DPS is in financial crisis and officials say there simply isn’t money to fix facilities. The district’s long-term debt

totals $3.5 billion, according to one

report. That

means about $3,019 of the $7,296 DPS gets from the state in per-pupil funding goes towards paying down debt — and not into schools and classrooms. The district has

said it will run out of money in April.

DPS has faced massively declining enrollment, largely because of decreased population in the city as a whole, and increased competition from charter schools who are drawing students away from the district. The number of school-age children in Detroit dropped from nearly 200,000 to about 120,000 between 2000 and 2013. And in 2013, just 42 percent of Detroit kids attended DPS, compared to 85 percent in 2000.

Fewer kids, means less money, because schools in Michigan are funded based on the number of students they enroll. The district has responded by shuttering or reconfiguring 230 schools since 2000 and dramatically downsizing staff, but not fast enough as certain fixed costs, such as pension obligations and bond debt, are difficult or impossible to reduce at the same rate DPS is losing students. A variety of short-term loans has been converted into long-term debt. Put simply, “the revenues decline faster than the cost,” according to David Arsen, a professor at Michigan State.

Last year, Moody’s downgraded the district’s credit rating, explaining, “Absent enrollment and revenue growth, fixed costs will comprise a growing share of the district's annual financial resources and potentially stress the sufficiency of year-round cash flow.”

So are charter schools helping or making things worse?

That’s a hotly disputed question.

Charter school supporters say the charters — in which nearly half of Detroit students are enrolled — give parents a choice to move their children out of struggling district schools. And many have as charter enrollment numbers continue to climb and district enrollment spirals downward. There is evidence charters in Detroit moderately outperform DPS in both math and reading tests, based on data through 2011.

On the other hand, some argue that charters and DPS aren’t on an even playing field, so making these sorts of comparisons isn’t fair. Charters don’t have the same legacy debt as the district, and thus may be able to put more money into schools. DPS, meanwhile, is stuck in a vicious cycle: declining enrollment leads to funding cuts which leads to a reduction in services and school quality — which leads to more declining enrollment. Evidence suggests that Michigan charter schools can negatively affect school district finances. According to an analysis by Rutgers professor Bruce Baker provided to The Seventy Four, charters in the Detroit area receive about the same per-pupil funding as district schools as a whole.

1

A 2014 investigation by the Detroit Free-Press found that there has been limited oversight of Michigan charters , allowing public money to go to waste and poor-performing schools to stay open. Some charter school supporters have

called for improving performance standards and accountability in the sector. The majority of Michigan charter schools

operate for profit.

Who is organizing the sick-outs?

The protests appear to be largely organized by a grassroots teacher group called the

Detroit Strike to Win Committee, headed by Steve Conn, a DPS teacher and the former president of the Detroit Federation of Teachers. Another group called DPS Teachers Fight Back — which refers to itself as a “union within the union” — also is supporting the sick-outs. The teachers also seem to be

backed by the activist group By Any Means Necessary.

Conn was ousted as president by the Detroit Federation of Teachers’ executive board in August 2015 based on several misconduct charges, including illegally cancelling meetings and failing to pay his own union dues. Conn, who was elected in January 2015 on a platform of more militant unionism,

said the charges were “concocted” and the internal trial was “secret [and] McCarthyite.”

In September, a majority of voting unions members supported reinstating Conn as president, but he fell short of the two-thirds required to overturn the executive board’s decision. At the time, Conn said he

planned to form a new union. As president, Conn organized a protest of state policies, leading to the

closing of 18 Detroit schools last April, as nearly a fifth of teachers were absent.

Conn — who refers to himself as the “elected president of the DFT” — isn’t done fighting for his old job: An appeal before the American Federation of Teachers is still pending.

What’s the union’s position on the sick-outs?

Interim president of the 4,000-member Detroit Federation of Teachers Ivy Bailey (who replaced Conn) said, “We haven't sanctioned the sick-outs, but I want everyone to understand the frustration.” A statement on the union’s

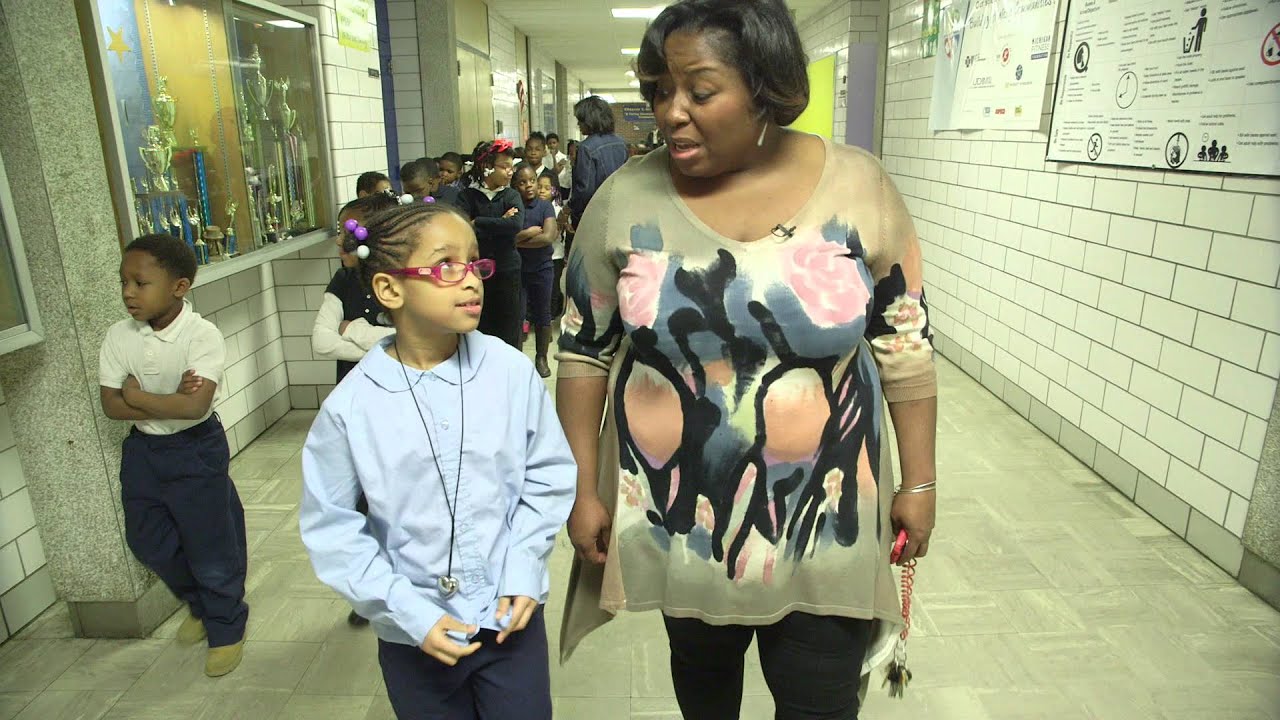

website encourages teachers to report to work. Bailey has also emphasized just how bad conditions are,

saying, “We refuse to stand by while teachers, school support staff and students are exposed to conditions that one might expect in a Third World country, not the United States of America."

American Federation of Teachers (AFT) President, Randi Weingarten, recently visited Detroit to highlight conditions in the schools; the AFT also produced a

video on the state of DPS schools.

And, as noted, the union has just sued the district over the schools’ conditions.

What response have the teachers received?

However Snyder, the Republican governor, condemned the teacher absences, saying, “What I would say is it’s really unfortunate because it’s coming at the expense of the kids. There are other venues and ways — if people have issues or things that they’d like to present — to do that. They shouldn’t be doing it at the expense of not having kids in class, and that is something that we’re carefully monitoring.”

Republican state legislators have discussed legislation to remove teaching licenses from those who participate in the sick-outs.

Is a strike coming?

That’s not clear. Conn has argued repeatedly that teachers ought to strike, while Bailey, the union leader, also reportedly made robocalls to teachers saying a strike may be necessary. It is illegal in Michigan for public sector employees to strike. Conn has

said, “Sometimes you’ve got to break the law to make the law better.”

What’s the emergency manager’s role?

DPS has been run by a state-appointed emergency manager since 2009 after the state superintendent declared the district was in a financial emergency. Soon after the emergency manager took control, a district-wide audit

uncovered rampant fraud and corruption under the old system. But since the state took over, there have been four emergency managers and DPS has only fallen deeper into debt.

DPS was originally taken over by the state in 1999. In 2002, the district had a significant budget surplus, but by the time DPS was returned to city control in 2005, through an elected school board, there was a $200 million

budget deficit.

Other Michigan school districts and cities — populated largely by low-income, black residents — are controlled by an emergency manager, and some have argued that the policy amounts to racist disenfranchisement. In 2012, Michigan voters

repealed the state’s emergency manager law by referendum, but a similar statute was promptly

reinstated by the legislature in a lame-duck session — and this version

cannot be repealed by popular vote.

Does this have anything to do with the lead poisoning in Flint?

Some have made a connection between the two, since both the city of Flint and DPS have state-appointed emergency managers and both have a poor and largely black constituency. In fact, the current emergency manager of DPS, Darnell Earley, had

the same job in the city of Flint from 2013–2015 and it was under his leadership that the city’s water source was transferred, resulting in lead-tainted water.

Many have argued that the two incidents show that the emergency manager law should be scrapped.

Is the whole public school system operated by DPS or charters?

No. The Education Achievement Authority, usually called EAA, is a separate set of schools jointly run by DPS and Eastern Michigan University that was created in 2011 to manage low-performing schools. The district was formed by the emergency manager and the regents of Eastern Michigan University, who are appointed by the governor. Fifteen Detroit schools are operated by the EAA and the stated goal was to provide more autonomy to principals, teachers and parents.

The EAA quickly drew controversy, in part because of its schools’ use of an online-learning program, as well as the fact that it was established with little local input. A Michigan State University report

described EAA as a “policy trainwreck”; another

analysis found that students in the EAA had made few gains in student achievement. The FBI and U.S. Attorney’s office

opened up a corruption probe of the EAA last year; this month a former EAA school principal was

indicted and pleaded guilty to charges of bribery and money laundering.

Snyder has recently expressed willingness to disband the EAA if his other proposed changes to Detroit schools are approved.

What solutions have been proposed to address the financial issues in DPS?

Earlier this month Snyder proposed bills that would:

- Separate DPS into two separate entities, an “old” and “new” district: one designed to pay down the district’s existing debt, the other to operate schools.

- Provide $715 million in state money to help the district reduce its debt.

- Create an interim school board, with five members appointed by the governor, and four appointed by the Detroit mayor.

- Transfer partial district control to a locally elected school board by January 2017 following a November 2016 election. The elected board would have only limited power over the schools and would not appoint the superintendent.

A few of the policies mirror recommendations from an influential group called The Choice is Ours, which is comprised of a broad coalition of city and state leaders. In a

statement, the group listed a number of concerns with the proposal, including the lack of full local control. Detroit legislators have also said the return to local control is not fast enough and

does not vest full authority in the school board.

Another key sticking point is how charters would be held accountable. Democratic lawmakers and the mayor want to give a citywide commission the authority to close low-performing charters. After Republican legislators and charter advocates expressed opposition to this measure, the governor did not include it in his proposed bills.

It remains unclear where the $715 million would come from — legislators from outside Detroit worry money that would otherwise go to their school districts would be diverted to DPS. It’s also unclear what would happen to the Education Achievement Authority.

Would the plan solve the district’s fiscal problems?

There are reasons to be skeptical. Some

worry that Snyder’s proposal does not address the structural issues that DPS has, particularly how schools across the state are funded. The proposed $715 million would only cover a fraction of the district’s 3.5 billion long-term debt. Splitting the district into two separate entities

won’t do much, including for the fundamental issue of declining enrollment.

The Choice is Ours coalition recommends moving to a weighted student funding system that “will more accurately account for students’ different learning needs” by providing more money for more disadvantaged students. For instance, the group points out that although DPS receives extra funding for students with special needs, it’s not nearly enough to provide necessary services to those students.

Rebecca Sibilia, of the national nonprofit EdBuild, which advocates for equitable funding, agreed that Detroit gets shortchanged from the state. According to EdBuild’s research, in state and local dollars, DPS spends about as much as its wealthy suburb, Grosse Pointe, at more than $12,000 per pupil. But Detroit serves a much more disadvantaged — and therefore more expensive to educate — student population and has higher property taxes to make up for its significantly lower property values. A

report from the Education Law Center gives Michigan a C based on how fairly the state distributes money to its schools. Sibilia, like The Choice is Ours, advocates for a more progressive approach to funding.

So what’s likely to happen next?

The only solution involves a significant amount of revenue or reduction in costs, perhaps through debt restructuring. What actually happens is really a question of what can get through the political meat grinder, according to Eric Scorsone, an economist at Michigan State University. Raising revenue may be politically difficult, but using money from the existing state education fund would result in pushback from other parts of the state.

Some have even discussed bankruptcy to restructure the debt. (The city’s bankruptcy proceeding that allowed it to get out from under $7 billion in debt and invest $1.5 billion in improved city services

did nothing to help the schools' fiscal crisis.) But doing so would be complicated because the entire state’s pension system would be affected, according to Scorsone, and the Michigan constitution leaves the state with the bill for any debt that the district walks away from. Unions would surely

fight any attempt to cut pensions.

But something has to give. “Clearly the system is unsustainable right now,” said Scorsone.

Footnotes:

1. This analysis accounts for the fact that some students — such as those requiring special education services — are more expensive to educate. In other words, charters and district schools receive about the same per pupil funding controlling for differences in costs of educating certain students. (Return to story)

;)