U.S. Students’ Scores Stagnant on International Exam, With Widening Achievement Gaps in Math and Reading

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

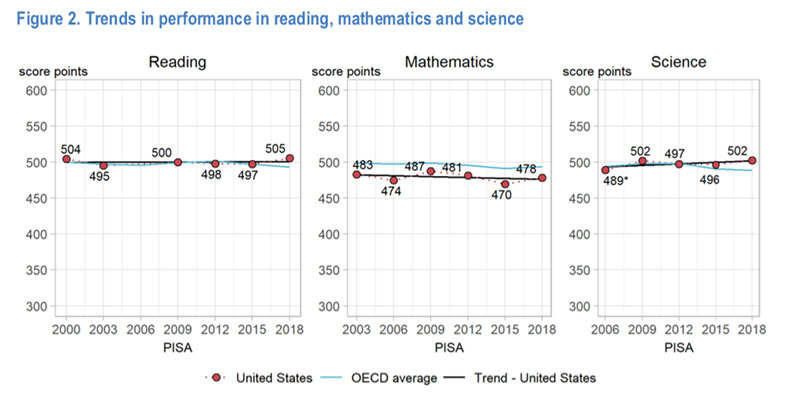

American teenagers’ overall reading, mathematics and science literacy scores were stagnant on an international test last year, showing no improvement from three years ago. Meanwhile, the achievement gap between low- and high-performing students widened in mathematics and reading but narrowed in science.

Last year, U.S. 15-year-olds scored above average in reading and science and below average in math among countries that participated in the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), according to results released Tuesday. The assessment, developed and coordinated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), is administered every three years and provides a global view of American students’ academic performance compared with teens in nearly 80 participating countries or education systems.

Compared with scores in other regions, U.S. teens ranked ninth in reading, 31st in math and 12th in science. Nations with comparable student scores included Australia, Germany and the United Kingdom.

Between 2015 and 2018, the U.S. improved its global ranking in each of the tested subjects — but not for the right reasons, Peggy Carr, associate commissioner of the assessment division at the National Center for Education Statistics, said on a call with reporters.

“At first glance, that might sound like a cause for celebration, but it’s not,” Carr said. While U.S. scores remained steady, student performance in multiple participating countries declined. “It’s not exactly the way you want to improve your ranking, but nonetheless that ranking has improved.”

Although average scores in reading and math showed no long-term change, the average score in science was higher in 2018 than it was in 2006. However, the U.S. science score has been flat since 2009.

U.S. PISA results were less grim than the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores released in October. On that test, math scores were stagnant while reading scores went down. Similar to NAEP, PISA highlighted a widening gap between high- and low-performing students in math and reading. As is the case in most countries that participated in PISA, socioeconomically disadvantaged students performed poorer than their more affluent peers.

On reading, for example, 27 percent of advantaged students and just 4 percent of disadvantaged students were top performers on the test. Across OECD countries, 17 percent of advantaged students and 3 percent of disadvantaged students were top performers in reading. In math and science, socioeconomics were a strong predictor of performance across participating countries. In the U.S., socioeconomics accounted for 16 percent of the variation in PISA math scores and 12 percent of performance differences in science.

In some countries, such as Lebanon and Bulgaria, PISA results show wide performance gulfs between schools, said Andreas Schleicher, OECD’s director for education and skills. But that’s not the case in the U.S., where the bulk of the variation occurred within schools rather than between them. In the U.S., he said, “it’s not so easy to pinpoint a few schools and say, ‘That’s where all of the problems come from.”

But the growing gap between high- and low-performing students is alarming because “students who do not make the grade face pretty grim prospects,” he said.

Math scores in the U.S. on PISA are most worrying because they’re below the OECD average, said Anthony Mackay, CEO and president of the National Center on Education and the Economy. But across subjects, he said, the PISA results should serve as a wake-up call for policymakers, whom he urged to look at higher-performing nations as models for improvement. Across subjects, students from China and Singapore outperformed teens in other countries. The Philippines and the Dominican Republic consistently scored at the bottom.

“Generally, we need obviously to be investing more in the early years, and that’s a message that’s come from so many of these higher-performing countries,” he said. “Secondly, they are very clear about investing in the quality of teaching all the way from how they recruit and how they retain teachers [to] how they continue to ensure that there is deep professional learning going on.”

An emphasis on educational equity is also key, he said. The highest-performing countries, he said, are “constantly supporting those who need the support to catch up.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)