Exclusive Data: Educators’ ‘Careless’ Child Abuse Reports Devastate Thousands of NYC Families

Only 1 in 3 investigations prompted by teacher calls found any evidence of maltreatment. But even when a case is dismissed, “it doesn’t stop the PTSD”

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Correction appended Oct. 6

When child protective services investigated Shalonda Curtis-Hackett’s family for neglect in 2021, the Brooklyn mom could measure the personal toll in pounds lost: 20.

She tried to fight the clawing thoughts that her caseworker “could try and snatch my kids,” a vision she says she still can’t escape in her nightmares.

Though the agency eventually found no evidence her children were malnourished — her husband is a professional chef — the process of having a welfare worker inspect their Bushwick apartment, check the fridge for food and ask prying questions deeply disturbed her children, who are now 8, 10 and 15.

“My children are happy-go-lucky kids and I’ve had to adultify them and tell them about the world much faster than I wanted to,” Curtis-Hackett said.

The mother, who was also PTA president at her younger children’s school at the time, believes the report came from a K-12 staffer who said her kids’ bones were sticking out, an observation made while the children were attending class via Zoom at the time.

If so, the family is among the thousands of New York City households — disproportionately Black, Hispanic and low income — subjected to unfounded investigations into abuse or neglect initiated by calls from their children’s school.

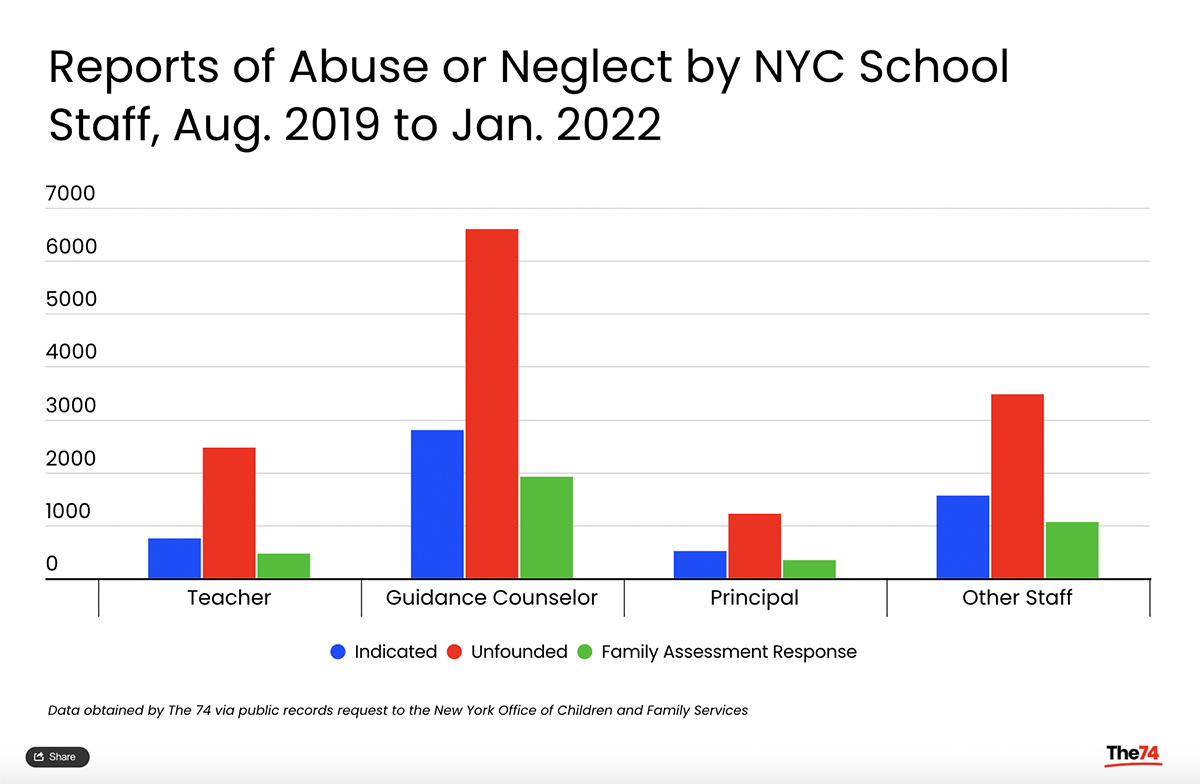

In fact, between August 2019 and January 2022, city school employees made over 13,750 false alarm reports to the state child abuse hotline, according to data obtained by The 74 through a public records request to the Office of Children and Family Services.

Over that time span, the vast majority of school-based reports were ultimately unfounded, including at least 58% of calls from guidance counselors, 59% of calls from principals and 67% of calls from teachers. Less than 1 in 3 teacher reports led to any evidence of wrongdoing.

“Teachers, out of fear that they’re going to get in trouble, will report even if they’re just like, ‘Well, it could be abuse.’ It could be. It also could be 10 million other things,” said Jessica Beck, a middle school English teacher in the Bronx.

Those reports spur investigations that, at their most dire, can lead children to be separated from their parents — a trauma associated with elevated risks of mental health challenges, incarceration and even early death. Even when closed and dropped, investigations can stay on parents’ records for years afterward and erase job prospects in youth-serving fields.

Kamaria Excell is a social worker who has helped dozens of parents recover from the damaging process. She led a 12-week healing program with the community-based organization JMacForFamilies. The vast majority of participating parents — 95%, she estimates — had investigations that were ultimately dismissed. But the shame, anger and eroded trust did not fade.

“Families deal with the repercussions of careless [child welfare] investigations for years after,” she said.

When a case gets closed, Curtis-Hackett, the Brooklyn mom, added, “it doesn’t stop the PTSD.”

‘When in doubt, report’

In total, only 24% of investigations prompted by calls from school staff found evidence of abuse or neglect compared to a citywide rate of 36% in 2020 — meaning K-12 workers, teachers especially, make allegations that do not get substantiated far more often than most other professions. (Another 16% of K-12 calls led to an alternate response for children determined not to be in imminent harm and 59% were dropped outright.) Even that rate likely overstates the true level of maltreatment, family law attorney David Shalleck-Klein said, because it’s a metric the agency determines “unilaterally” and includes cases that may ultimately be dismissed in court.

The issue extends beyond Gotham, with similar rates of unsubstantiated reports from school staff nationwide. Among mandated reporters, K-12 workers are the most likely to report abuse or neglect and the least likely to have their allegations find evidence of wrongdoing, data show.

Like most states, New York requires educators, child care providers, law enforcement officers, health care professionals and social workers to call a hotline if they believe a young person may be experiencing abuse or neglect. But, in practice, that decision is always a judgment call, said Beck, the Bronx middle school teacher. And in NYC schools, it’s a call made by teachers who are mostly white about students who are mostly Black and Hispanic.

“What looks like neglect to a teacher who has privilege might actually be poverty,” said Beck, who is white.

For example, educators are trained that poor hygiene can be a sign of neglect. But if a kid in her class smells, the teacher will speak with the parents rather than immediately calling in a report, she said. Some colleagues in the same situation, though, may call the state hotline, plunging that family’s life into the havoc of a neglect investigation.

The ethos is “when in doubt, report,” said Darcey Merritt, an associate professor of social work at New York University.

“Instead of immediately reporting a suspected neglect situation, find out how to address that need that’s being unmet first,” she suggests.

That is not what a social worker at a Bronx transfer high school — small schools designed to re-engage students who have dropped out or fallen behind — sees on the ground, unfortunately. She asked not to be identified for fear of getting into trouble at work.

“It’s totally C-Y-A, cover your ass. If you’re unsure, just call,” she said.

“They never provide information on what happens after the call,” she continued. “Mandated reporters don’t know that, many times after making a call, 24 hours [later] someone’s going to show up to this person’s house … and start conducting an investigation: a search of their home, checking counters, checking their cabinets, strip searching their young children to check for any bruises or marks, depending on the allegation.”

Instead, the training sessions she has attended have begun by projecting the names and pictures of young people who have died by parental abuse, the social worker said, a tactic she considers “fear mongering.”

The Department of Education said it cares deeply about the well-being of students and is committed to providing support and care at the earliest opportunity.

“While every NYC Public School member is a mandated reporter, we are focused on connecting with children and families who may be in need, providing them access to the vital interventions, supports and services they need to stay safe,” DOE spokesperson Suzan Sumer said in an emailed statement.

The Administration for Children’s Services, the city agency that investigates suspected abuse and neglect, said it is working to cut down on unneeded reports. Overall, school and child care-based reports fell 17% from spring 2019 to spring 2022, it said.

As per a 2021 state law, mandated reporters are required to undergo implicit bias training. And this fall, ACS will hold a series of five-hour trainings in collaboration with the NYC Department of Education to help school staff better understand the citywide resources they can refer families to rather than calling the child abuse hotline, the agency said. Only one representative from each school, however, is required to attend.

“We take our mandate of protecting children and supporting families seriously, while simultaneously being committed to reducing unnecessary child protection involvement with families, particularly families of color,” a spokesperson wrote in an email.

Of the 41,500 NYC investigations in 2020, 36% found evidence of abuse or neglect and 86 children died, according to the Administration for Children’s Services. The large majority of those deaths “were unrelated to abuse or neglect,” the agency wrote. However, when a child is killed as a result of being beaten or neglected by a family member, the agency frequently comes under fire for failing to investigate or properly follow through on earlier reports of abuse.

‘School-to-ACS pipeline’

In New York City and across the nation, involvement with child protective services breaks decisively along racial lines.

Citywide, some 90% of children named in ACS investigations are Black or Hispanic, while, together, those racial groups make up 60% of NYC young people. Even among neighborhoods with similar poverty rates, those with greater shares of Black and Hispanic residents face higher rates of investigations, research shows.

Child protective services involvement becomes so normalized in many low-income communities, Merritt has noticed, it changes people’s vernacular.

“These ACS-impacted moms literally say, ‘Well, I caught an ACS case,’” as if they’re referring to the criminal justice system, the social work professor said.

Meanwhile, more privileged communities are often unaware of the disastrous effects that system can have, said her NYU colleague Anna Arons, assistant professor of law.

“It is really easy to be a person with money in this country, … particularly white, and not have any sense of child welfare services as anything more than people who are genuinely helping children,” she said. “You might never know there are 50,000 investigations every year in New York City, which is really an astronomical number.”

Curtis-Hackett, for her part, has taken the situation into her own hands. After being reported to child protective services, she no longer wants her family to participate in a system she calls the “school-to-ACS pipeline.”

Last year, she pulled her kids from the public school system. Now, they homeschool.

“I don’t trust the [Department of Education],” she said. “I will not allow my children to be collateral damage.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated national figures for the number of children in 2020 who had died, suffered abuse or neglect, and been reported to CPS by any source, not just educators. Those contextual data have been corrected to reflect New York City’s rates.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)