Act 10, Scourge of Wisconsin Teachers, Faces Uncertain Future in Court

The controversial 2011 law improved academic outcomes as it weakened unions, research shows. Now a legal challenge could wipe it away.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

More than a decade later, Angie Bazan can remember a particularly vivid encounter during the protests to save Wisconsin’s teachers unions.

For several weeks in February 2011, she was one of tens of thousands of demonstrators who packed the Wisconsin state capitol to protest against legislation that aimed to shut down collective bargaining for public employees. One night, caught amid a swell of activists belting the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome,” she suddenly noticed that she was standing a few feet from Jesse Jackson, who had traveled to Madison to spur resistance to the Republican-led bill.

To Bazan, a social studies teacher in the nearby town of Deerfield, it seemed that she was living through one of the historic scenes she often described to her high school students. Though the GOP had won a sensational victory in the previous fall’s elections, capturing both chambers of the state legislature and electing the ambitious conservative Scott Walker as governor, the fight wasn’t over. Marching in solidarity with progressive heavyweights like Jackson, and with the eyes of the labor movement on Wisconsin, she and her colleagues could still prevail in the struggle to keep their hard-won rights.

“You could see the Democratic legislators waving to us from the windows of their offices,” she recalled. “We really believed that we weren’t alone anymore, that these people were in it with us, and that it might force the legislature to back down.”

But Walker and his allies didn’t fold.

Instead, after another month of political theatrics, they enacted the Wisconsin Budget Repair Bill, better known to history as Act 10. Its passage was a staggering setback for labor, stripping public-sector unions— with notable exceptions, such as police officers and firefighters — of virtually all bargaining powers.

Before the crowds dispersed, the bill had already started to reshape the K–12 landscape in Wisconsin, both by shoring up district finances and straitjacketing unions’ political sway. While Walker ultimately lost the governorship in 2018, his signature accomplishment stands as a model for conservative governance in a purple state.

After a major judicial ruling last year, however, it is unclear whether Act 10 will stand at all for much longer. In December, a state circuit judge struck down the law’s constraints on collective bargaining, declaring the exemptions for first responders a violation of Wisconsin’s equal protection doctrine. Even with the judgment stayed pending an eventual appeal to the state Supreme Court, some political observers are weighing the potential of a massive shift in state policy.

Fourteen years under the Act 10 regime have cast ripples across much of Wisconsin. Overall teacher compensation has fallen substantially, along with education costs to cash-strapped districts. Academic research has found that the weakening of workplace rights freed up school systems to change the way they structure pay, rewarding the best instructors while simultaneously lifting student achievement higher.

But as top performers found new opportunities, new divisions opened up among districts and even genders, with male employees often receiving higher salaries than their female coworkers. Solidarity continued to dissolve as formerly mighty unions lost members and prestige. And a lingering hurt still hangs over many Wisconsin teachers, who feel that the Republican triumph was built on their misery.

Disheartened by what she described as an increasingly hardline stance from her school board, Bazan soon moved to another district. “They have a union on paper, but it has no power,” she said.

The restoration of their power would be a cause for immense celebration, even as most experts agree that some of the changes to education spending and teacher influence likely cannot be altered. Alan Borsuk, a senior fellow in public policy at Marquette University Law School, said that while teachers had largely “learned to live with” the changes to their bottom line, the blow to their esteem remained.

“In some ways, the biggest impact of Act 10 was what it did, intangibly, to the teaching field,” he said. “So much hostility to teachers came out during that time, and the damage to teacher morale continues to this day. It just hasn’t been a cheerful profession for a lot of people.”

***

The shock delivered to teachers resulted primarily from a rollback of union strength that could only be called historic. As the first state to allow public employees to organize, bargain, and strike, Wisconsin helped trigger a revolution in workers’ rights a half-century before Act 10; in its wake, that mass movement suffered its worst defeat in a half-century.

After the expiration of the collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) that were in effect when the law was signed, unions were forbidden to negotiate over fringe benefits or working conditions. Though they retained the right to negotiate salaries, they could not secure raises that outpaced inflation in a given year. Further, teachers would be required to make sizable contributions to their own pensions and benefits, overturning generous perks that had been won at the bargaining table years earlier. Finally, organizing itself was made harder by a new mandate for unions to hold recertification votes each year to remain active.

Kim Kohlhaas was then in her 15th year as an elementary educator in Superior,, a lakefront city near the border with Minnesota. She described the time she spent there before the adoption of Act 10 as a “dream job,” but the impact of the change made itself felt within months.

“Our contract was 28 pages long,” said Kohlhaas, who now serves as the head of the American Federation of Teachers’ Wisconsin affiliate. “It became one page, and that was just recognizing that we existed.”

No longer obliged to deal with unions like the AFT over regular salary increases, school districts were responding to their newfound freedom exactly as Walker had intended. Some kept their existing salary schedules more or less intact, but many others began experimenting with merit pay schemes that awarded bonuses for employees who attained additional professional credentials or earned high grades in the state’s teacher rating metric.

The effects, detailed in a series of studies conducted by Yale economist Barbara Biasi, have largely been promising.

In a paper published in 2021, Biasi compared Wisconsin districts that moved toward a flexible pay model with those that continued setting compensation on the basis of seniority, as had largely been the practice before Act 10. Collecting both statewide salary records and data on teacher value added (a measure of effectiveness that reflects students’ improvement in standardized test scores), she found that highly successful teachers in “seniority-pay” districts tended to find new positions in communities offering some form of merit pay, meaningfully increasing both average teacher quality and student scores in those places.

According to Biasi’s estimates, the value-added of those job-movers was 60% higher than their counterparts who chose to leave their districts after the adoption of flexible pay structures. In addition, some proportion of relatively lower-performing teachers simply stopped teaching in public schools, whether to leave the profession entirely or to work in private institutions.

In a follow-up study circulated this spring, Biasi extended her findings up to 2016, five years after Republicans pushed the reform through. In the years prior to 2011, she found, seniority was practically the only factor determining teacher pay: A professional over 57 years old earned, on average, 88% more than one who was 24 years old. But after the pre-Act 10 contracts expired, those career veterans earned slightly less than they previously had, only making 73% more than their most junior colleagues.

As the gap between older and younger educators flattened, student achievement — especially for children from low-income families — saw a significant bump throughout the state, with standardized test scores climbing higher statewide each additional year after Act 10 was passed.

Biasi observed that no district has switched to a fully pay-for-performance system, in part because superintendents and principals do not typically have access to value-added statistics themselves. Instead, they were taking advantage of the autonomy around pay to favor employees whom they saw as working harder and more capably to boost learning.

“They’re just using this flexibility to retain teachers that they consider to be better, or at a higher risk of departing for a nearby district, or who are in positions that are particularly difficult to staff,” she said.

***

Academic improvements like those revealed in Biasi’s research would be welcome anywhere. But even among its Republican supporters, Act 10 was not principally sold as a policy to improve schools.

Instead, it was seen as a way of heading off fiscal calamity. Like many states during the Great Recession, Wisconsin faced a large revenue shortfall in early 2011. When he took office, Walker vowed to close the structural deficit, arguing that local governments “don’t have anything to offer.” Either Act 10 would be approved by lawmakers, or thousands of state employees had to be laid off.

Nearly a decade and a half later, the budgetary picture is much brighter, with the state accumulating plentiful cash reserves. After a dip during the financial crisis, Wisconsin has finished in the black every year since, with its total debt recently falling to its lowest level since the Clinton presidency.

In particular, conservatives tout an employee pension fund that was fortified over the long term by the contribution requirements included in Act 10. According to a report from the nonprofit Equable Institute, the funding ratio for Wisconsin’s retirement programs exceeds 100%, ranking the sixth-best of any system in the country. The Pew Charitable Trusts has found that the state effectively balances against the risk of an investment downturn while also insulating retirees from inflation.

Borsuk, a frequent critic of state Republicans who is married to a retired teacher, said the financial case for the law was “clear and compelling,” especially when contrasted with the debt and potential insolvency of neighboring Illinois, where state employee pension funds are ranked among the most over-extended in the nation.

“It saves school districts a huge amount of money, and some of them were facing fairly dire circumstances in 2009 and 2010,” he argued. “Teachers had to pay more to support their benefits, but to be honest, they got used to that, and life went on.”

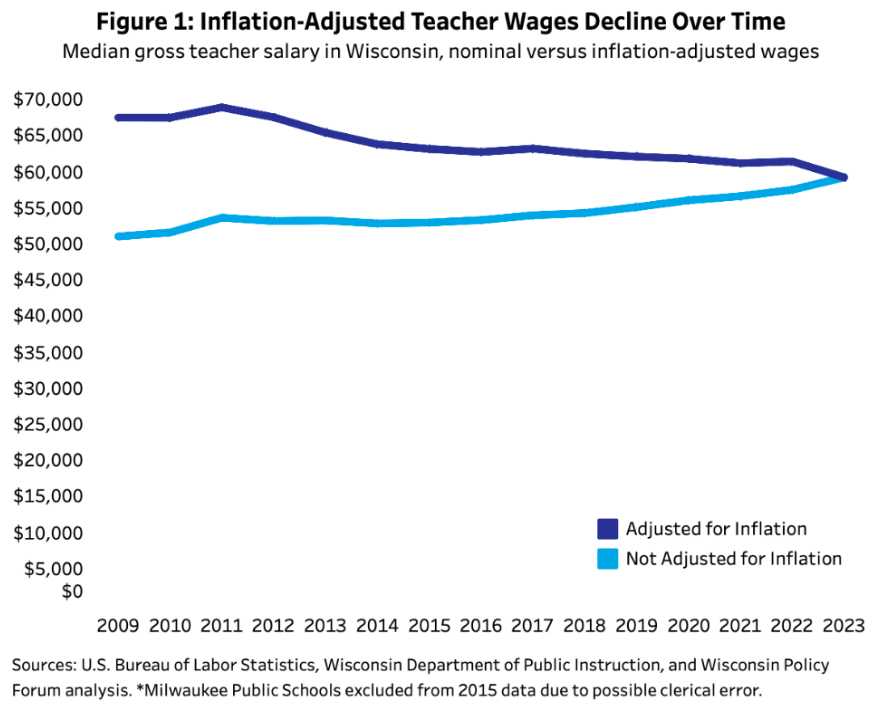

Yet many schools and districts aren’t as sanguine. Wisconsin’s annual spending per K–12 student, which was 11% higher than the national average when Act 10 was being debated, was 6% lower just a decade later. Between 2002 and 2020, the state’s K–12 spending grew at the third-slowest rate anywhere in the country. After adjusting for inflation, the median teacher’s take-home pay fell from $68,949 in 2011 to $59,250 in 2023, according to the nonpartisan Wisconsin Policy Forum.

That trend resulted partially from an exodus of older teachers in the first few years after the law went into effect — Biasi found that the exit rate rose from 5% to 9% in its immediate aftermath — and their replacement with lower-paid novices. Headcounts stabilized over time, but Kohlhaas described a period of heightened churn that saw schools’ relationships with families frayed as familiar and well-liked staffers left for other districts.

“The first couple of years after Act 10, the retirement parties were not celebrations,” she said. “The teachers, the secretaries, the nurses, the bus drivers, the paraprofessionals — usually the first faces that students see in the morning — were changing every year, or sometimes mid-year.”

***

In a job market that was quickly becoming much more fluid, union membership also began to lose its appeal. School staff were increasingly on the move between districts, and the benefits of belonging to an organization with a severely narrowed scope of action were not always clear.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the proportion of union members in Wisconsin’s workforce fell by nearly half, from 14.2% to 7.4%, between 2010 and 2023 (since that figure includes workers from all sectors, the drop for government employees is likely much steeper). A report from the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty, a right-leaning think tank, showed that the total number of unions holding annual recertification votes across the state declined from 540 in 2014 to 369 in 2018.

The largest teachers’ union in the state, the Wisconsin Education Association Council, experienced a dizzying loss of manpower and organizing heft. A 2019 study conducted by a pair of researchers at the University of Wisconsin found that WEAC was forced to restructure and cut its staffing by about two-thirds. The retrenchment was made necessary by a freefall in the collection of dues, the payment of which was made voluntary by Act 10.

The loss of paid organizers could be offset, in part, by the efforts of teacher volunteers. But the union had no ready replacement for the millions of dollars in government relations funds that had suddenly evaporated; WEAC went from being one of the biggest lobbying forces in Madison to a second-tier player virtually overnight.

Spillovers into elections were inevitable. In a 2024 paper, Yale’s Biasi studied the effect of Act 10 on political donations during gubernatorial races in 2012 and 2014. Across all Wisconsin school districts, she calculated that the reform depressed contributions to the Democratic Party by 33.1 per 1,000 people, and by over 50 per 1,000 teachers. Scott Walker’s vote share increased by about 2 percentage points as a result.

Unions “essentially stopped donating money to Democratic political campaigns after the reform because there was a huge drop in revenues coming in.” Biasi said. “Membership went down, and so they just became increasingly less influential actors post-Act 10.”

Gender politics were inflamed as well. Once collective bargaining was invalidated, individual teachers were left to negotiate their salaries by themselves — typically at the start of their work in a new school. But while these interactions occurred at the individual level, a significant pattern made itself felt over the course of several years: Male teachers were making more than female colleagues of similar age, effectiveness, and experience.

Biasi discovered that, two years after the expiration of CBAs that had been in effect when Act 10 was signed, salaries for male staff were .4% higher than those for comparable female staff, a gap that grew to 1% after another three years. That estimate would be the equivalent of $540 per year, mostly attributable to women being less likely to negotiate over pay when offered a job. While hardly lavish, the disparity could be seen as adding insult to the injury already sustained by an overwhelmingly female profession.

***

Whether those wounds will be mended anytime soon is difficult to say.

After the ruling issued in December, the fate of Act 10 will not be decided until an appeal is heard by the state Supreme Court. In all likelihood, much of 2025 will pass before a final ruling is delivered — most likely not until the election of a new justice in April. The court’s liberal faction holds a 4-3 majority after Democrats staked an extraordinary sum to flip a Republican-held seat in 2023. This spring’s contest is also drawing national attention, with White House advisor Elon Musk contributing $1 million to support the Republican candidate.

Foes of the law were hopeful even before conservative Justice Brian Hagedorn announced in January that he would recuse himself from hearing the case (Hagedorn had previously defended Act 10 in his capacity as Gov. Walker’s counsel). But some believe that even the wholesale rejection of the law wouldn’t restore to labor the primacy it formerly enjoyed.

Borsuk remarked that, with the expiration of federal pandemic aid last fall, local districts would be hard-pressed to grant generous new contracts to reinvigorated unions. Cities and towns have already had to dig deep to finance increases in school spending, passing a record number of property tax hikes last fall to keep up with expenses.

“School districts in Wisconsin are under an enormous amount of financial pressure in every part of the state,” he said. “There’ll be some change, but it’s not like the golden era can return; there isn’t much gold.”

But to Bazan, the prospect of an overturned Act 10 is too promising to dismiss. More than simple financial rewards, she said, she looked forward to regaining “a voice outside the classroom.”

“A world without Act 10 is one where teachers get back the respect that we lost 14 years ago,” she said. “When we lost that seat at the table, we lost a lot of that respect as well.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)