A Legal Right to Literacy: 10 Kids Sued California for Failing to Teach Them to Read. Could Their Settlement Set a Precedent for Other Struggling Schools?

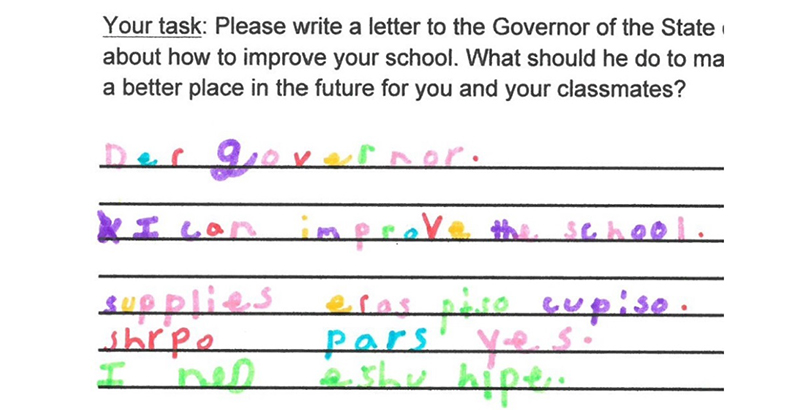

As a second-grader, a Los Angeles girl identified as Ella T. wrote to the governor of California asking for help for her school, LaSalle Elementary. Carefully and neatly written with a rainbow array of markers, it’s unintelligible.

“Der Governor,” reads the letter, now an exhibit in Ella T. v. California, a suit filed on behalf of the girl and nine other Southern California children. “I can improve the school. supplies eras piso cupiso. shrpo pars yes. I ned eshu hlpe.”

With only eight of LaSalle’s 430 students passing state reading exams in 2017, the year the lawsuit was filed, teachers — some of them also plaintiffs in the suit — knew they were failing but lacked the resources to intervene.

Now, Ella T. has had her day in court, winning a novel settlement with state education officials aimed at dramatically improving the strategies California’s lowest-performing schools use to teach reading. The suit was the first to argue that a state constitution guarantees a right to literacy, a skill that is fundamental to a person’s ability to participate in a democracy.

With 53 percent of the state’s third-graders not reading at grade level, California education officials say they will set aside $53 million to provide grants to bolster literacy at 75 of the state’s lowest-performing elementary schools.

LaSalle will be one of the schools eligible to apply for money and expert support in creating a plan to begin using evidence-based strategies to boost literacy and reduce discipline issues. The three-year grants must be used to fund new, proven practices, not supplement existing efforts.

“I am frankly most excited about the precedent it sets, that we acknowledge literacy and the gross inequities in achieving it,” said Pedro Noguera, founder of UCLA’s Center for the Transformation of Schools and one of the experts consulted by the plaintiffs. “The fact that the state was willing to settle was important — they acknowledge it is their responsibility.”

Requests for comment from the California Department of Education were referred to the governor’s office, which did not respond to The 74’s messages.

Plaintiffs attorney Mark Rosenbaum, of the pro bono firm Public Counsel, filed a federal lawsuit in 2017 charging that illiteracy in Detroit violated the U.S. Constitution. The suit’s dismissal a year later was not entirely unexpected, as courts have repeatedly decided that the federal Constitution does not guarantee children an adequate education. That suit is on appeal.

All 50 state constitutions, however, do establish a right to education. Recent years have seen numerous suits filed throughout the country arguing that states deny their students an adequate education in a variety of ways. For example, a current Minnesota case argues that ongoing segregation violates students’ right to a good education. In January, a North Carolina court ordered state officials to dramatically increase school funding in coming years. And a suit alleging that tenure laws deprive impoverished schools of a fair share of teaching talent is proceeding in New York.

In contrast, California’s is the first state case to argue that literacy is fundamental to participation in a democracy, the rationale cited in many state constitutions for the need for public education in the first place.

“Public schools in America were conceived as the engine of democracy, the great equalizer that affords all children the opportunity to define their destinies, lift themselves up and better their circumstances,” the 2017 complaint reads. “An education that does not provide access to literacy cannot be called an education at all.”

States that know that their schools fail to provide this access have an obligation to act, said Erik Olson, an attorney with the firm Morrison & Foerster, which partnered with Public Counsel to bring the case. “The state has a responsibility to pay attention to school-level data,” he said. “It’s really about the critical nature of literacy to success in our society.”

California, the Ella T. complaint argues, was well aware of both the fundamental role reading plays in ensuring a decent education and the illiteracy crisis in many of its schools. Acknowledging a “sense of urgency in implementing a state literacy plan,” in 2012 California convened a panel of experts who made pointed recommendations about changes needed to help schools teach disadvantaged children to read.

Black and Latino students, English learners, children with disabilities and those living in poverty were especially likely to attend schools where a handful of students, at best, passed state reading tests. Indeed, Stockton, one of the cities where the student plaintiffs’ schools are located, is the third-lowest-performing large district in the nation, the complaint notes, achieving only slightly better than Detroit.

The 2012 plan called for “a comprehensive, systemwide, sustained approach to intense reading instruction and intervention that is based on students’ diagnosed needs and current and confirmed research.” It was not implemented, the complaint charges, detailing ineffective steps teachers in Ella T.’s school took to try to compensate, such as having fifth-graders attend kindergarten for portions of the school day.

Because students must read to engage with any academic subject — something it’s generally believed must happen by third grade — the problem compounds as they grow up, foreclosing college and economic opportunity, plaintiffs noted.

The legal history of literacy is significant. Following the Civil War, Congress insisted that to re-enter the Union, former Confederate states had to extend the vote and bolster their public education systems, which were mostly off-limits to blacks. So Southern states amended their constitutions to recognize education as a right — and one necessary for participation in democracy. Northern and new states followed suit.

Research done by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, whose leaders recently proposed amending the Minnesota Constitution to strengthen its education clause, surveyed the language states use to describe the education guaranteed, as well as the frequency with which the clauses have been amended over time.

Despite Congress’s recognition of the relationship between literacy and an informed electorate, the U.S. Constitution does not mention schools or education. The 14th Amendment, also passed during the Reconstruction era, extended “equal protection of the laws” to all — the constitutional provision that led to the landmark school integration decision Brown v. Board of Education. In their Detroit case, the pro bono lawyers who won the California settlement argued that inequitable access to literacy also violates this right.

Many of the most visible, successful education lawsuits relying on state constitutions, however, have focused on funding — whether it is adequate and equitably distributed. Often, when courts agree with plaintiffs, they stop short of specifying how much money would be adequate or what it should be spent on.

And although lawmakers require education officials to set standards, state departments of education frequently lack mechanisms — or political backing — for seeing that those standards are met.

California education officials have been poorly positioned to help schools and districts identify strategies that have proved effective elsewhere with students struggling with differing challenges, said Noguera. “The state has limited capacity to help these schools,” having focused its energy on ensuring that districts comply with the law, he said. “It’s a journey to shift the way the states interact with schools.”

“Underperforming schools generally suffer from two problems: very high-needs kids and low-capacity staff,” he added. “We know that money alone doesn’t solve it. You have to use the money in ways that are most effective.”

To that end, the attorneys in the California suit tapped a roster of experts to help frame their case. In addition to Noguera, they relied on the University of Michigan’s Elizabeth Moje, an expert in critical literacy; Patricia Gándara, co-director of UCLA’s Civil Rights Project; Maisha Winn, co-founder of the University of California, Davis’s Transformative Justice in Education Center; and others.

And they considered the strategies called for under the state’s 2012 literacy plan. Schools that want one of the grants must conduct a root-cause analysis to identify factors, including school climate, that impede learning, as well as solicit community feedback. Next, in conjunction with outside experts, they must develop a plan that includes things like literacy coaches for teachers, culturally responsive curriculum and the use of data to monitor reading strategies.

Funding for the settlement will have to be approved by the California Legislature, with initial grants of $50,000 per interested school to be disbursed in the fall to pay for the root-cause assessments.

It was important to the plaintiffs’ attorneys that each school seeking a grant be allowed to craft its own solution and that the potential strategies have the best possible chance of success. “Seventy-five applications gives you 75 approaches to the problem,” said Olson. “The hope would be every one works. But the practical reality is that probably won’t happen.”

The settlement leaves open the door for an evaluation of which strategy combinations worked in different school settings, though since the state was unwilling to pay for this assessment, funds would have to be raised.

Noguera said he hopes the results of grants will be monitored in an effort to identify strategies that can work in other struggling California schools. “It will be interesting to look at which schools will be able to make gains,” he said. “What about the conditions at those schools allowed them to make those gains?

“Changing outcomes on something like literacy is going to take a lot of effort.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)