7 Ways 5,000 Districts & Charter Networks Are Spending Relief Funds on Teachers

Jordan & DiMarco: Trends in federal COVID ed aid spending: teacher hiring & retention, smaller classes, stipends, professional development & more

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This analysis is adapted from a new FutureEd report, “Educators and ESSER: How Pandemic Spending is Reshaping the Teaching Profession.”

In rural enclaves and city centers, in red states and blue, school districts share the same top priority for federal COVID relief aid: spending on teachers and other staff who can help students recover from the pandemic, academically and emotionally. Local education agencies are on pace to spend as much as $20 billion on instructional staff under the American Rescue Plan. In many places, the federal support comes on top of substantial state and local teacher investments.

To understand state and local policymakers’ strategies for bolstering teaching resources in the wake of the pandemic, FutureEd analyzed the COVID relief spending plans of 5,000 districts and charter organizations, representing 74% of the nation’s public school students. And we examined additional documents and conducted interviews to gauge how the nation’s 100 largest districts plan to reinforce their teaching ranks with the American Rescue Plan’s Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief fund (ESSER III).

The result is a comprehensive picture of state and local spending on the nation’s more than 3 million-member teaching force — including new hires, innovative ways to leverage top teachers, an emerging commitment to extra pay for longer hours and bonuses that break with traditional pay schedules to combat staff shortages. The challenges presented by the scale of the federal funding and the short window for spending it also emerged from the analysis.

We found seven significant spending trends.

1. Expanded Staff

While districts are investing heavily in interventions such as summer and afterschool programs and tutoring to address learning loss, especially for traditionally underserved students, a major priority has been adding instructional staff.

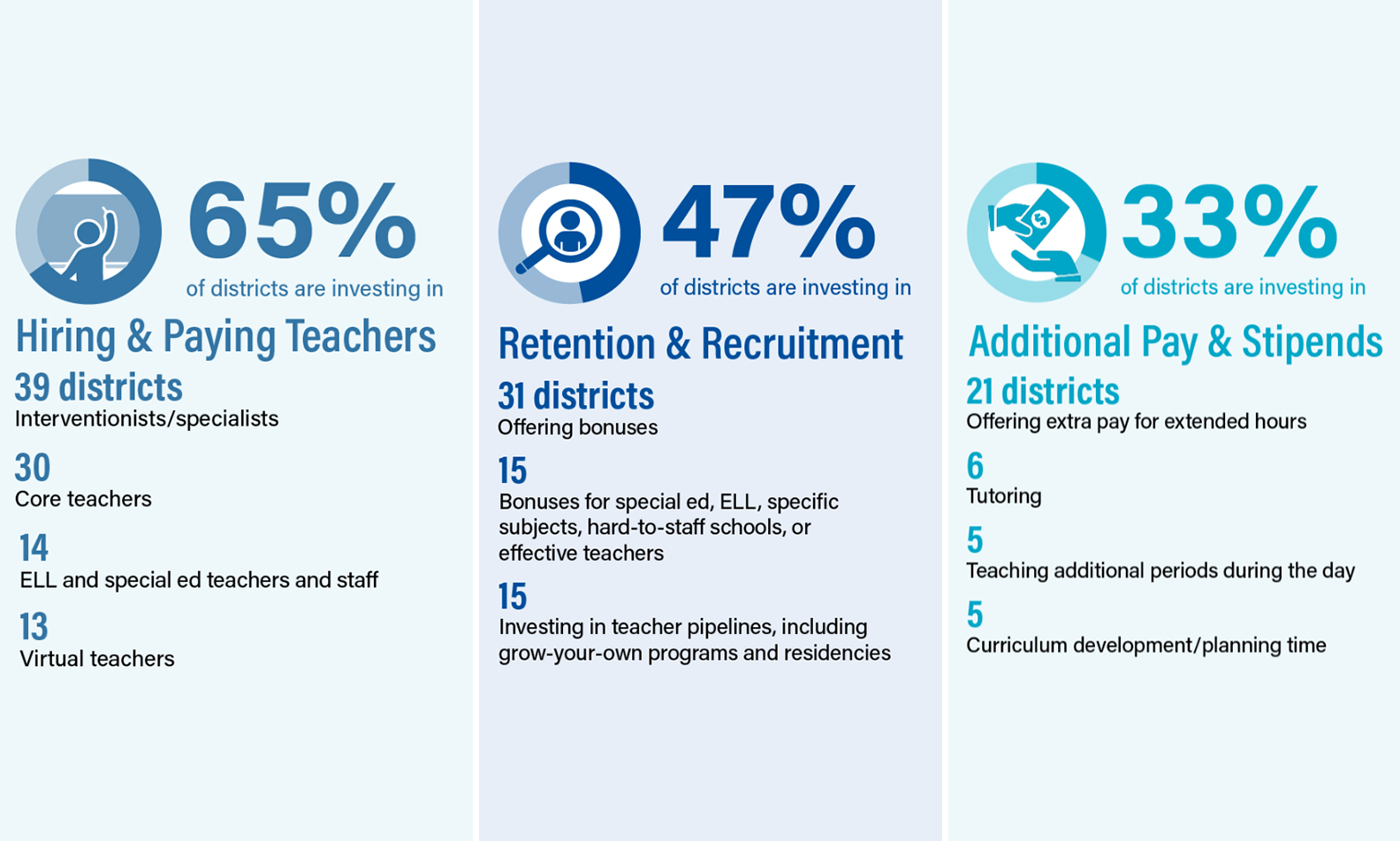

Our national analysis, using information compiled by the data services firm Burbio, found that about 60% of districts and charter organizations plan to use federal relief to hire new teachers or pay current staffers more to expand instruction. The plans include money for academic specialists who can coach students, typically in math or reading (mentioned by 39 of the 100 largest districts), as well as additional classroom teachers for smaller class sizes, and teachers or staff to carry out new or expanded initiatives. In most cases, these positions appear to be new hires, but some districts may be shifting existing staff into new roles and using federal dollars to pay them.

Some administrators are using money from their regular budget to cover these costs while shifting COVID relief aid to areas such as ventilation or technology more clearly tied to pandemic recovery.

Boston Public Schools expects to spend more than $10 million on 100 specialists, with schools determining what sort of academic support they need. Howard County, Maryland, is spending $1.1 million to cover three years of salary and benefits for resource teachers to focus on early childhood education and reading.

About 30 of the largest districts are using COVID relief aid to pay salaries and benefits for classroom teachers. Florida’s Manatee County Public Schools hired teachers using the earlier rounds of federal funding and are continuing those contracts with an additional $5 million. At least 13 districts — including Montgomery County, Maryland; Wake County, North Carolina; and Miami-Dade in Florida — are hiring or paying staff for new virtual academies.

Some new positions are explicitly described as short term: North Carolina’s Charlotte-Mecklenburg County School District, for instance, is using $5.8 million in federal money to hire about 400 “guest teachers,” essentially full-time substitutes with benefits, to cover for absent teachers or fill vacancies. The positions are set to expire when the funding does.

At least 15 large districts are using the federal aid to pay existing salaries, in many cases to avoid layoffs.

2. Smaller Classes

Reducing class sizes to provide more intensive support to students who fell behind during the pandemic is a common strategy among the 100 largest districts. Baltimore County, for instance, allocated $11.6 million over two years for 78 teachers to reduce class sizes. Several districts — New York City; Long Beach, California; Washoe County, Nevada; and Shelby County, Georgia, among them — focused these efforts on the primary grades.

Two Florida districts, Volusia County Schools and Lee County Schools, are taking a different tack by offering stipends to teachers who have larger classes. Their students could receive supplemental help through more individualized or small-group work.

Dayton, Ohio, has taken a novel — and more dramatic — approach to reducing student-teacher ratios, assigning one math and one literacy teacher to every classroom in grades 1 to 3 for two years. Each will work with half the class at a time. This required hiring 96 educators at a cost of about $10 million a year. The strategy has paid dividends: The district’s spring 2022 testing showed scores rebounding to 2019 levels and students showing faster academic growth than other students throughout the nation using the same test.

3. Recruitment

As districts returned to in-person instruction after months of virtual learning, many administrators realized they didn’t have enough staff members to fill their classrooms. In some places, teachers had moved to districts offering higher pay or left the profession. In others, there were simply new positions to fill. And in certain communities and academic specialties, teachers have always been hard to find. Little surprise, then, that about 20% of school districts in the national sample — and 47% of the largest districts — are using federal money to recruit and retain teachers.

Duval County, Florida, is using the federal aid to hire recruitment specialists and support their efforts. The Charleston, South Carolina, district is engaging university partners to attract and train new teachers and provide mentoring. Houston is waiving the $6,000 fee for its alternative teacher certification program, aimed at college graduates who haven’t majored in education and adults working in other careers.

At least 15 districts are developing teacher pipelines, work that complements what states are doing with their federal funds. Georgia, Kansas, Kentucky and Tennessee, among others, are investing in “grow-your-own” programs that recruit from among teacher aides, school support staff and local college students, a strategy designed to increase diversity and improve retention rates, especially in hard-to-staff schools. The Nevada Department of Education is using $20.7 million to provide tuition assistance and stipends to student teachers working in the state.

Several districts are offering recruitment or signing bonuses to draw teachers to hard-to-fill specialties, a practice that began before the pandemic. In Detroit, where 80% of teacher vacancies are in special education, the district is offering recurring $15,000 bonuses for qualified instructors.

4. Staff Retention

Since the pandemic began, some state legislatures have approved substantial salary increases to help districts hold on to the teachers they’ve got. Others are providing one-time bonuses or “hazard pay” for teachers and others.

Altogether, about one in 10 districts nationwide is paying retention bonuses to teachers and staff, our analysis suggests, a figure that has likely increased in recent months as districts continue to struggle to fill vacancies. At least 31 of the 100 largest districts are providing some sort of bonus to teachers. Wake County Schools in North Carolina, for instance, has pledged $49 million for bonuses and has already distributed nearly 60% of it, according to the state’s spending portal.

Houston Independent School District has offered $5,000 bonuses to teachers who agree to stay on the payroll for at least three years. Payments are spread out: $500 in June 2022, $1,500 in June 2023 and $3,000 in June 2024. The district also called upon a more traditional method: an across-the-board pay hike. Some $52 million in federal funding will essentially giving teachers an 11% raise up front.

Pay scales need to rise in many school districts. Teachers earned an estimated average of just $66,397 in the 2021-22 school year, while the Economic Policy Institute recently reported that teachers’ average weekly inflation-adjusted pay has increased by just $29 since 1996, compared with $445 per week for other college graduates. In recent years, several governors have devoted state dollars to hikes in teachers pay, influenced in part by the Red-for-Ed rallies that teachers staged at many statehouses just before the pandemic began.

Even so, targeting increases to critical shortages areas like math, science and special education are likely to pay the largest pandemic-recovery dividends, without setting the stage for layoffs once federal COVID relief aid ends.

5. Increased Workloads

At least 33 of the top 100 districts are earmarking federal money to pay teachers stipends for additional hours, a significant trend given unions’ traditional commitment to restricting the scope of teachers’ work. At least 21 of the largest districts are using federal money to pay teachers for working with students before or after school; another two are paying for work on weekends and during school breaks.

Six districts are paying teachers to tutor students, and five are paying educators to develop curricula. Miami-Dade County Public Schools, for instance, set aside $32.7 million for teachers to work an extra period a day for two years. Florida’s Duval County Public Schools is earmarking $349,000 to buy out planning periods for secondary school instructors, so they can teach an extra one or two classes.

Still, some efforts to increase learning time have met with resistance. The Los Angeles Unified School District, for instance, budgeted $122 million for three extra days of professional development and four additional days of learning for students this school year. Though voluntary, United Teachers Los Angeles voted to boycott the first of the learning days, planned for late October, and filed an unfair labor practice complaint, saying the extra days were not properly negotiated. Since then, a tentative deal would allow the extra days to continue but would cut four days off the end of the school. Negotiations are ongoing.

6. Improved Working Conditions

The pandemic has left many teachers stressed out and stretched thin. In response, some districts are using federal aid to improve working conditions, particularly allowing more time for planning and collaboration.

Houston is spending federal funds to move teachers in 18 schools toward a new approach to school management known as Opportunity Culture. Educators will receive $15,000 stipends annually to serve as classroom leaders across a grade level or subject. They’ll teach part time while managing teams of teachers, paraprofessionals and instructors in teacher residency programs to analyze student data, adjust instruction and develop their skills. The stipends are part of Houston’s regular budget, but federal funding is being used to expedite training and implementation.

The Orange County, Florida, school district is hiring additional algebra and high school English teachers at its five highest-need schools as part of a pilot initiative to reduce the teaching load and allow for more planning periods. The new model — four teaching periods and three planning periods — will provide additional preparation time and small-group instruction.

Philadelphia is using its COVID relief money to give teachers 120 minutes a week to coordinate planning with colleagues teaching the same grade. The goal is to discuss how to approach new units of study, review data, and share successes and failures. The district has posted a series of videos showing how teaching teams should discuss goals and break down new instructional units.

7. New Skills, Knowledge

Professional development has emerged as one of the most popular uses of federal COVID aid nationally, with about 43% of districts and charters nationwide planning investments and about 15% spending on social-emotional training and materials. Among the 100 largest districts, 82 plan to use the funds to train teachers on such topics as evidence-based instructional approaches, family engagement strategies and new technology platforms. Some are using the money to contract with training providers, while others are training their teachers to coach fellow staff.

At least 35 of the largest districts are putting the money toward literacy training, including a significant focus on evidence-based practices associated with the “science of reading.” The Utah’s Alpine School District earmarked $6.8 million to put teachers through a literacy-instruction training program known as Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling, or LETRS. Another large Utah district, Jordan, is investing $5 million in the same program, which emphasizes evidence-based practices including structured phonics instruction. The training is intensive and costly, taking more than two years to complete, but is one of more widely used approaches to improving literacy instruction.

With 25 states now requiring educators to undergo professional development in evidence-based reading instruction, the one-time infusion of federal funds provides an unprecedented opportunity to build teacher skills in this area. In Texas, for instance, primary grade teachers must attend a state-provided reading academy by the end of the current school year, and districts across the state are using federal funds to cover associated costs. Katy Independent School District is paying stipends to teachers to complete the specialized training, and Garland Independent School District is investing funds to expand reading academies through eighth grade.

In addition, as many as 36 districts plan to train teachers and staff on social-emotional learning and best practices for responding to the increase in student behavioral and mental health challenges. Places such as Maryland’s Howard County Public Schools are equipping teachers and staff with tools to recognize and address early signs of trauma and mental health issues. Omaha Public Schools plans to provide trauma-informed care training, which includes recognizing symptoms of traumatic stress and increasing awareness of its effects on the brain and body.

Other districts are providing training opportunities for culturally responsive teaching methods, restorative practices and conscious discipline, and implicit-bias training. Long Beach, California, for example, plans to use a portion of its allotment to provide training for a districtwide restorative-justice initiative, equipping teachers with conflict-resolution strategies, cultural awareness, positive behavior supports and other alternatives to suspension and expulsion.

Given the one-time nature of the ESSER funds and the looming fiscal cliff, spending on professional development can be a more sustainable approach to support and improve the teacher workforce, ultimately helping to address learning loss. But like any approach, professional development is not always effective

School districts have at least two more years to use their ESSER III money, and billions more dollars to invest. Momentum has been building behind several significant spending strategies: breaking with the traditional pay scale in response to shortages, deploying teachers in new ways to maximize talent, doubling down on the science of literacy, and equipping educators with skills and knowledge to support students’ mental health, a need that long predated the trauma many students experienced during the pandemic. These and other trends may result in long-term improvements in the teaching profession—and public education.

Yet, some investments could be difficult to achieve and hard to sustain. Determining which interventions have worked the best — which COVID relief bets to double down on — will be a key task of education policymaking at all levels in the years ahead.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)