Research Shows That New Orleans Schools Have Improved Since Katrina. So Why Don’t Black Residents Agree?

Correction appended July 23

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

Ample evidence shows that New Orleans public schools are performing much better now than in 2005, when the destruction wrought by Hurricane Katrina led to a large-scale takeover of most public schools and the introduction of ambitious education reforms. Experts have found that students there are now more likely to finish high school, and learning gaps between black and white children have noticeably closed over the past decade.

But not everyone puts faith in those successes. According to a new paper looking at public opinion data during the period when the reforms were being implemented, New Orleans’s black majority has been more likely to perceive post-Katrina schools negatively compared with the status quo before the storm.

The paper’s authors believe those negative views are attributable to the nature of the takeover, which converted most city schools into charters and dramatically shrank the power of the local school board. Control over school governance, and access to jobs in education, passed in large part from black to white control, they write.

Co-author Domingo Morel, a political scientist at Rutgers University, has previously studied state takeovers of troubled urban school districts. His 2018 book on the subject found that heavy-handed takeovers arrogate political power from local communities and lead to less representation for minority groups in government.

In an interview with The 74, Morel said that while many believed that the educational picture had brightened in New Orleans since Katrina, black residents — the largest ethnic group in the city — were much more ambivalent.

“When you look at the general results of public opinion surveys, there seems to be a lot of support for these efforts,” he said. “But if you start looking at it a bit closer, it’s puzzling. The majority of the community is feeling very differently than this narrative that has been framed around the New Orleans reforms. The people who are mostly being affected by these policies have a certain view that isn’t really being captured in the general conversation.”

That view may soon speak with greater force, as authority over schools reverted back to the elected school board a year ago. While defenders of the post-Katrina policies can point to meaningful progress in student achievement, they will have to persuade families who feel alienated by the way that progress was realized. Further improvements could founder without their approval.

‘Young, white and shiny’

State-initiated takeovers of underperforming school districts have been an arrow in the education reform quiver for years. A string of such maneuvers took place a generation ago, when state governments (led by prominent Republicans) seized control over public education in large cities with significant black populations: Newark in 1995, Detroit in 1999 and Philadelphia in 2001.

The situation in New Orleans resembled its predecessors in some respects: Dozens of schools serving tens of thousands of students produced poor academic results in the years before Hurricane Katrina. Widespread corruption on the Orleans Parish School Board led to FBI investigations that yielded several prosecutions, including one of a former board president who pleaded guilty to accepting bribes.

But the catastrophic storm led to changes that were, in some ways, sui generis: In less than a decade, virtually every K-12 school in New Orleans converted to a charter school. White charter founders and teachers — many flown in by Teach for America — replaced veteran black educators who had long formed the backbone of the city’s middle class. And in 2010, voters even elected Mitch Landrieu, the city’s first white mayor since 1978.

The metamorphosis is now widely credited with a measurable improvement in student performance. Findings from the Education Research Alliance show increases in rates of high school graduation, immediate college entry, college persistence and college completion since the aftermath of Katrina. Additional data on later-life outcomes will become available as more students make their way through the city’s public schools, but the early returns have been hailed by experts as evidence of a citywide turnaround.

Public perceptions of the new school system have generally been seen as warm: According to regular polling conducted by the Cowen Institute — a research group formed in 2007 to monitor progress in local schools during the city’s recovery — most New Orleanians rate their schools as average or better, and majorities believe that the spread of charter schools has had a positive impact.

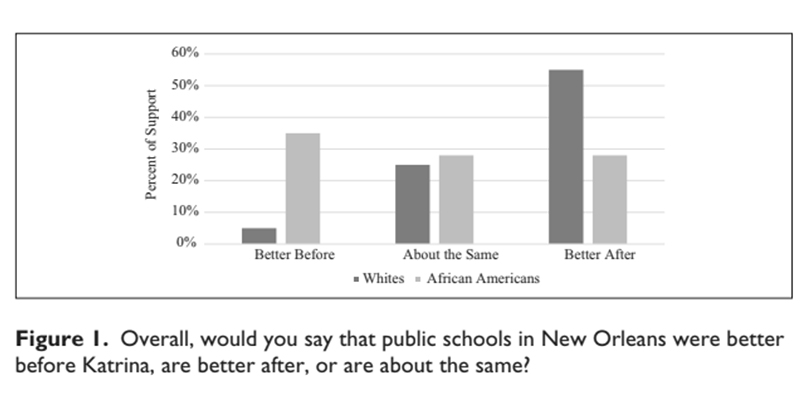

But in the paper, Morel and co-author Sally Nuamah, a professor at Northwestern University, point to significant differences in the way the post-Katrina reforms have been received by whites and blacks. Examining Cowen Institute polls from 2011 and 2013, he finds that black respondents were vastly more likely than whites to say that New Orleans schools were better in the period before Katrina; a majority said that they had either gotten worse or stayed the same in recent years. At the same time, a majority of white New Orleanians said they believed the schools had improved.

Black respondents were also much more likely to say they supported an end to the Recovery School District — the state-created entity that administered most schools after the storm — and a return of the schools to local control.

The divergent attitudes are the result of the black community’s loss of control over schools, Morel argues: Whereas previously the public school system (the population of which is estimated to be 80 percent black) was governed by a majority-black school board and staffed by mostly black teachers, the education regime following Katrina was quite different: Louisiana state officials, authorities at the RSD and charter school boards, who were all disproportionately white. By one estimate, the number of black teachers as a percentage of the whole decreased from 75 percent to 50 percent.

“The potential political power that Black citizens have as the majority in the city is negated,” the authors write, “as governance authority has shifted to the state level and to the charter boards, where Blacks do not constitute the majority. In other words, the traditional mechanisms of political power … have been circumvented by state-led governance as well as charter board governance.”

The departure of notable black figures from the local education scene has been the object of furor over the past decade. In the wake of the hurricane, more than 4,000 teachers were laid off from the school district — many of them black, and familiar to local families. Studies conducted since have shown that most never returned to teach in New Orleans.

Ashana Bigard, a prominent parent activist who has been sharply critical of the reforms implemented by the RSD, disagreed with the idea that top-level political changes had fueled black parents’ dissatisfaction, arguing that they were instead skeptical of shifts in school practice. She said she was more appalled by cuts to school music programs and the institution of “no-excuses” practices, like silent lunches, than by the local school board being sidelined.

“Black parents are upset because their children are getting horrible-quality schools, not because black people aren’t in charge,” she said. “Let’s be crystal clear: If you treat my child right, and my child gets a quality education, I don’t care if you’re purple.”

Still, she said, the mass layoffs “affected [families’] relationships with teachers.” She described feeling outraged after walking into a post-Katrina school to discover no teachers who were black or native to New Orleans.

“Everybody in the school was from someplace else — they were all young, white and shiny. What message does that send to children? I walk into school and you tell me I can go to college and be successful, but there’s no one who looks or sounds like me in this school? Obviously, that’s a lie; it’s not your values. If your values are black people in a black community, why wouldn’t you hire black people from that community?”

The cost of mistrust

The question of whether race has colored the perception of power in major cities like New Orleans is not a new one. Political scientists have long studied the ways that personal traits change how government is perceived.

Jeffrey W. Koch, a professor of political science at SUNY Geneseo, has found that members of various ethnic groups are all about as likely to say they trust the government in the abstract. But introducing race as an identity marker changes the equation: Blacks are significantly less likely to place their faith in government officials who are white.

“[People] tend to make that inference: ‘If we share an important characteristic — geography or partisanship or race — we probably have the same interests and preferences; if we don’t, it’s probably different,’” he said. “That’s consistent with what we find in all kinds of research. For ethinic minorities, they’re generally seeing people not of their race in positions of authority, so they could make the assumption that they’re not going to act in a way that’s consistent with their interests and preferences. But that’s true not only of ethnic minorities but also of whites.”

Changing racial power structures would therefore go a long way toward explaining the views of black New Orleanians toward a school system that became, seemingly overnight, vastly more white-led in both classrooms and boardrooms.

Still, Koch noted, school takeovers are never likely to be warmly received. Local control is a core value of education in the United States, and residents of a tight-knit community like New Orleans might simply resent having an important social service usurped from them for over a decade, regardless of any perceived shift in racial influence.

“Generally, outsiders coming in and taking over is not really popular, he said. “There’s going to be some pushback against the loss of local control anywhere, particularly in education. The United States has had local control in education for a long time. And because many people have kids in a local school, or know someone who does, it’s going to be a particularly salient issue for them.”

And there are limits to the extent of political distrust that can be attributed to race.

As a case in point: Perhaps no figure is as emblematic of the new New Orleans as Landrieu, the two-term mayor who was elected in 2010 and served as the city’s first white leader in 32 years. Landrieu presided over an era of massive change, including a sweeping return of private capital that many feared would bring about gentrification, as well as a wholesale reassessment of racial discrimination in the city’s law enforcement. But while opinions on Landrieu’s tenure were polarized by race, it wasn’t in the direction a political scientist might predict: Polling showed that the Democratic mayor was vastly more popular with black residents than white ones, perhaps as a result of his high-profile stance in favor of removing monuments to prominent Confederates.

Morel said the full impact of the post-Katrina education reforms has yet to be determined and that he hoped to examine changing opinions throughout the city on a variety of social services as time passed. But he added that the top-down method by which the reforms were achieved would impose a cost.

“We still have a lot of learning to do about how these reforms have affected outcomes in New Orleans,” he said. “But the thing that is not ambiguous is the political cost of this for the black community in New Orleans. If we’re interested in improving schools, in developing not only better test scores but citizenship, is this what we need to have? Do we need to essentially disempower an entire community to be able to say, ‘Graduation rates have increased by three or four percentage points?’ I think we need to dig into that.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly attributed a quote from a Wall Street Journal headline to Louisiana Superintendent John White.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)