Early Childhood Innovation Center Shores Up Delaware’s Early Learning Workforce

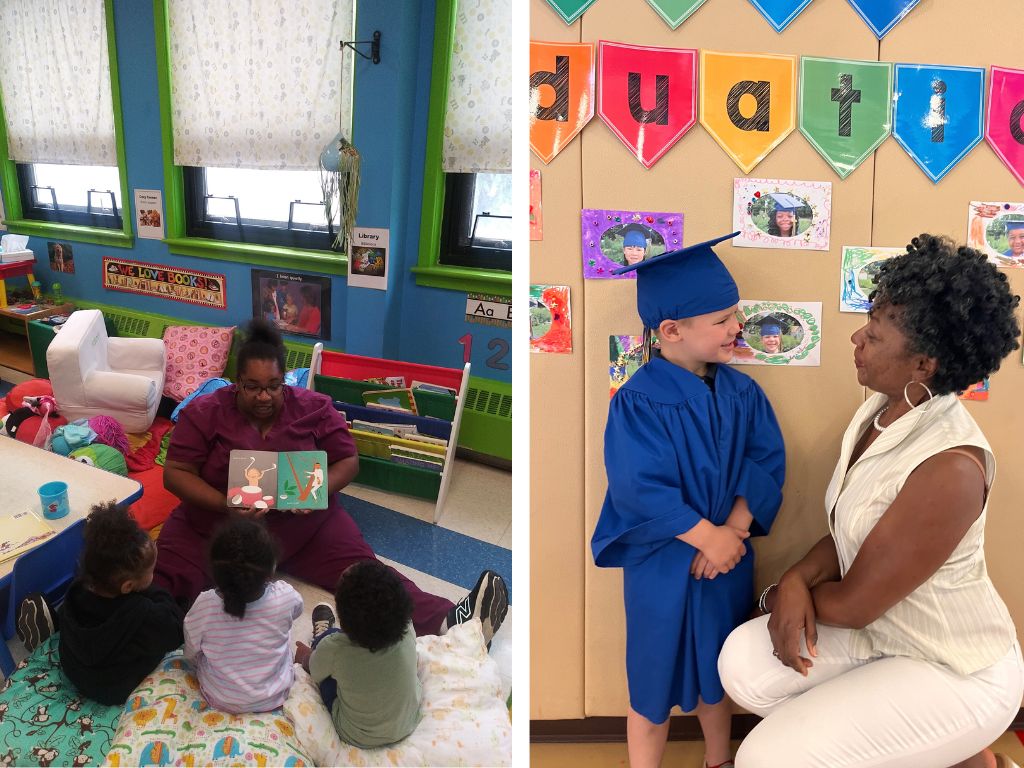

A statewide initiative in Delaware helps early childhood educators overcome barriers to pursuing advantage credentials.

When a 2-year-old showed up at the Salvation Army Early Childhood Learning Center in Wilmington, Delaware, most of the staff assumed she couldn’t speak, but one of the teachers, Jazzie Tribbett, saw something the others didn’t.

“She could talk,” Tribbett explains, “but she had difficulty pronouncing words because of the thickness of her tongue. She came in with a lot of struggles.” Tribbett helped the family seek out speech support, and it turns out she was eligible for services. After receiving speech therapy, the child, now 3 years old, is able to make herself understood.

Tribbett, who received her child development associate (CDA) credential in the spring through Delaware State University, said she was able to recognize signs that the toddler needed a speech evaluation because of her work with a seasoned early educator mentor with the program.

How Delaware’s Early Childhood Innovation Center Supports Early Educators

In 2021, the state of Delaware opened the Early Childhood Innovation Center (ECIC), a workforce center dedicated to helping early learning professionals attain CDAs or an associate degree or a bachelor’s degree in the field. The ECIC provides career counseling, mentorship and financial support to break down barriers that often inhibit early educators from pursuing advanced credentials. This spring, the ECIC opened a new facility, which is now the state’s hub for career advancement in early learning.

Kimberly Krzanowski leads the center. She previously held roles as a preschool teacher, a child care center director and executive director of the Office of Early Learning at the Delaware Department of Education. In 2021 when then-governor John Carney said there was money in the budget to do something “big and bold” for young children, she recalled responding, “Well, I happen to have a folder over here full of hopes and dreams.”

Krzanowski said it took four years, a ton of planning, and significant investment including $20 million of state funding and $10 million in federal dollars from the American Rescue Plan Act to open the center.

Though the ECIC building is located at Delaware State University, all of the state’s higher education institutions are participating in the project, as well as University of the Potomac, which offers an online early childhood degree for Spanish speakers.

This is an opportune moment for early learning in Delaware. The new governor, Matt Meyer, the father of a young child and a former public school math teacher, recently met with child care leaders and emphasized the importance of workforce pathways in the field; he also attended the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the new site.

To date, almost 700 students, including Tribbett, have taken advantage of various elements of the programs offered by the center, including mentorship to guide them through the requirements for the credential they’re pursuing and financial support to cover related costs.

Mentorship, one of the center’s signature efforts, has been underway since the program launched four years ago. A high school student, college student or early educator already in the workforce (which ECIC refers to as a “scholar”) can participate to be paired with an experienced educator-coach (known as a “navigator”) who will work with them toward the credential they’re pursuing. The ECIC provides each scholar with a laptop and a $500 stipend and pays their assessment fees.

The program also offers financial incentives for career advancement. When a scholar completes six months working in a licensed child care program, they receive a $1,000 bonus. The size of the bonus goes up with each step on the degree ladder — $5,000 for an associate degree, $10,000 for a bachelor’s degree.

A Mentorship Model Boosts Educators’ Confidence

Tribbett’s mentor, Phyllis Roland — an educator living in Bear, Delaware — sees the potential for ECIC to increase the number of educators in the state and to boost the quality of education provided.

Roland has decades of classroom experience and has been an early childhood advocate for years. She has lobbied for child care in Delaware and in Washington, D.C. “The child care trenches are demanding and time-consuming,” she wrote in a 2022 commentary. “And those conditions often make it hard to advocate for yourself and for your colleagues.”

Roland visits Tribbett’s class twice a month, on top of two reflective monthly Zoom meetings. As part of her CDA, Tribbett composed a two-page philosophy statement containing the assertion: “I believe that by observing the children that enter my care I can meet them where they are and develop a plan to be able to help them reach their goals.”

Roland praises Tribbett for providing a positive example for the children she teaches, who often have issues at home. “You’re preparing them to be successful in a classroom, so your role is very important,” she tells her mentee.

Tribbett said the pairing has boosted her confidence, a factor that might keep her in the field and drive her to tackle higher levels of certification. Tribbett, who is the mother of six children, is currently deciding between applying for her paraprofessional certification at Delaware Technical Community College or working toward an associate degree.

“As a coach,” Roland said, “all I had to do was help Jazzie articulate everything that she does on a daily basis. I think she never had an opportunity to toot her own horn, and so that’s what she did. She’s very skilled and very capable.”

Krzanowski sees this kind of alchemy as vital to the field — and to Delaware’s economic well-being. “We’re seeing our matriculation numbers really increase,” she said, “because now they’re like, ‘If I did this CDA, now I’m ready to go to the community college or to somewhere else.’ And they have that confidence. It’s life changing.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)