There’s an App for That: How Louisiana Students Bounced Back from a Nation-leading Drop in Math Performance — and Kept Going

Since COVID-19 forced school closures last spring, a team of economists at Harvard University has been tracking the progress of students nationwide who use an online learning platform created by the nonprofit Zearn Math. Because Zearn is an app, it supplies unusually detailed and immediate data, allowing researchers to watch in real time.

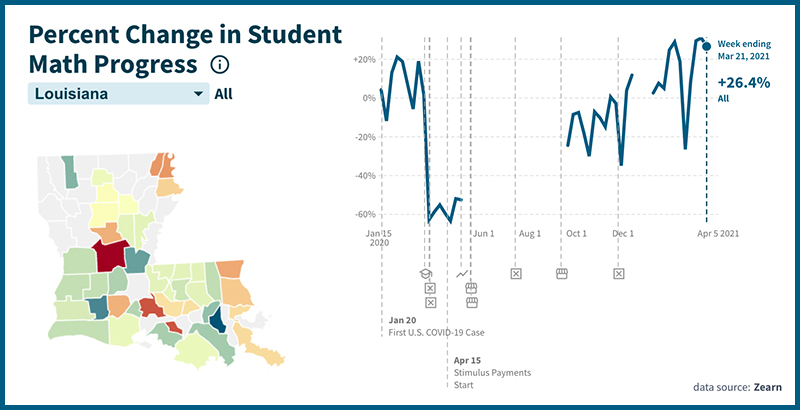

After schools had been closed for six weeks last spring, it revealed that the steepest academic drop took place in Louisiana, where student progress overall fell more than 50 percent across the board, and more than 70 percent for low-income students.

But when Zearn co-founder and CEO Shalinee Sharma looked to see how students were faring at the pandemic’s one-year mark, she was stunned to see that Louisiana’s had posted some of the country’s largest increases in progress — the biggest overall, if the spring’s post-shutdown slump is factored in.

Compared to 10 percent nationally, Louisiana students’ performance was up 31 percent. And more impressive to Sharma, progress rose significantly in most parishes (the state’s equivalent of counties) and all income brackets. Bucking the national trend of widening inequities in pandemic schooling, students in low-income schools were ahead 11 percent, while their high-income classmates were ahead by 13 percent and middle-income students by 41 percent.

Sharma dashed off an email to state education officials, pointing out the across-the-board gains. “Louisiana… is a real bright spot,” she wrote. “No other state demonstrated higher gains in student progress for as many students as Louisiana did between May 2020 and March 2021.”

Zearn is the lone academic indicator included on a pandemic data tracker created by Harvard’s Opportunity Insights, a project headed by economists Raj Chetty and Jonathan Friedman. By layering in census data, the tracker can sort participation and progress by income. The tracker provides evidence that the pandemic hasn’t just highlighted inequities among students of different demographics, but has actually widened them.

At the same time, Sharma told The 74, the data has revealed “positive deviants.” “In other states, you’d see a more uneven map,” she says. The consistency of student progress means Louisiana is seeing what she calls “an equitable recovery,” which is tied to policy decisions.

Cade Brumley, who took over as state superintendent of education in June, credits three factors for the progress. First, with one-fourth of households still lacking internet access, his department helped purchase mobile devices that allow students to connect regardless. Second, more than 70 percent of Louisiana students attend school in person, with only 20 percent attending virtually. And finally, his agency was quick to issue very prescriptive guidance to schools on everything from the conditions for safe reopening to doubling down on strategies that had been working, pre-pandemic, to spur student achievement.

Before his appointment as superintendent, Brumley had overseen the state’s largest school system, in Jefferson Parish. When he took the state post, he hired one of his top administrators, Jenna Chiasson, to be assistant superintendent of teaching and learning. At the state level, the two confronted many of the same issues they had troubleshot in the early weeks of distance learning, including getting good technology that doesn’t require an internet connection into students’ hands.

“For the first time ever, we have more devices than kids,” says Brumley.

Still, he says, it’s a stopgap solution, so the state Department of Education also is participating in a state initiative to plug the connectivity gap, bringing internet to the 25 percent of residents who have none.

Over the summer, Brumley hosted a “reopening roundtable” every Friday with education leaders around the state. Half the discussion could be about navigating the pandemic, he says, but half had to be about academics. “We have encouraged school systems to prioritize student learning, even through the pandemic,” says Brumley.

Zearn was already in widespread use throughout Louisiana when the pandemic came, as one of the top-rated programs on a state list of high-quality curricula. Officials offer financial incentives to districts and schools that adopt instructional materials ranked “Tier One,” a hard-to-attain status that means they are backed by evidence of effectiveness and aligned to Louisiana’s instructional standards. Researchers at the RAND Corp. and elsewhere say the strategy shows promise.

As outlined by the Opportunity Insights tracker, student progress nationally on Zearn fell by 29 percent during the week following school shutdowns but had bounced back and was up by more than 8 percent by late April. (Progress is student growth measured against performance in January 2020.)

When she saw the economists’ early work showing participation and progress among high-income students remaining consistent or shooting ahead, while low-income kids disappeared, Sharma “flipped out,” she told The 74’s Laura Fay. In the four years preceding the pandemic, children of different demographics had been equally successful with the program.

During the week that marked the shutdowns’ one-year anniversary, student progress nationwide was up 14 percent overall, with high-income students posting 28 percent, those at middle-income schools showing 20 percent progress and low-income students down 2 percent overall.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation provide financial support to Zearn and The 74. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative provides financial support to Opportunity Insights and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)