Report: Few Black and Latino Children Are Served by High-Quality State Preschool Programs

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

Just 1 percent of Latino children and 4 percent of black children are enrolled in high-quality state preschool programs, according to a report released on Wednesday that details the barriers students of color face when accessing early education.

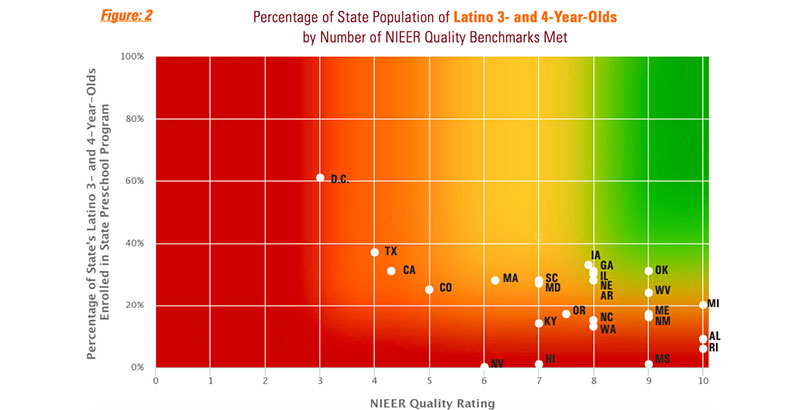

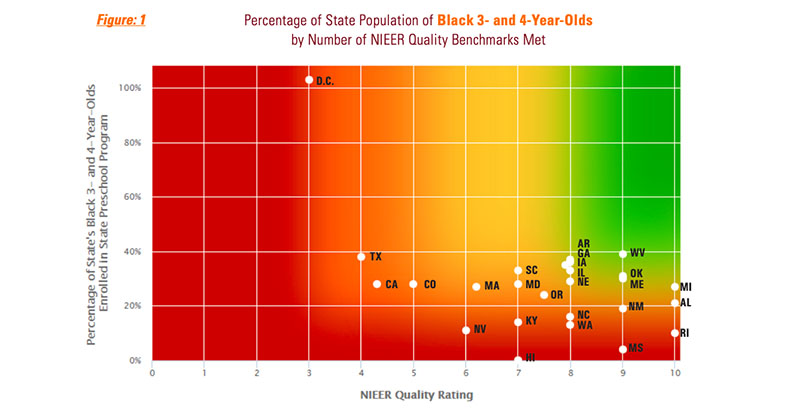

That finding, in a report by The Education Trust, centers on 3- and 4-year olds in state-funded preschool programs across 25 states and Washington, D.C. Of the states analyzed, none provided black and Latino children with sufficient access to high-quality programs, according to the Washington-based think tank, which focuses on education equity.

Researchers compared 2017-18 enrollment data for state-funded programs against 10 quality benchmarks set by the National Institute for Early Education Research, including hiring teachers with at least a bachelor’s degree, offering professional development and maintaining a staff-teacher ratio of 1-to-10. Researchers gave programs high marks if they met 9 or 10 of the benchmarks.

In 11 of the 25 states and Washington, D.C., Latino children were underrepresented in programs relative to their overall population numbers, and black children in three states were similarly underrepresented.

Although the report doesn’t compare their access to children from other races and ethnicities, it argues that the focus on black and Latino children is important because they face additional barriers to education.

“Systemic racism causes opportunity gaps for black and Latino children that begin early — even prenatally, which makes it crucial for these families to have access to high-quality [early childhood education] opportunities as a pathway to success into their K-12 education,” according to the report. “Without these opportunities, black and Latino families are left to do even more work to overcome the barriers they face” in K-12 schools.

State preschools are just one of many early childhood options for young children, in addition to private schools and federal Head Start programs that are not substantially supplemented or administered by states. Researchers centered the report on state programs because half the states in the country provided adequate racial demographic data. Also, “policymakers actually have the power and authority to make changes” in state programs, said report author Carrie Gillispie, a senior analyst on The Education Trust’s P-12 policy team.

The quality of preschool programs, and access to them, varied significantly across the 25 states and Washington, D.C. In fact, researchers discovered a sort of seesaw pattern to the data: As access for black and Latino children improved, quality diminished, but as program quality improved, fewer black and Latino children were represented. Though Mississippi’s state preschool program met nine of the national institute’s quality benchmarks, for example, it served just 4 percent of black children and 1 percent of Latino children. The opposite is true in Washington, D.C., where a program that met just three of the benchmarks served a majority of the region’s black and Latino children.

Gillispie said the problem could be straightforward: States lack adequate funding to improve program quality while promoting access. That dynamic “makes sense logistically but is not acceptable in terms of equity,” she said. “While it’s great that D.C. has really high access, particularly for black 3- and 4-year-olds, it’s just not acceptable that its quality is so low.”

In some states, such as Michigan and Rhode Island, access to preschool is limited to 4-year-olds. Nationally, about a third of 4-year-olds and just 6 percent of 3-year-olds are enrolled in state preschool programs. States should enroll 3-year-olds, the report argues, because both years are “highly sensitive periods of brain development and learning that build on one another toward a strong start in kindergarten and beyond.”

To improve both access and quality, the report offered nearly a dozen recommendations. Policymakers should meet the national institute benchmarks, the report said, and should make enrollment easier — for instance, by providing materials in multiple languages. Because black and Latino parents are more likely to have jobs with inflexible and unpredictable work schedules, preschool hours and locations should better align with their needs, the report argues.

“First and foremost, policymakers have to invite conversations with black and Latino communities [and] listen to their needs,” Gillispie said. “Invite them to the table before policies are changed or before policies are made so that black and Latino communities are really informing policies.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)