Ohio Judge Rules State’s $700 Million Voucher Program Is Unconstitutional

School choice backers vow appeals after Ohio private school tuition vouchers for 140,000 students are found to shortchange school districts.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

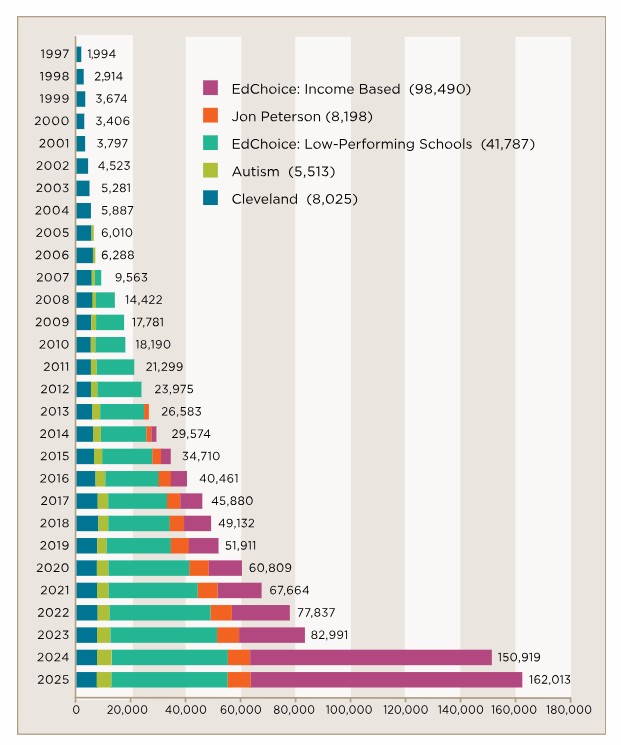

An Ohio judge has found the state’s main voucher program violates the state constitution, dealing a blow to one of the nation’s largest private school tuition payment programs and one that has grown dramatically the last several years.

Whether that ruling — from a Democratic judge in a county-level court — survives appeals to the Republican-dominated Ohio Supreme Court will be the real test.

If it stands, the ruling would cut off the $700 million Ohio now pays for 140,000 students to attend private, mostly religious schools, through its EdChoice voucher program. Voucher opponents, who say EdChoice takes away money from school districts, hope the money will now go to public instead of private schools.

EdChoice makes up nearly 90% of Ohio’s voucher programs by giving students and schools nearly $6,200 a year each through eighth grade and $8,400 for high school.

In a late June ruling, Franklin County Common Pleas Judge Jaiza Page found that EdChoice, once a small program limited to only low-income students or those at schools with low test scores, has expanded so much after Ohio opened it up to any student in 2023 that it violates parts of Ohio’s constitution calling for the state to fund “a system of common schools.”

In the EdChoice case, filed by school districts against the state in 2022, Page agreed that the vouchers, which are used mostly at religious schools that can choose who they accept and what they teach, have created a second, parallel school system that’s selective, not common.

“In expanding the EdChoice program to its current form, the General Assembly has created a system of uncommon private schools by directly providing private schools with over $700 million in funding,” she wrote.

Page, though, recognized that EdChoice has grown so fast that ending it would cause “significant change to school funding in Ohio.” She held off ordering EdChoice to shut down until after appeals, even as she ruled against it.

Yitz Frank, a suburban Cleveland rabbi and president of School Choice Ohio, vowed to appeal Page’s ruling. He praised her, though, for delaying ending the vouchers just a few months before the start of a new school year.

“You would essentially have well over 100,000 students lose their scholarships,” Frank said. “Tens of thousands of them would have no ability to even figure out how to possibly make those tuition payments. I’m sure there are some more middle class families that might be able to figure it out with great sacrifice, but it would be pretty devastating for the families.”

The ruling, if upheld, is high stakes for Ohio, but will have little impact on vouchers in other states because it centers on language in the state constitution and falls under state courts.

It’s the latest, however, in a string of state court findings against state aid for private school tuition, including in Utah and Kentucky, where a bid to change the state constitution to allow state money to pay for private schools also failed.

The case is also significant because Ohio’s voucher program is among the largest in the country. Ohio spends the fourth-most of any state on private school tuition assistance, relative to total state spending on education, according to EdChoice, the nonprofit school choice advocacy group.

Florida leads the way, with just over 10% of state spending on education going to private school tuition through vouchers, tax credits or related Education Savings Accounts. Arizona is close behind at 7% and Wisconsin at 5% before Ohio and Indiana follow at around 3.7%.

Voucher opponents, though, hope EdChoice clears appeals and ends soon. They disagreed that cutting off vouchers would be so harmful to families, noting that many sent their children to private schools without vouchers until the Republican majority in the legislature lifted income limits over the last few years.

“Taxpayers are being ripped off,” said Dan Heinz, a school board member of the Cleveland Heights-University Heights school district, the district historically most affected by EdChoice. “Wealthy families that have always used private schools and afforded private schools are now having that tuition subsidized by much poorer families.”

Smaller Ohio voucher programs, including two for students with disabilities and one only for Cleveland residents, are not part of the case. The Cleveland program is well-known as the center of the 2002 U.S. Supreme Court case Zelman v. Simmons-Harris that allowed vouchers to be used for students to attend religious schools.

Page also ruled that Ohio’s requirement for “common schools” means that public schools, the “common” ones, should be fully funded. She agreed with districts that the state legislature has not met that mandate, particularly by under-funding the planned phase-in of the “Fair School Funding” formula it passed in 2021.

“The state provides hundreds of millions of dollars in funding to private schools through EdChoice while at the same time Plaintiffs are unable to educate their students because the General Assembly decided not to fully fund public schools,” Page wrote.

Voucher advocates promise to appeal, saying they are not surprised by this ruling by a Democratic judge in one one the most Democratic-leaning counties in Ohio, even as the state has trended strongly Republican in recent years.

Advocates including Keith Neely, a lawyer for the Virginia-based Institute for Justice who helped defend EdChoice on behalf of families using the vouchers, said he expects to easily win at the Supreme Court for a few reasons, including that Ohio has no ban on funding additional schools if the state also pays for a “system of common schools.”

“There’s no provision… that prohibits the general assembly from enacting scholarships, or even providing for this other system of uncommon schools,” he said. “I think plaintiffs are wrong to try and argue that there is a restriction in Ohio’s constitution that prevents the state from providing for educational alternatives like Ed choice.”

Voucher opponents, who say they now have half of Ohio’s 611 school districts, including large ones, as plaintiffs in the case, praised the ruling and hope that public pressure will overcome the political leaning of the state Supreme Court. Six of the seven members, all of whom face election, are Republican.

“Put on the political lens for these people (justices) when they’re looking at 75% of the state’s voters living in districts that have signed up for the lawsuit,” said Heinz. ”That’s not a very promising outlook for their political futures.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)