As Deportation Target Widens, College-Educated Undocumented Grow More Fearful

While Trump’s focus has fallen on immigrant laborers, there are 1.7M undocumented with a bachelor’s degree or higher and 408K enrolled in college.

Brian knew when he graduated from high school in 2013 that he couldn’t afford a bachelor’s on his own. Undocumented and unable to qualify for federal financial aid, he decided to enroll at community college and chip away at his associate degree a couple of classes at a time, using the money he earned as a deejay.

Brian came to the United States from Mexico when he was just 2 years old. He had no idea how he would pay for a four-year degree until he won a scholarship designed for students like him. A business management major, he graduated from Northeastern Illinois University in 2020 and now lives in Virginia, where he works in education policy and also owns several rental properties.

“I always pushed myself, but the biggest push of all came from my parents,” said Brian, a lawful permanent resident who asked to be identified by his first name only for fear he could be targeted for removal by the Trump administration. “They would ask us to pursue our education because that’s why they came here. They wanted us to make a better life than what they were able to.”

College graduates like Brian with temporary immigration statuses might not be the primary focus of President Donald Trump’s aggressive deportation effort, but they are no less alarmed by the forced removal of those with similar vulnerability.

Much of the nation’s attention has fallen on undocumented laborers — an Episcopal bishop pleaded with Trump at the National Prayer Service in January to show mercy to “the people who pick our crops and clean our office buildings, who labor in poultry farms and meatpacking plants, who wash the dishes after we eat in restaurants, and work the night shifts in hospitals” —but the administration’s deportation scope is widening and has grown to ensnare those on college campuses.

More than 1.7 million of the nation’s 11 million undocumented immigrants have earned at least a bachelor’s degree, according to a 2022 report from the Center for Migration Studies of New York. Ernesto Castañeda, director of the Center for Latin American and Latino Studies and the Immigration Lab at American University, said many people underestimate this group’s educational attainment.

Most don’t know some immigrants are more credentialed than Americans upon arrival, he said. For example, 48% of Venezuelan newcomers ages 25 or older reported having a bachelor’s degree or higher in 2023 compared to 36% of U.S.-born Americans, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Deporting this population would mean an enormous drain of “brain and brawn,” Castañeda said.

“If we expel those people, there would be a big economic loss — and a loss of decades of innovation and scientific discovery, as well as in arts and culture,” he said.

While Trump’s immigrant policies have been cited for making it more difficult to fill agricultural, construction and hospitality jobs, it will also shrink the nation’s pool of highly skilled workers, said Prerna Arora, associate professor of psychology and education at Columbia University’s Teachers College.

“Do we have the necessary workforce to complete the things that we need done, especially in a modernizing society?” she asked. “So many of these [college-educated, undocumented] people — and this is what happens across fields — want to go back and help communities from which they are a part.”

Higher education in the crosshairs

More than 408,000 undocumented students were enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities in 2023, representing 1.9% of all college students. The figure was higher pre-pandemic when it stood at 427,000 in 2019. The American Immigration Council attributes some of the decline to COVID and ongoing legal challenges to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the Obama-era program that gave temporary deportation relief to hundreds of thousands of immigrants brought to the U.S. as children, allowing them to study and work.

One Florida lawmaker now seeks to bar the undocumented from state colleges and universities entirely: they’ve already lost access to in-state tuition there. Texas is considering a similar measure.

Trump has made higher education a key focus of his immigration enforcement actions, targeting international students — many because of their political speech or protest actions around the war in Gaza. Thousands have lost their F-1 or J-1 student status as part of his crackdown, though the administration recently reversed those revocations in the face of court challenges.

Still, these international students’ future remains unclear. They are increasingly looking toward other countries as Trump continues to raid dorms, pull students off the street and place them in detention centers far from home.

Another academic, a 32-year-old woman from Senegal, who has lawful permanent resident status but asked that her name be withheld because she fears the current administration, called these removals heartbreaking and unjust.

“We should be investing and supporting young people, not criminalizing them,” said the woman, who came to the United States with her family at age 7.

She grew up in Harlem and scored high enough on the selective admissions exam to be accepted to Brooklyn Technical, one of New York City’s premier public high schools. A law and society major, she graduated from Brooklyn Tech in 2011.

It was an enormous accomplishment. Her father had no formal schooling in his home country and her mother attended only through the ninth grade. Their daughter has a master’s degree.

“My life and achievements are proof of what results when we make these investments,” she said. “So apart from the devastating impact these actions have on these young people’s lives, these actions harm communities — and all of us as a country.”

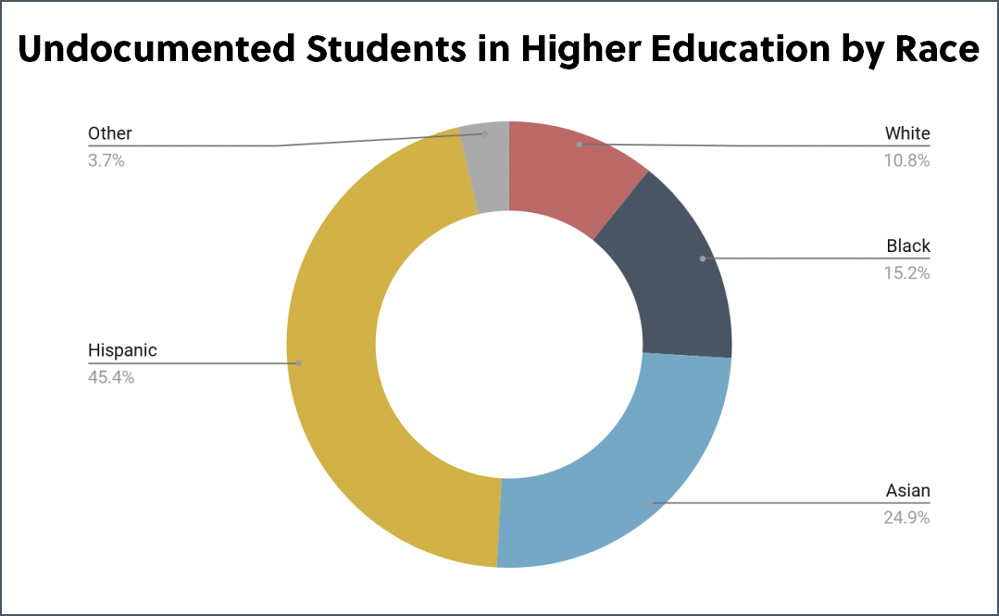

Roughly 88% of undocumented higher ed students are enrolled as undergraduates and 12% are in graduate or professional schools. Forty-five percent are Hispanic, 24.9% are Asian, 15.2% are Black and 10.8% are white, according to the Higher Ed Immigration Portal, which based its findings on data from a one-year sample of the 2022 American Community Survey.

California, Texas, Florida, New York and New Jersey make up the top five states with the most undocumented higher education students. More than 27% of undocumented graduate students nationally earned their undergraduate degree in a STEM field.

David Blancas, 37, got his bachelor’s degree in secondary education and mathematics at Illinois’ Aurora University in 2009 — he was a stellar student and won a scholarship that covered most of the cost — and worked as a math teacher in Chicago public schools for five years.

He got his master’s in urban education from National Louis University in Chicago in 2013 — also funded by grants and scholarships — and currently works in a leadership role at an organization that helps renters become homeowners through counseling and financial assistance.

Like Brian, Blancas, born in Mexico, came to the United States as a toddler. His father arrived in Chicago first to secure a job — as a busboy and then a cook — and an apartment before his wife and children joined him.

Blancas is the first in his family to graduate from college: His mother dropped out of school before eighth grade and his father stopped attending by ninth grade.

But they always prized education.

“They loved school,” Blancas said. “They constantly talked about how they were good at it and how they were very sad that they couldn’t continue because of financial reasons. To them, education was like the biggest thing.”

The Senegalese-born scholar said the same, despite the obstacles she faced: She wasn’t aware of her citizenship status until she was told that she needed a Social Security number to fill out the federal financial aid form for college and found out she didn’t have one. Thankfully, she said, she was accepted by DACA and went on to earn her bachelor’s degree in political science and economics from Hunter College in 2015.

She worked 35 hours a week in a retail store to cover her tuition and soon joined Teach for America, which recruits college graduates to serve in high-need schools. She paid for her master’s at the Relay Graduate School of Education out-of-pocket with her teaching salary. She eventually became an assistant principal and now works in policy and advocacy for a national nonprofit aimed at helping schools better serve all students — including immigrants.

Living that suburban American life

Local and state police around the country are assisting the Trump administration in its immigration enforcement and deportation push. Chicago, where Brian grew up, is a sanctuary city, one that has pledged by law not to cooperate in these efforts. The president has taken aim at these locations with Chicago its most prominent target: The Justice Department is suing the city and the state of Illinois for allegedly impeding its enforcement campaign.

As a boy and a young man, Brian wanted to be a part of the Chicago Police Department and spent hours watching Law & Order SVU to get a sense of that life. He applied for a job there as soon as he earned his associate degree.

“That’s when they told me they didn’t accept DACA recipients,” he said. “I was heartbroken. I did the physical, I did the mental exam and everything, and they did the vetting — they interviewed my neighbors and other people. It was a hard reality check. It was difficult for me to accept that.”

After the setback, he pushed on.

“It’s not just about me or my family,” said Brian, who also works in education policy with an eye toward immigrant students. “It’s for my entire community — to break that stigma that undocumented immigrants are uneducated or that we’re lazy or that we’re just mooching off of the system. People don’t know that for DACA, you have to go through a background check. You have to pay a fee, show that you’re working, you’re paying taxes, that you’re going to school.”

It’s frustrating to see people fighting to end the program, he said. Blancas, also allowed to work under DACA, agrees. He has a wife and two children and lives what he described as a typical middle-class life.

He said he understands America’s desire to protect its border, to ensure entry to only those who will add to the economy. But that’s exactly what they are getting from the very people they are trying to chase out, he argued.

“We have our own house,” Blancas said. “We both have really great jobs that give back to the community. We’re able to provide a great life for our children. We’re living that suburban American life, which is amazing.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)