The Science of Reading and Play Go Hand-in-Hand. Schools Must Make It Happen

Roberts & McCormick: Activities like blocks, drawing and dramatic play can make learning feel like a game for young kids. But the gains are real.

Walk into many kindergarten classrooms, and you’ll find kids sounding out letters in a phonics lesson or learning vocabulary words through an interactive read-aloud. These scenes are part of the growing movement to teach literacy using evidence-based practices known as the science of reading. And it’s working: states like Mississippi, Tennessee and Louisiana have seen real progress in students’ literacy scores. But as schools work to help young students gain grade-level skills, there’s a real risk of squeezing out something just as vital to early learning: play.

At first glance, play and explicit reading instruction can seem at odds. Under pressure to improve reading outcomes after years of falling or stagnant scores, schools might cut recess or limit imaginative activities to make time for instruction. But this is a false choice. Research shows that play is not only compatible with the science of reading — it’s a powerful way to build the very skills kids need to become strong readers in the first place. In fact, children learn best through hands-on, engaging activities that make new sounds and words stick.

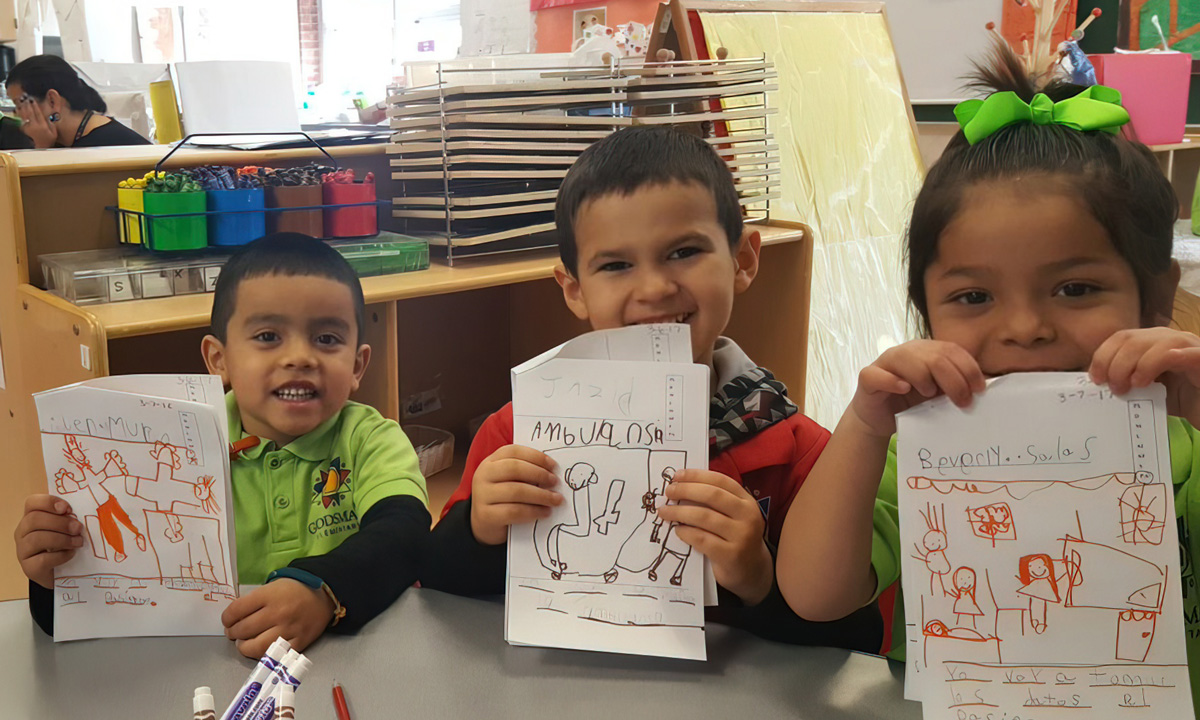

That’s because play isn’t just fun; it’s serious learning. Guided play — where teachers set up fun activities with clear learning goals — is more effective than direct instruction in promoting learning, particularly for young kids. For instance, studies have found that using activities like blocks, drawing and dramatic play to deliver literacy instruction improved children’s oral language, letter recognition and ability to sound out letter blends and words. Learning to read felt like a game for kids, but the gains were real.

The Boston Public Schools’ evidence-based Focus on Early Learning program shows how this can work at scale. There, children in pre-K through second grade spend most of the morning acting out stories, playing with letters and exploring books — all activities carefully set up by teachers to align with science of reading principles. Unlike many districts that have shifted instruction in the early grades to be more traditionally academic, Boston has made a play-based approach a focal point of K-2 learning. The results show it’s working: Students in the program consistently display substantially stronger literacy and language skills than their peers who are not enrolled.

In districts nationwide, programs like Tools of the Mind and Every Child Ready go further. A Tools pre-K classroom, for example, uses themed dramatic play to teach early reading skills; in a pretend grocery store, children might create shopping lists (writing), sort items by categories (vocabulary) and engage in conversation with peers about what to cook for dinner (language development). Every Child Ready classrooms use songs, stories and games to teach sounds and letters, with teachers closely tracking progress to tailor instruction. These approaches combine the best of structured literacy and joyful learning to help children develop the skills to be ready for kindergarten. Studies show that kids in Every Child Ready outperform peers on foundational literacy skills, while kindergartners in Tools of the Mind experience significant boosts in self-regulation and social skills.

This combination of play and evidence-based reading instruction may be especially important for boys and children in schools serving primarily low-income students. As instruction has shifted toward more sit-still-and-listen activities, many boys — especially those who are among the youngest in their grade — find it harder to learn. Play-based approaches, which offer more movement and choice, can help engage boys in learning early, laying a stronger foundation for reading and future academic success.

For low-income children who are already less likely to have access to high-quality opportunities for play than their wealthier peers, that minimal play time often gets sacrificed first as schools scramble to improve test scores. By making a shift away from play, schools could unintentionally be depriving kids of one of the most valuable and evidence-based tools in their toolkits.

With two-thirds of U.S. fourth graders below proficient in reading, addressing America’s literacy gap is critical. But the answer isn’t to turn early learning into a series of drills and worksheets. To inspire a joy for learning, play is key. Reading success should not — and doesn’t have to — come at the cost of the creativity, joy and social growth that are key to the early years.

Education leaders and policymakers should promote evidence-based curricula, training and assessments that integrate both reading and play. Help teachers make literacy instruction playful and engaging, and give kids the freedom to imagine and explore as they learn, and you’ll see results.

Disclosure: The Overdeck Family Foundation provides financial support to Tools of the Mind, Every Child Ready and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)