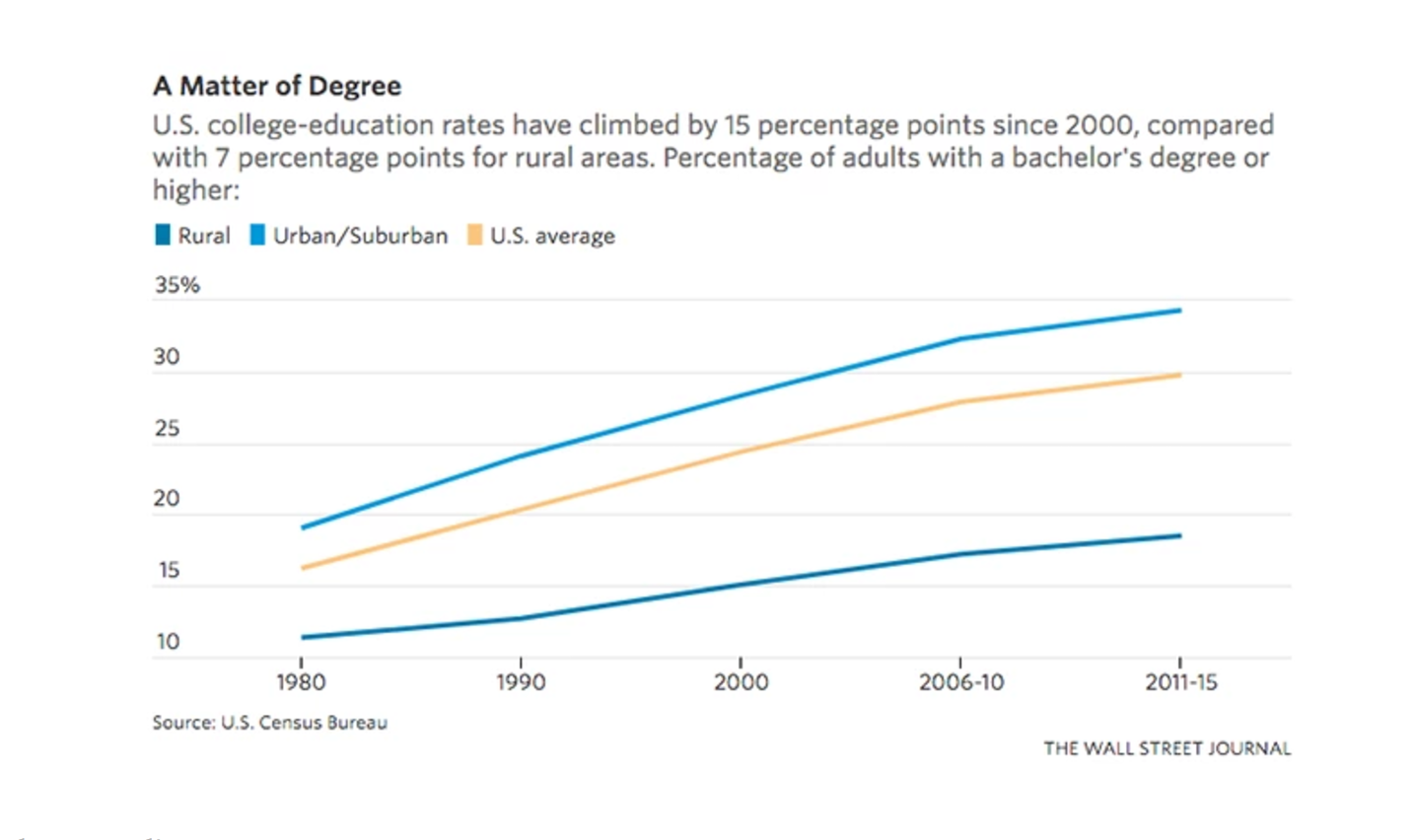

When College Grads Don’t Come Back Home: New Numbers Show a Widening Urban-Rural Education Divide

The rate of college attainment in rural America is just a little over half that of urban and suburban areas, reports The Wall Street Journal, citing Census data in a story Tuesday on the heartland’s ongoing brain drain. While reports abound of educated millennials deserting Southern and Midwestern homes for coastal metropolises, college graduates often transplant themselves to regional capitals just a short distance away, remaining in red states but leaving their small towns behind.

Interviewing parents and employers in tiny Mahaska County, Iowa, the paper found many complaining of limited economic opportunities and cultural attractions to attract young professionals, especially compared with the allure of Iowa City and Des Moines. Once they collect their degrees, most stick in their college towns or move on to still-larger urban centers.

“Many young people in rural communities now see college not so much as a door to opportunity as a ticket out of Nowheresville,” the authors write.

Although ambitious youngsters have always been drawn to the bright lights of New York and Los Angeles, the exodus from small towns has accelerated in recent decades as industrial jobs have disappeared and the Great Recession took its toll. In 2000, Mahaska County sent 73 people to nearby Johnson County (home of the University of Iowa) and received 71 people in return. In 2014, it sent 170 people and received around 20 back. Overall, the population of Mahaska is roughly the same as it was at the turn of the century, while Johnson is nearly one-third larger.

Figures at the county level are easy to miss, but across a few decades and thousands of miles of highway, they become inescapable. According to the Pew Charitable Trusts, 759 rural counties lost inhabitants between 1994 and 2010; that period marked an economic boom compared with the years that followed, when an astonishing 1,300 such counties in 46 states saw their populations dwindle. Seventy percent of manufacturing-dominated counties shrunk in size following the recession and credit crunch of 2008, according to the Brookings Institution.

But cities aren’t simply acting as magnets, drawing the creative and talented kids away from languishing communities. Those students are also being repelled from their hometowns — not only stunted by a dearth of job openings, but also prodded by their families and schools. Sociologists Patrick Carr and Maria Kefalas, who have studied the movements of young people in economically depressed regions, note that a gulf often opens in high school between those groomed for prosperity in other places and those resigned to staying where they were raised.

“As achievers are pushed, prodded, and cultivated to leave, and credit their teachers for being integral to their success,” they write, “the stayers view school as an alienating experience and zoom into the labor force because few people are invested in keeping them on the postsecondary track, and the lure of a regular paycheck is hard to resist.”

That two-track system slowly contributes to a national divide that manifests itself geographically, educationally, and socially. In a long data feature earlier this month, Vox highlighted the work of researchers who had dropped in on high school reunions in hollowed-out hamlets. They found a stigma affixed to those who stuck around after graduation, accompanied by important differences in personal outcomes and worldview. People who left their birthplace were less likely to fear “foreign influence” over American society, less likely to attend a funeral of someone under the age of 65, and less likely to express support for President Trump.

Meanwhile, the gap in educational attainment is not merely one of college graduates versus everyone else. According to the 2008-2012 American Community Survey, 467 counties across the United States demonstrate low levels of high school completion (i.e., 20 percent or more of the working-age population lacks a high school diploma) as well. In the 21st century, a diploma is no guarantee of even subsistence wages, and dropping out is tantamount to committing economic suicide. Of those low-attainment counties, 80 percent are rural.

As parents watch their sons and daughters leave home and business owners scour for qualified job applicants, the small towns around them are sapped of vitality. The question posed by one Mahaska County employer is one that is increasingly difficult to answer:

“How are we going to replace that workforce? There are a lot of people leaving the community, and they’re not coming back.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)