When Graduating Isn’t Enough: New KIPP Scholarship Will Help First-Gen College Grads At Risk of Being ‘Underemployed’

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The KIPP charter school network’s announcement of another scholarship program designed to launch their alumni into successful careers — and avoid the underemployment problems of years past — represents the latest mile marker along a steep learning curve.

The nation’s largest group of K-12 charter schools said last week that the Ruth and Norman Rales Scholars Program will provide four years of mentoring, summer internship assistance, financial literacy training, networking advice and funding to defray college costs — supports valued at $60,000 per student. The grant covers 50 students a year, up to 250 students over five years.

For KIPP students such as Harlem-raised Airam Cruz, who landed a spot in a prestigious high school as a result of attending a KIPP middle school, and then entered Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, these networking-assist scholarships mean everything.

Cruz, who was chosen for a similar Dave Goldberg Scholarship Program (which inspired the Rales) got a summer internship at a computer gaming company as a result of meeting the company’s chief executive officer at a 2018 Silicon Valley dinner hosted at the house of Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg Goldberg is her late husband.

Also as part of that Goldberg scholarship program: Cruz, now 21, had his own mentor for four years of college, former Samsung Chief Innovation Officer David Eun. “I texted him almost any day about anything. Life advice, school advice.”

What’s truly newsworthy about the Goldberg and Rales scholarship programs is why they are needed in the first place.

Two decades ago, KIPP and other top-performing charter networks started out with a simple promise to parents: Send your sons and daughters to our schools and we will get them enrolled in college. As years passed, however, every charter network found out that enrolling in college wasn’t the same as graduating.

As early as 2009, KIPP leaders realized their college-going students were falling short on actually graduating, and in April 2011 released a starkly worded College Completion report revealing that only 33 percent of its KIPP middle school students were graduating from four-year colleges within six years.

While that rate was three times the national graduation rate for low-income, minority students, it was far below what KIPP had predicted: a graduation success rate of 75 percent. That was a wake-up call for KIPP, which launched aggressive changes including expanding its network to opening elementary and high schools to give students more time on task with KIPP teachers and counselors.

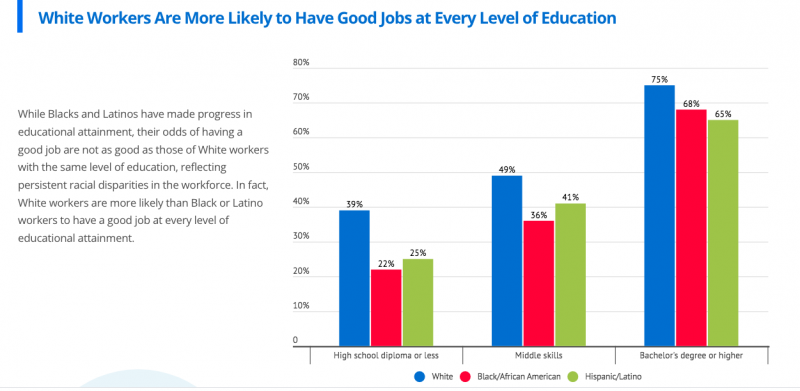

While those changes, and similar ones at other college-focused charter networks around the country, succeeded in boosting college graduation rates, KIPP and others soon discovered yet another unpleasant reality: simply earning a college degree wasn’t enough. Too often, their graduates settled for jobs that fell short of the kinds of professional opportunities landed by white and Asian college graduates.

That amounts to underemployment, explains Tevera Stith, senior director for National Alumni Impact at KIPP.

“We see more and more students not having access to proper networking who then struggle to get the kind of work experience needed to land the perfect first job that will propel their career,” said Stith For college students coming from middle- and upper-income families, those internships and first-job connections often come from family connections.

A 2016 survey of KIPP college graduates revealed that roughly half felt they were underemployed. The most common reason is having to pass on unpaid internships during their college years.

“When they can get a paid job at a local supermarket they are absolutely going to take that supermarket job,” said Stith.

Programs such as Rales offer students salaries for summer internships that don’t pay.

Underemployment is what I saw first hand when reporting the book, The B.A. Breakthrough, which documented the first graduating class at KIPP’s Gaston College Prep, a school in rural North Carolina located in a town where college graduation is not an expectation. But in this class, 61 percent of the graduating seniors earned four-year degrees within six years, a rate that exceeds the degree attainment rates for middle-class students.

While that success rate was impressive, it soon became clear that a fair number of those alumni didn’t consider themselves successes in life, at least not when compared to middle-class college graduates. While they were all employed, their jobs often fell into the category of underemployment, such as a finance major working as a bank teller.

These latest iterations in the learning curve around what it takes to get low-income minority students into college, through college and into a job commensurate with their skills, explains the multiple name changes for KIPP’s college promotion programs. It began in 1998 as Kipp To College, then in 2008 became KIPP Through College. In 2021 it became KIPP Forward, which acknowledges both the need to help students with non-college careers and that even college graduates need ongoing assistance.

Other charter networks make similar efforts. The New York City-based Success Academy schools, for example, have their own Rales Scholars Program.

The Northeast-based Uncommon Schools, which usually turns in the top college graduation rates, rivaling the success rates for middle-class students, also recognizes the need for follow-up support. Uncommon is building a network to link all its alums and connect them to outside organizations for career support.

Chicago-based Noble Network of Charter Schools offers one-on-one career counseling and networking events as well as employer programs like Noble’s Winter Externship Program.

Aide Acosta, Noble’s chief college officer, said a 2016 survey of their alums showed that six months after earning college degrees only 41 percent had full-time employment or were in graduate school. Compared to middle-class college graduates, she said, “our students were having different career exposures.” After launching Noble’s coaching/job placement efforts, that number is now up to 80 percent.

Some students get exposed to multiple programs. Kourtney Buckner, for example, attended a KIPP middle school in Atlanta. KIPP then helped her win acceptance at George Washington University. Buckner, a junior who plans on being a lawyer, has a KIPP college adviser who checks on her and the network helped her land a KIPP-supported summer internship at a Washington-based nonprofit.

At the same time, Buckner is also a Posse Foundation scholar, a program that ensures first-generation students find a network of similar students to support them in college. “Having a Posse cohort here has made all the difference,” said Buckner. “I have nine other (Posse scholars) here and I also have a Posse mentor.”

Applications for the Rales Scholars Program opened Oct. 1 to KIPP high school seniors or KIPP middle school alumni now in their senior year. The first group of Rales scholars will join the program in May 2022.

Disclosure: Walton Family Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York provide financial support to KIPP and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)