Explosive Growth for Ohio’s School Vouchers, as 50% More Students Applied to Program in 2023

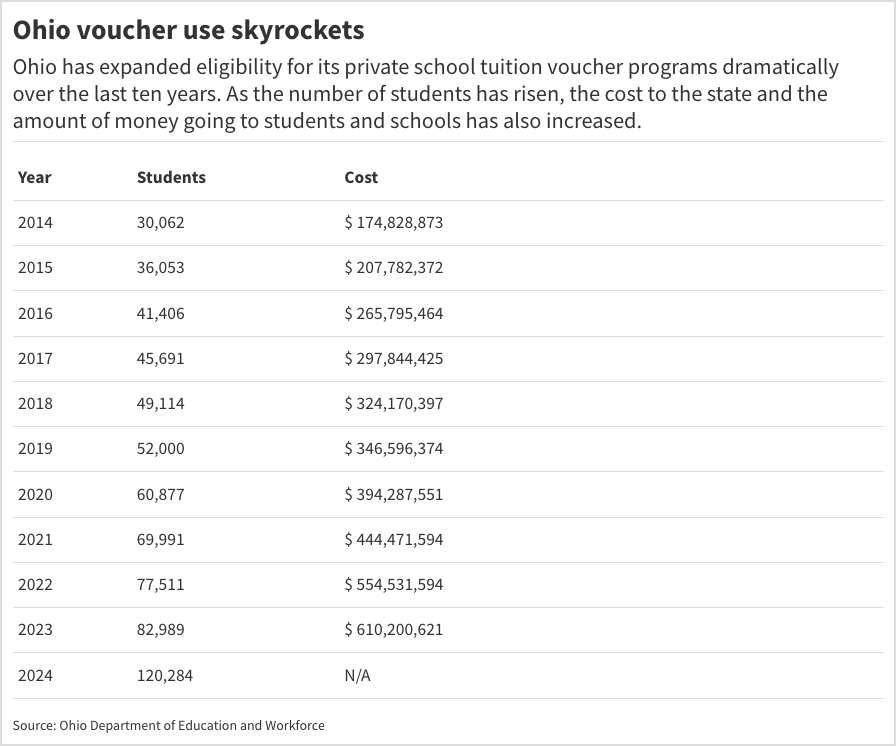

Vouchers have grown 400% over 10 years, from 30,000 students in 2013 to more than 120,000 today. Lawmakers expect further expansion next school year.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The massive growth of Ohio’s controversial tuition voucher programs has been a lifeline for schools like St. Anthony of Padua elementary school in Akron, which once had such low enrollment it had to merge with another struggling school.

St. Anthony would have closed if Ohio’s legislature had not made vouchers so available over the last 10 years — so much so that the school can fill its 225 seats with students using vouchers to pay tuition they couldn’t afford otherwise, said Scott Embacher, a consultant for the school.

Without the vouchers “it would be stunning if we were still open,” he said.

Private schools across Ohio like St. Anthony have seen an infusion of hundreds of millions of tax dollars in recent years as the Republican-dominated state legislature has made vouchers available to more and more families. After years of enrollment declines and closures, private school operators, particularly religious schools, are filling seats, adding students and even looking to expand.

Voucher use in Ohio has grown more than 400 percent in the last 10 years, from 30,000 students in 2013-14 to more than 120,000 today. The state tax dollars going to families and private schools has grown from $175 million then to potentially $1 billion a year now.

The most dramatic leap — a nearly 50 percent jump from 83,000 to 120,000 — came just this school year after the Ohio legislature eliminated the last income cap for families to receive a voucher in summer of 2023.

Ohio Senate President Matt Huffman, the legislature’s leading champion of vouchers, said he expects that number to climb again in the 2024-25 school year. Because the eligibility rules were changed so late, families and schools had little time to learn of the changes and make plans for the fall.

“People have already made their decisions for the year about where their child is going to go,” he said. “They’re going out for the basketball team, and they’ve already got the bus route . So the increase in the number of new students next year, it’s going to be much greater, because people will have figured it out.”

Huffman said he hopes the latest increase in vouchers will help older schools build up enrollment and even add new classrooms. He has hinted at directing more money to them, but has not proposed any plan yet.

If he does, Ohio’s bitter debates over vouchers that started when it was one of the pioneering states in the movement will flare up again.

Ohio’s Cleveland-only voucher program in the 1990s was one of the first in the country and sparked complaints that it improperly advanced religion by providing tax money for religious schools. The landmark Zelman vs. Simons-Harris Supreme Court ruling in 2002, which sprung out of the Cleveland vouchers, allowed religious schools to be part of voucher programs if they were not the only recipients.

Since then, often led by Huffman, Ohio has added vouchers for low-income students, for those whose local public schools were designated as “failing” because of low test scores and then for families with ever-increasing incomes, raised in steps over time. Most recently, the legislature in 2023 removed the last income limit for voucher eligibility.

Every student is now eligible for $6,165 through eighth grade and $8,407 for high school, with a sliding scale of reductions only when family income is over 450 percent of the poverty level, or $135,000 for a family of four. Even then, voucher amounts can never go below 10 percent of the standard amount.

At each step voucher expansion drew applause from school choice advocates, while also sparking complaints from school districts and teachers unions that they pulled students and dollars out of district schools. Criticism of funneling money to religious schools has continued, as several estimates show more than 95 percent of voucher dollars in Ohio go to those religious schools.

A coalition of school districts have sued the state to block voucher expansion for these reasons since 2022. A trial is scheduled for November.

State aid to private schools could grow in yet another way. Some school choice advocates, including the conservative Buckeye Institute, have started calling for the state to start paying for private school construction, as it does with public schools. Brian Hickey, executive director of the Ohio Catholic Conference, said schools would welcome help building schools in rural areas that don’t have existing Catholic schools.

St. Anthony is looking for money to build a four-classroom addition behind the school and has early drawings of how it would look while it seeks funding. The school is already asking legislators if there might be state money available.

The most recent voucher expansion passed in 2023 seems to be serving students already at private school in this first year, avoiding the usual complaints of taking students from traditional districts. But critics blast it as simply a transfer of money to middle- and upper-class families who had already been able to afford having their children in private school.

Criticism persists that Ohio’s voucher programs have less state accountability than traditional school districts or charter schools. There is no national consensus on how voucher students are tested and if schools should be rated.

Some states, like neighboring Indiana, have private school students using vouchers take all state tests. The state then gives those schools the same report cards as district and charter schools.

In Ohio, the legislature has slowly stripped away requirements for voucher students to take state tests and now have the voucher schools just report results of other national standardized tests of their own choosing, like the ACT or SAT.

That has long drawn criticism from opponents, who say that all schools using tax money should be held to the same standards.

“One thing that you won’t see in the (state) report cards is ratings for private schools that are now taking hundreds of millions of dollars in taxpayer funds, subsidizing private school tuition,” said Scott DiMauro, president of the Ohio Education Association, one of the state’s two large teachers union. “As voucher enrollment is exploding, I think there is a massive need for accountability.”

In response to these complaints, two Republican representatives introduced a bill last month calling for state report cards for private schools accepting vouchers and for those schools to report more financial and student disciplinary data.The bill has yet to have a hearing.

The conservative leaning Fordham Institute, which supports school choice and most of the voucher expansion, has publicly shared concerns about accountability. And while Chad Aldis, who leads Fordham in Ohio, said he’d probably support money helping private school construction, he’d want safeguards there too. As with charter schools, Aldis would want to be sure private school operators can’t build facilities or buy equipment with tax money and then use them for something other than a school.

Voucher supporters say adding testing and other reporting requirements would increase administrative work and costs. They say the schools are a bargain, costing the public far less than district schools with all their local taxes on top of state aid. And they say parents don’t need report cards to know if the school is right for their children.

Huffman said it’s not really fair for public schools to call for the same accountability for private schools because public school districts never close. Private schools have had to close after losing students, he said.

“They’re not held accountable,” Huffman said. “They in fact, continue to operate, especially schools that don’t perform academically. That’s not true for private schools, because parents take their kids out.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)