Reducing Class Sizes Is Popular With Parents but Not Education Experts. New Research on CA Program Might Change That

Lowering class sizes for elementary students in California — a controversial move that has received a lukewarm reception in some prominent research studies — resulted in greater learning gains than previously thought, according to a new study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research. In addition to the positive impact of studying in smaller groups, students benefited from the migration of new classmates who were drawn in from area private schools by the promise of a lower student-teacher ratio.

The paper, written by economists at Duke, New York University, and the University of Toronto, examines the effects of California’s effort in the mid-1990s to cut class sizes in grades K-3 to 20 from a statewide average of 28.5. The initiative was one of several inspired by Tennessee’s enormously influential Project STAR, which bolstered academic achievement in the state by reducing class sizes in the lower grades.

Such efforts tend to be popular with both parents and teachers, but they are regarded somewhat skeptically by education policy experts, who often point to higher average class sizes in academic superstar countries like Japan and Korea and argue that the resources dedicated toward hiring more teachers could be put to better use elsewhere. Indeed, alternative investments like nurse home visits to first-time mothers and expanded pre-K access are routinely compared to class-size reduction (CSR) and found to yield greater improvements in student achievement at a fraction of the price.

California’s 1990s-era class size reduction mandate is my go-to example of how easily happy-sounding school reforms can go wrong at scale. This new paper suggests its effects were more positive than I’d imagined. https://t.co/7MdcsrqIZR

— Thad Domina (@ThadDomina) January 8, 2018

Class size reduction in California had pretty decent positive and sustained effects on student achievement (this *certainly* runs counter to the dominant narrative on this policy in CA). https://t.co/1LXuiI3ziH

— Morgan Polikoff (@mpolikoff) January 8, 2018

The paper’s authors acknowledge the high dollar value of California’s reform ($650 per student provided by then-Gov. Pete Wilson, enough to entice almost every school district in the state) but maintain that the policy’s most striking benefits lay in changing the demographics of many public elementary schools across the state. Specifically, students who would have otherwise attended private schools — and who in many cases transferred to private schools in subsequent years of schooling — attended public schools from kindergarten through third grade.

The onset of CSR coincided with “sizable reductions” in private school enrollment across California, they write. Before 1996, when the policy was enacted, the statewide private school share was 9.9 percent; after reducing class sizes, it fell to just 8.4 percent. There was also a steep drop in the number of private schools per capita compared with the rest of the United States.

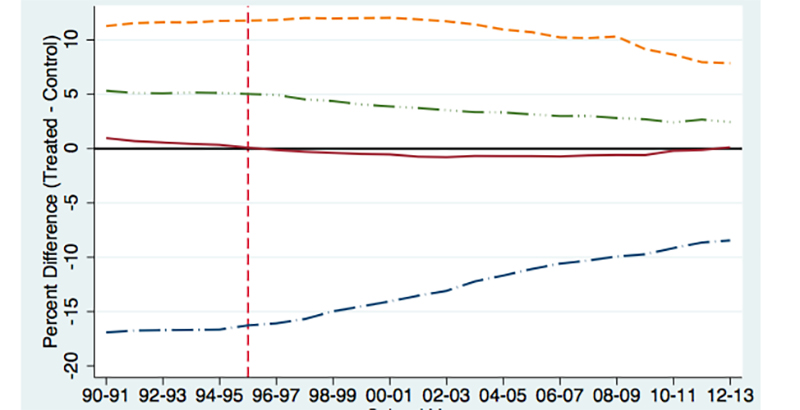

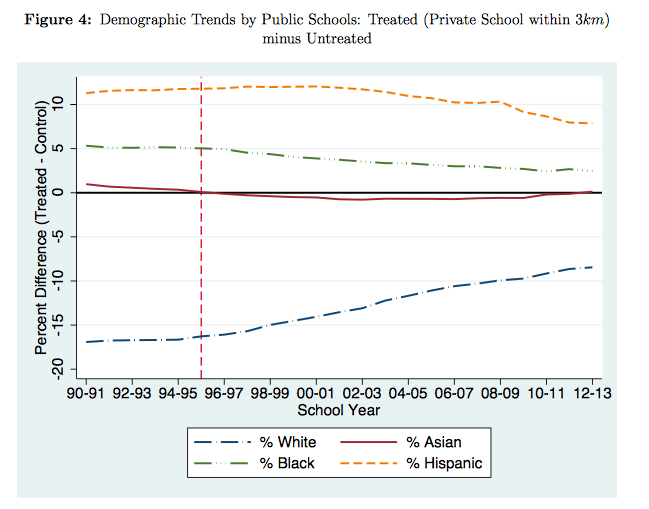

The flow of would-be private school students into public elementary schools resulted in a swift demographic change in classrooms, which suddenly welcomed thousands of whiter, more affluent students. Their presence resulted in higher average test scores, but also helped improve their classmates’ performance as well, the authors said.

The perceived advantage of attending schools with lower student-teacher ratios led to greater demand for public school seats during the years CSR was being rolled out. In districts that succeeded in lowering their class sizes, the researchers found that home prices shot up by as much as 2.6 percent, reflecting the newfound desirability of sending kids to public schools.

Another finding of note: The abrupt hiring surge that accompanied the program — smaller classes require more teachers, after all — correlated with small declines in learning among students who were assigned to newer teachers, who were often less experienced and possessed fewer credentials than existing ones.

In an email, Sarah Woulfin, an assistant professor of education at the University of Connecticut who was hired as a California teacher with an emergency credential in 2000 to help combat the shortage of instructors, told The 74 that she believed more could be done to help educators exploit the possibilities of lower class sizes.

“To increase teacher quality, it is important for district and school leaders to think carefully about how to leverage teacher leaders and coaches and how to align professional development opportunities so that teachers have the capacity to fully enact CSR,” she wrote. “In particular, experienced and exemplary teachers, as well as instructional coaches, could deliver targeted support to both new and experienced teachers on how to capitalize on smaller class sizes.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)