region about 45 minutes southeast of Cleveland, wanted clear definitions and proof of the systemic racism and hate speech condemned in the resolution. She read several letters that challenged any statement that Ohio has systemic racism since it was never a slave or Jim Crow state.

“These are serious but unproven accusations,” said Woods before voting against the resolution.

Board Vice President Charlotte McGuire, who is Black, also voted against the resolution.

“I don’t believe in systemic racism,” she said, explaining that systems are just made up of individuals who determine how systems work.

And she questioned the idea of privilege, saying she has succeeded even after attending segregated schools in Memphis growing up, because adults encouraged her.

“When you talk about privilege … am I privileged?” she asked. “I could talk about Black privilege, for example, because of my achievement in life. A lot just has to do with the hearts of people.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)