Reliving Katrina 12 Years Later as Harvey Hit Houston and NOLA Educators Planned on Repaying an Old Debt

New Orleans

They call them ghosts in the classroom, the experiences teachers, parents and children carry, albeit subconsciously, when they show up at school. In the most prosperous, intact communities, the specters are deeply rooted beliefs arising from the ways the adults were parented and taught.

In other places, where tragedy, poverty and violence compound the challenges schools are asked to confront, trauma’s aftereffects can haunt every aspect of the day. Everything that transpires within, from the decibel of adult voices to the collective response to rage, requires recalibrating.

It wasn’t easy to get folks in New Orleans to focus on the quotidian last week. Not only was Tuesday the 12th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, Harvey had been lashing the coast of Texas for five days. Whatever the intended topic, conversations inevitably touched on where people rode out the first storm and how they planned to help in the wake of the second.

Because a quarter of a million New Orleans residents fled to Houston after Katrina and an estimated 100,000 stayed there, almost everyone felt some connection to the city. Heightening anxieties, in early August when 10 inches of rain fell in the space of three hours, swaths of New Orleans flooded, partly because the ancient turbines that run the pumps that move rainwater were broken, the outcome of neglect.

Sandbags were still stacked neatly along the foundations of the restored shotgun houses in the neighborhoods along Bayou St. John last week and the residents of Mid-City, which suffered the worst of the recent damage, are still waiting on insurance settlements to replace hundreds of cars. Umbrage over storm-drain officials’ empty promises has yet to fade.

Who knew what another downpour would bring and what public official wanted to be the authority who failed to err on the side of caution? As Harvey pelted Louisiana with rain and wind Aug. 29, New Orleans schools closed for the day. Mayor Mitch Landrieu urged Crescent City residents to stay home if at all possible.

The anniversary passed without incident, but when schools reopened the following day everyone was thinking about floodwaters — how the barriers and conduits that manage them interact and how familiar the dominoes toppling in Houston seemed.

At the end of the day, a school is a community in which, ideally, children, parents and teachers pull together in pursuit of a healthy tomorrow. As they attempted to go about their business, New Orleans educators were painfully aware that reconstructing those communities can take far, far longer than re-opening flooded buildings.

In a meticulous conference room at Educare New Orleans, an early childhood education center located on the former site of the St. Bernard Projects, a notorious public housing complex, Angelique Shorty-Belisle and Keith Liederman traded Katrina memories.

Liederman is the CEO of Kingsley House, the oldest Settlement House in the South, which operates Educare among other programs. When Katrina hit, he evacuated, first to Houston and then to Atlanta, where his family stayed for five weeks. After the 2005 storm, New Orleans educators got advice and support from early childhood leaders in New York City, who had tended to families that survived 9/11.

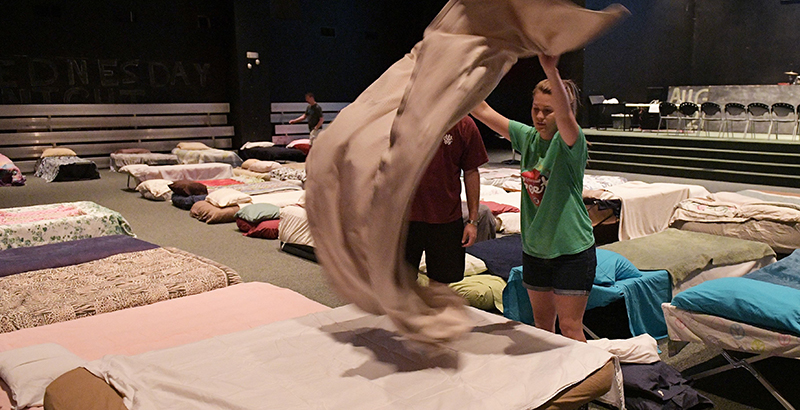

Uniquely positioned to understand both the trauma and the practical challenges 12 years later, Educare leaders pitched in in the wake of Harvey-related floods in Baton Rouge and Cedar Rapids. There was nothing to be done to help Houston until the waters receded, but Liederman and his colleagues were already thinking about their Texan neighbors’ needs.

At Pressed, the coffee shop in the Greater New Orleans Foundation building, a mound of diapers and cleaning supplies took over a wall by the front door. At the Bayou Beer Garden — where a patron in a kayak was photographed buying a drink during the local flood three weeks ago — a jar of cash bore a sign: “So people can buy their own underwear and shit.”

Located northeast of Corpus Christi, Texas, Aransas County Independent School District announced schools would be closed indefinitely and advised families to go ahead and enroll their children in the districts to which they had evacuated. All told, more than 200 Texas districts and charter schools delayed opening.

After Katrina, the KIPP network of public charter schools set up a school in Houston specifically for children from New Orleans called KIPP New Orleans West College Prep. With the assessment of the damage to Houston’s schools only beginning, participants in the reconstruction of New Orleans’ education landscape were already organizing reciprocal efforts.

Twelve years ago, the crime-ridden St. Bernard Projects where Educare is now located were under 8 to 15 feet of water. The centerpiece of a new mixed-income neighborhood, the gleaming preschool incorporates some of the walls of the housing project.

The teachers and aides who work within the reconditioned brick corridors—brightly painted mullions dividing the sunshine that pours through the windows—have special training in supporting the tiniest trauma survivors.

Shorty-Belisle, Educare’s school director, rode out Katrina in Monroe, Louisiana, with family, and Tuesday’s anniversary on the Mississippi coast. Back at work, she gazed across a vacant field awaiting further redevelopment in the direction of the elementary school, long since razed, where she used to teach.

She pointed to a new brick building a few hundred feet away that would soon house a health clinic; the facility hadn’t yet moved out of its post-storm trailer located next door. There’s a new high school a few blocks away but the elementary school has yet to be replaced.

Educators in Houston, Shorty-Belisle said quietly, likely can’t yet imagine how long a slog recovery will be.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)