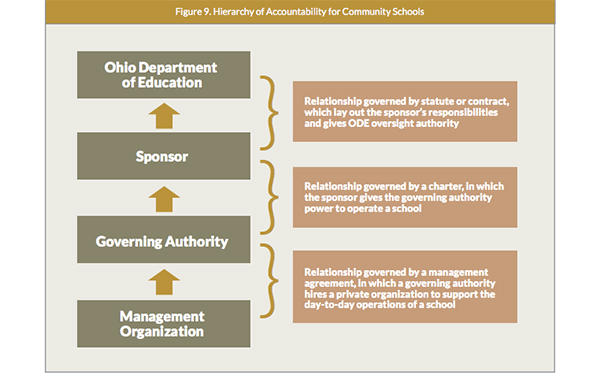

Added to this morass are the for-profit education management organizations that operate many Ohio charter schools. For-profits cannot sponsor charter schools, but governing boards can contract out day-to-day operation of the schools to for-profit — as well as nonprofit — companies.

Attempts to scrap bad charter management companies in Ohio can be stymied by a 2006 law allowing the companies to appeal closure decisions made by charter boards to more sympathetic authorizers.

Transparency in spending of public funds is remarkably limited.

In one bizarre case, the Ohio Supreme Court recently ruled that the for-profit company, White Hat Management, permanently owns physical school property — including computers and furniture — purchased to fulfill its contract to operate the school. As a dissenting judge wrote, “The contracts require that after the public pays to buy those materials for a public use, the public must then pay the companies if it wants to retain ownership of the materials.”

Attempts to make charters more accountable are often watered down to the point of being meaningless. For example, a law targeting dropout recovery charter schools — those specifically designed for students who have already dropped out of school at least once or are at high risk of dropping out — was essentially gutted by a provision that guaranteed that any school with a 10 percent improvement in certain metrics would be saved from any sanctions.

This seems reasonable, except that it refers to percent, not percentage points — meaning a school with a basement-level 5 percent graduation rate could be held harmless simply by increasing that rate to a barely better 6.1 percent in two years.

Policymakers have also struggled to regulate Ohio’s largely unsuccessful group of virtual charter schools.

“Even when quality controls were put in place, there were loopholes,” said Harris, the StudentsFirst director.

The latest setback to accountability garnered national attention when Dave Hansen — the Ohio Department of Education’s school choice director and husband to Gov. Kasich’s campaign manager — was forced to resign after omitting the failing grades of online charter schools from state report cards. His apparent reasoning was that the poor performance of online schools would “mask” the success of other charters.

Both Harris and Aldis in interviews with The Seventy Four disagreed with Hansen’s decision. But they gave him some credit, saying that under his leadership the department had made significant progress in holding charter schools and their authorizers more accountable.

But as usual in Ohio, Hansen’s resignation, instead of speeding up reforms, has spawned further delays in the accountability system for charter sponsors. A new panel was appointed to decide how to evaluate authorizers — even though the law mandating such evaluations was passed three years ago.

Many of these problems require a slew of arcane, even boring regulatory or statutory fixes, as suggested in a comprehensive report put together in December 2014 by the Fordham Institute. They include limiting conflicts of interest, holding sponsors and management organizations accountable for their schools’ performance, prohibiting “sponsor hopping” by ineffective schools, and closing loopholes that dilute accountability.

However, it turns out that some of the operators of the worst charter schools will not sit back quietly and accept tougher regulations.

Among the largest donors to Ohio politicians are those running for-profit charter schools. The founders of Electronic Classrooms of Tomorrow (ECOT) and White Hat Management have donated more than $6 million to Ohio politicians — almost all Republicans — since charters came into existence in Ohio. House Speaker Rosenberger, who pulled the charter reform bill, has been a major recipient, receiving approximately $35,000 in campaign donations.

They appear to be getting a substantial return on their investment. The for-profit charter lobby has been instrumental in pushing through legislation favorable to its interests, with one report finding charter lobbyists and legislative staff working closely on legislation.

The relationship between Republican legislators and the sector has long been cozy, so it was perhaps no surprise when retired Ohio house speaker William Batchelder began working for ECOT’s lobbying firm earlier this year.

Some point to the donations as the reason this year’s charter reform bill was stopped.

“I was in the legislature for four years and I saw a lot of powerful interests in Columbus — I never saw anybody get everything they wanted, except for charter schools,” Dyer, the former legislator, said.

StudentsFirst’s Harris describes the whole thing as a “borderline pay-to-play situation.”

Chambers, of the Ohio Alliance for Public Charter Schools, denied any suggestion of influence peddling. “Legislators receive campaign donations from many different industries, organizations and individuals. These donations are one way citizens practice free speech that is protected under the Constitution,” she told The Seventy Four in an e-mail. “To imply that a donation can cause a legislator to concede on any issue is misguided and distorts the democratic process.”

ECOT and White Hat schools did not respond to multiple requests for comment, though in a Sept. 11 article in the Columbus Dispatch, an ECOT spokesman and lobbyist focused attention on traditional public schools, saying, “It’s interesting that the district schools, which make no mistake, are government-run schools, are complaining about their government money when they continually fail to do their jobs.”

ECOT and White Hat have been generally successful in getting their legislative priorities enacted — not so much in educating children. ECOT received an F grade from the state in every aspect of its value-added scores (i.e. student progress over time).

White Hat’s Alternative Education Academy received an F on its value-added state report card. Another White Hat school — a dropout recovery program — had a graduation rate of 1.3 percent, or 2 students out of 155. With the 10 percent improvement loophole, the school could stay open so long as its grad rate inches up to just 1.5 percent over two years.

No matter. When performance measures produce unflattering results, some charter groups immediately respond by demanding that the rules change. For example, Ron Adler of the pro-charter Ohio Coalition for Quality, recently complained that the state’s value-added measure of student growth was “inequitable” and unfair to charters. The group argued for a different measure that it claims more accurately accounts for factors outside schools’ control, such as whether students live in poverty, are learning English as a second language, or have a disability.

But a Cleveland Plain Dealer story found that education researchers were unanimous in saying the current approach, which looks more precisely at individual student growth, was better than the charter group’s statistically crude alternative.

Many school choice supporters believe that creating a free market will inevitably weed out low-performing schools as parents gravitate to better alternatives. Conservatives and libertarians in particular have endorsed this view. As Louisiana governor and presidential candidate Bobby Jindal put it, parents are “the best accountability system we have.”

Chambers, of the Ohio Alliance for Public Charter Schools, makes a similar case: “Charters are held to a very high level of accountability in that parents can withdraw their children from charters that fail to meet their expectations.”

There might be something to this idea. A study in Texas found the state’s lightly regulated charter school sector improving significantly over time, potentially due to parent demand for better options.

But Ohio calls into serious question whether parent accountability is enough.

Dyer argues that parents choose schools for a variety of reasons that might have nothing to do with academics — even basing choices on ads or celebrity endorsements.

Electronic Classrooms of Tomorrow spent $2.27 million in public money on advertising to attract students to its F-graded schools in 2014 — and that figure does not include the ad dollars spent by its for-profit management company, which are not subject to public disclosure.

“People sometimes make bad decisions,” Dyer said. “The idea is to create a market that ensures that as few of those kinds of decisions are made as possible.”

Research from New Orleans confirms that families consider a variety of non-academic factors when choosing schools, and the lowest-income families often have the least access to the most academically rigorous schools.

Macke Raymond, a CREDO researcher who has documented some of Ohio’s mediocre results, made news when she said, “I actually am kind of a pro-market kinda girl. But it doesn’t seem to work in a choice environment for education … the policy environment really needs to focus on creating much more information and transparency about performance than we’ve had for the 20 years of the charter school movement. We need to have a greater degree of oversight of charter schools. But I also think we have to have some oversight of the overseers.”

Why can’t we trust parents to provide that oversight themselves? Kochensparger, the teacher who testified about corrupt practices at a Dayton charter school, describes an elaborate charade at her school meant to deceive parents.

“For one year, I served as the school’s public communications director in addition to teaching,” she said. “I went to the … PR training program meetings. The training emphasizes promotion of the school’s academic achievements — even if those achievements are inflated or fabricated.”

In this kind of climate, schools don’t just compete on academic quality but on marketing prowess. And contrary to Jindal’s suggestion, New Orleans has not created a laissez faire market of schools, but rather a tightly regulated ecosystem in which the government holds schools to strict accountability standards.

Doug Harris, a Tulane University economist who has extensively studied New Orleans schools, told The Seventy Four in a recent interview, “One possible lesson of New Orleans is that just making it a free-for-all is probably not going to be the right approach.”

The contrast between New Orleans’ largely successful charter sector and Ohio’s disastrous one strongly suggests that parent accountability is not enough to guarantee academic quality.

When school reformers refer to “adult interests” in education, they’re often taking thinly veiled jabs at teachers unions, which some argue have been an obstacle to meaningful reform.

But teachers are not the only political interest with something at stake in education, and teachers unions in Ohio have actually helped push for improvements in charter school regulation.

The question, now, is whose interests will prevail in Ohio?

After major newspapers across the state lambasted the lax charter regulations, highlighting the need for reform, many policymakers and advocates are now optimistic that change will come.

Dyer is hopeful something will get done, but is concerned that the implementation will inhibit progress. “I'm more wary of the reforms because so much will be dependent upon the Ohio Department of Education [ODE] having its act together… If ODE doesn't take a tough stance for quality, then I'm afraid many of the reforms could go for naught,” he wrote in an email.

But both Chad Aldis and Greg Harris believe that meaningful legislation will pass.

“I think we’re in a situation where we’re going to solve a lot of the problems,” Harris says. “The tragedy is just that it took this long.”

1. Disclosure: I worked as an intern at StudentsFirst’s national office for a summer a few years ago. (Back to story)

2. Many of Ohio’s sponsors are regionally based, so a given charter school does not have 70 separate options of sponsors; the number of potential sponsors will likely depend on the region. (Back to story)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)