Report: When Black Students and White Students Fight, Blacks Receive Harsher Punishments

Students who are black or poor are suspended at much higher rates than those who are white or affluent, according to a new study of school discipline trends in Louisiana. Even in specific fights that involve one black student and one white student, the black student typically receives a slightly more severe penalty.

The study and accompanying policy brief, both published by Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance for New Orleans, examined data from over 1 million disciplinary incidents logged between the 2000–01 and 2013–14 school years. It contributes to the growing body of research suggesting that intentional or inadvertent biases result in harsher punishments for minority children.

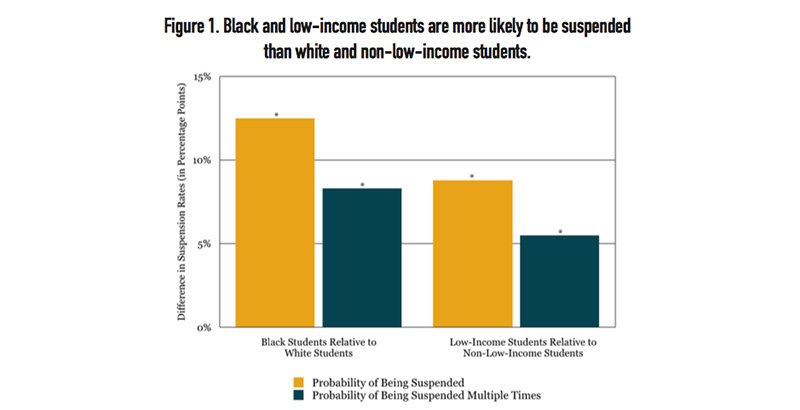

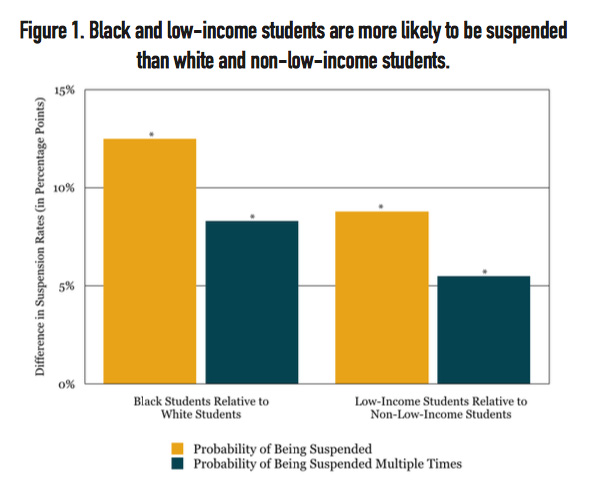

On average, black students were twice as likely as whites to be suspended for a behavioral infraction over the course of a school year, while low-income students were suspended about 1.75 times as often as more affluent ones. Both black and low-income students were also more likely to be suspended multiple times during a given year, with the disparities evident for both violent and nonviolent infractions.

The study was released at a moment of flux in the national conversation around exclusionary discipline practices like out-of-school suspension. This month, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos heard from educators who voiced reservations about Obama-era policies advising schools to examine their discipline policies. Some have claimed that the move to curb suspensions and address what activists call the “school-to-prison pipeline” has resulted in ungovernable schools where kids don’t always feel safe.

Even with the benefit of nearly 15 years of data, the research team issued a caveat on the difficulties of drawing conclusions around disparate impact. Discipline statistics rely on behavioral reports submitted by schools. Without observing individual behaviors, the authors warn, it is difficult to determine whether certain groups receive preferential treatment.

And yet some figures, drawn from incidents involving participants from different groups, draw a clearer picture, the authors found.

In fights involving one black student and one white student, the difference in punishment was smaller but still statistically significant: Black students are given a slightly longer suspension than whites involved in the same fight — about one extra day out of school for every 20 such incidents.

“While the magnitude of the difference may appear small in isolation, interpreting this finding is still challenging,” the authors write. “This analysis is still vulnerable to the possibility that black and white students behaved differently in these fights — and therefore warranted different punishments. However, we believe this analysis provides the most credible look in our data at whether discriminatory practices exist.”

The authors note that the data at the heart of their study shouldn’t yield blanket inferences about the prevalence of racial and socioeconomic discrimination in K-12 schools — only a look at the outcomes of interracial fights. But if well-reported interracial fights are shown to yield disproportionate punishments for minority students, it could indicate more evidence of prejudice in other areas.

“Given that we find that direct discrimination occurs in this context, with a black and white student receiving different punishments for the same exact incident, it seems likely that direct discrimination would occur where discipline disparities are less visible,” they conclude.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)