How an Online Personalized Preschool Experiment Could Change the Way Rural America Does Early Education

Garfield County, Utah, is about 5,200 square miles, and has just about as many people.

Among its nine schools is Escalante School, which enrolls roughly 75 children from kindergarten through sixth grade. This year, eight of its future students are enrolled in Upstart, an online personalized learning preschool program that children complete from home.

“When we talk about the differences between rural and urban low-income families, rural low-income families just may not have as many opportunities or resources available to them, just because of the area that they live in,” Melinda Dalton, a coordinator with Upstart, told The 74. Dalton is a liaison between Waterford, the nonprofit technology and research firm that runs Upstart, and two rural school districts in Utah.

Upstart launched in Utah in 2009 as a low-cost option to expand preschool in a state that didn’t have a state-funded program. Since then, it has been a particular boon for the state’s rural areas. About 30,000 Utah children have gone through the program over the past eight years, with about 14,150 participating this school year. It has also now spread to seven other states, where 700 early learners are enrolled.

State and federal policymakers are increasingly recognizing the value of early education, especially in keeping the achievement gap more at bay for disadvantaged children before they enter kindergarten. Preschool programs teach younger children early literacy and math skills alongside essential social-emotional skills. About 1.5 million 3- and 4-year-olds were served in state-funded preschool programs in the 2015–16 school year, more than double the number enrolled in such programs in 2002, according to the National Institute for Early Education Research.

The Upstart program prioritizes low-income children, English language learners, and children who live in rural areas. After several years of waiting lists, which climbed to more than 1,700 families two years ago, Utah legislators authorized more funding. The program received $11.5 million this year. Last year the list was smaller and only had children from higher-income families, said Claudia Miner, vice president of development at Waterford.

Families agree to use the program 15 minutes a day, five days a week for literacy. There are also science and math options for students who want to spend more time with the program. Program administrators will provide laptops and internet services to participating families that don’t have them.

Other members of the family are free to use the software as well, Miner said.

“We allow the family to put additional children on the program. Everybody has his or her own individualized learning path. We encourage that,” Miner said, adding that some parents learning English set up their own accounts to get additional language exposure.

The main benefit of the program is that it’s totally personalized, Dalton explained.

“If they need to be introduced to the letter C six times before they can understand that … that’s great, they have that opportunity,” she said. “If they catch it on the first time … they can move on to the next level.”

Upstart has gotten the federal nod of approval: Waterford received an $11.5 million federal Education Department grant in 2013 to expand to more rural areas in Utah.

A 2016 study by the Utah Office of Education found that tests of participating students “showed that Upstart participation had a large impact on students’ early literacy skill development.”

Kimberly Veator’s son Tyson, now a kindergartner, did Upstart last year, alongside an in-person pre-K program.

Technology isn’t going anywhere, and it’s important that young children use it for more than games, she said. Tyson learned a ton, and his kindergarten teacher noticed his advanced skills in his beginning-of-the-year testing, Veator said.

“It seemed like he flew through it,” she said.

Though she’s heard that finding the time was a challenge for other families, the 15 minutes daily wasn’t a problem for her family, she said, because they got into a routine using it and Tyson knew he had to finish Upstart before he got any other screen time.

Brandon Jensen’s daughter Marissa used the program in previous years and was able to start kindergarten reading, and his younger daughter Loryn uses it now. Loryn in particular likes to keep using the program even after her required 15 minutes are up.

“This is the best program out there,” he said.

The girls like the songs in the program — often traditional songs, like the ABC’s, remixed with a new lesson — and will go around the house singing them even when they aren’t using Upstart.

The program in recent years has grown outside of Utah. More than 700 children participate in pilot programs in Idaho, Indiana, Ohio, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania.

Results from pilots in Mississippi, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Indiana show that children tested as high as an “advanced first grade” level on some specific reading skills, according to tests conducted by Waterford. The Pennsylvania pilot, which started earlier this year in Philadelphia, enrolled 23 refugee families. Among those students, whose first language isn’t English, half scored at “kindergarten intermediate” levels or higher on reading tests.

Philadelphia is, of course, far from the rural setting that has seen much of Upstart’s growth. Mayor Jim Kinney in 2016 started a universal preschool initiative to create 6,500 seats over five years, but there aren’t enough seats yet, and they sometimes aren’t convenient for families, said Jenny Bogoni, executive director of the Read by 4th Campaign, a group of Philadelphia nonprofits, churches, and other organizations committed to get children reading on grade level.

Waterford came with $400,000 to fund the program, computers, and internet access for a year, and although it didn’t provide the social-emotional or executive function skills, “it was 100 opportunities for pre-K-age children to have access to resources that weren’t here in Philadelphia,” she said of the 100 children who enrolled.

Though Upstart teaches letters and numbers, an online program can’t teach those executive function and social-emotional learning skills — things like focusing, paying attention, or taking turns — often credited as some of the lasting benefits of preschool.

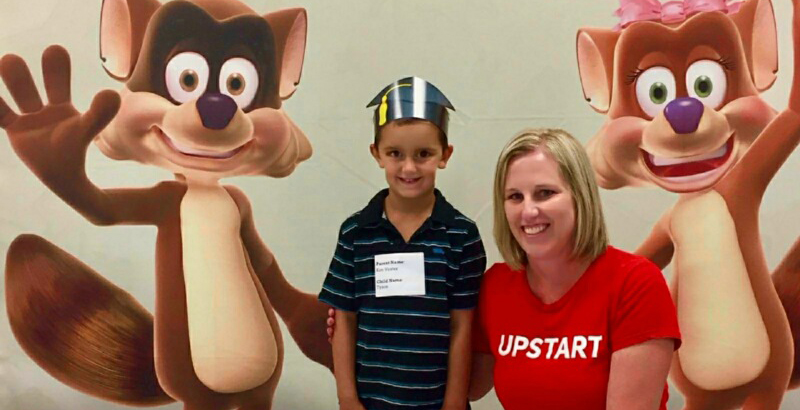

As a way to bring the early learners together, liaisons for Utah’s 18 most rural districts host kindergarten readiness events, like a Halloween party or story time at a library, Miner said, and every program holds a graduation ceremony. Parents get a certificate to go with their child’s “diploma.”

Some children who use Upstart are enrolled in other pre-K or day care programs, and Upstart coaches will email with parents to share, for example, the importance of play.

“We work through the parents,” Miner said. We try, in training, to reassure the parents that they know more than they think they know,” Miner said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)