3 Ways to Promote the School and Work Friendships that Foster Student Success

Manno: There’s no replacement for the education system’s important face-to-face role in nurturing cross-class and professional connections

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Young people are returning to schools and colleges after pandemic lockdowns suspended the education system’s important face-to-face role in nurturing personal friendships and professional connections.

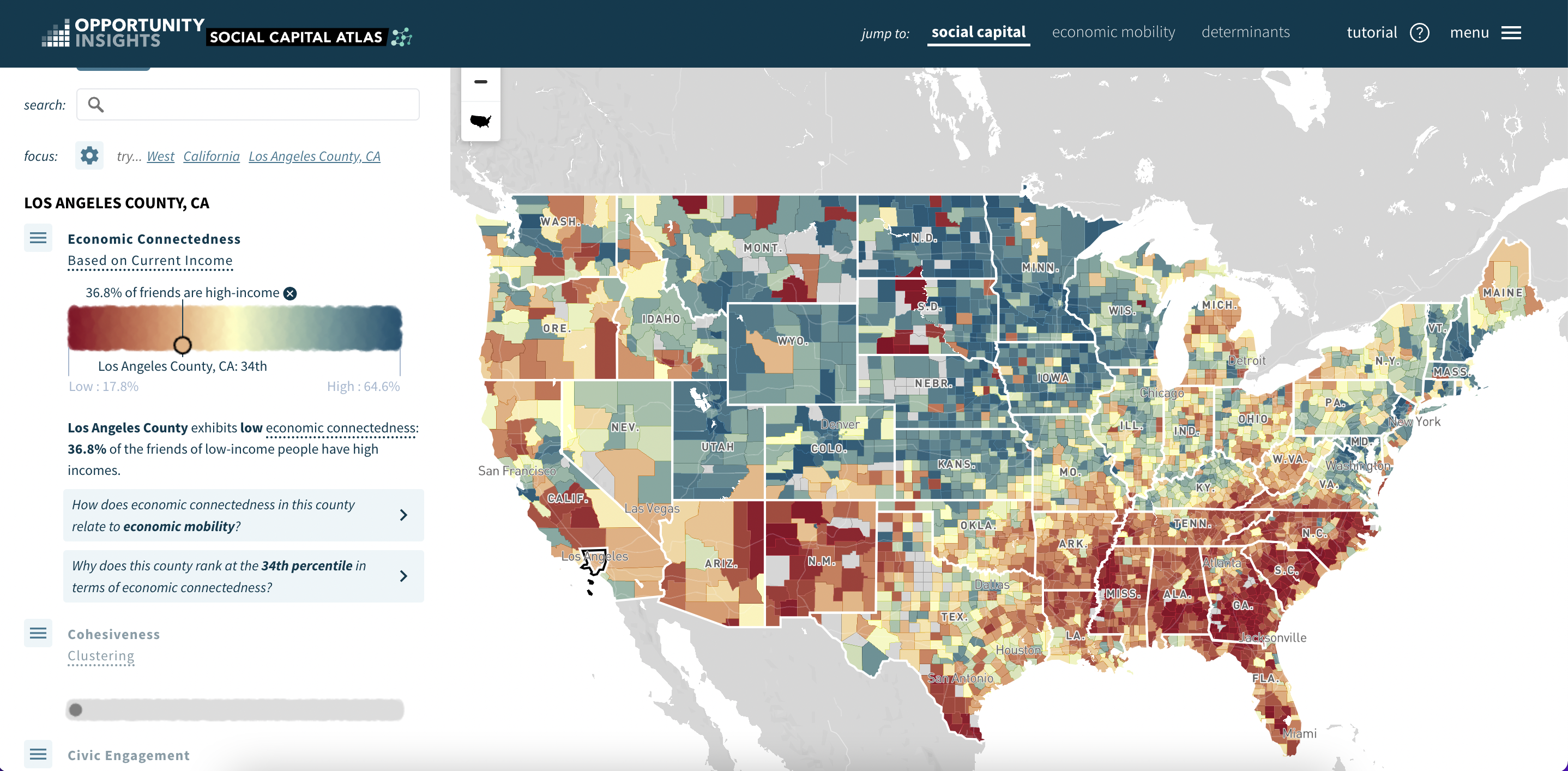

Recent studies by Harvard economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues show that friendships and other relationships across socioeconomic lines experienced in places like schools and the workforce play a key role in boosting upward mobility and expanding opportunity in America.

These community-level relationships, what the researchers call social capital, produce economic connectedness, which contrasts with friending bias, or people’s tendency to stay within the social class networks they know, associating with people like themselves.

The analysis is based on 72.2 million U.S. Facebook users, representing 84% of U.S. adults, ages 25 to 44, with 21 billion friendships. It includes a website where entering a zip code, high school or college shows the degree these cross-class friendships exist in communities and schools across the country.

Economic connectedness is among the strongest predictors of upward income mobility, stronger than measures like school quality, job availability, family structure or a community’s racial makeup.

For example, low-income children growing up in a neighborhood where 70% of their friends are wealthy increase their future incomes on average by 20%, similar to the effect of attending two or so years of college.

These cross-class friendships are important because of their downstream effect: Through them, individuals acquire new information about things like careers and educational options, learn how to interact with new people in different settings and have other experiences that shape their aspirations and behaviors, which have a multiplier effect over time.

These friendships vary across schools, even within neighboring schools with similar socioeconomic makeups. Large high schools have fewer cross-class and more income-related groupings. So do schools with high Advanced Placement enrollment and gifted-and-talented classes.

Conversely, smaller schools generally have less friending bias, or more social interaction between students from different backgrounds. Finally, colleges with greater racial diversity and larger student enrollments generally have more friending bias, or fewer cross-class friendships.

There are ways to reduce friending bias and increase social interactions or cross-class friendships between students. Here are three examples.

The first is from Chetty and his colleagues, who cite large high schools with diverse student bodies that assigned students to smaller, more diverse houses or groups.

The second comes from my colleague Jeff Dean, who analyzed the 214 charter high schools found in the study’s public database who have friending bias scores. He found that, on average, charter schools perform better than 80% of traditional public schools on friending bias, raising questions for further research. For example, do the autonomy and community-building aspects of charter schools contribute to this? If so, are there lessons learned that district schools could emulate? Should charter school growth limits be lifted so more of these schools can be created?

The third suggestion is inspired by comments Chetty and his colleagues make about creating new or expanding existing programs that promote cross-class interactions. I believe another promising way to promote cross-class friendships is by expanding career pathways education and training programs. These acquaint learners with employers and workforce demands, engaging students and adult mentors from diverse classes and backgrounds. This creates new social networks and information sources that can shape a young person’s downstream expectations and aspirations.

These programs weave together education, training, employment, support services and job placement. They include a wide range of models: apprenticeships and internships; career and technical education; dual enrollment in high school and college; career academies; boot camps for acquiring specific knowledge or skills; and staffing, placement and other support services for job seekers.

There are state-level partnership programs in places as politically diverse as California, Delaware, Colorado, Tennessee, Texas and Indiana. Other partnerships are local and feature collaborations among K-12 schools, employers and civic partners like 3-D Education in Atlanta; YouthForce NOLA in New Orleans; Washington, D.C.’s CityWorks DC; Cristo Rey, a network of 38 Catholic high schools in 24 states; and Wiseburn School District and Da Vinci Charter School in Los Angeles County, awarding associate or bachelor’s degrees through UCLA Extension and El Camino College or College for America.

Support is provided to those creating new programs by national organizations like the Pathways to Prosperity Network, P-Tech Schools and the Linked Learning Alliance.

These diverse programs have five common features: an academic curriculum linked with labor market needs leading to a recognized credential and decent income; career exposure and work, including engagement with and supervision by adults; advisers helping participants make informed choices, ensuring they complete the program; a written civic compact among employers, trade associations and community partners; and supportive local, state and federal policies that make these programs possible.

These initiatives are different from the old high school vocational education that tracked students into occupations based on family backgrounds and other demographic characteristics. They foster opportunity pluralism by offering individuals many pathways to work, career and successful lives.

The pathways approach helps students develop a practical sense of what it means to work in a specific job — an occupational identity — and a more general sense of their values, personalities and abilities, or vocational self. It also can yield faster and cheaper routes to jobs and careers.

The bottom line is that there’s no replacement for the education system’s important face-to-face role in nurturing cross-class friendships and professional connections.

That’s a welcome back-to-school message.

Disclosure: Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)