Post-Parkland Memo: As Broward Schools and Other Districts Limit Building Access to a ‘Single Point of Entry,’ Experts Warn the Move Isn’t a Quick Fix

When students in Florida’s Broward County returned to classes in August, they arrived to heightened security designed to keep children safe from the kind of attack that left 17 dead at a district school last February: thousands of new surveillance cameras, more school-based police, and a promise of increased safety drills.

But arguably the most visible security measure is a push to retrofit each campus with a single point of entry. In Broward County schools, a series of gates and checkpoints funnel visitors to a single entryway leading to a “welcome center.” All other entrances to school buildings remain locked for a bulk of the school day.

It’s a strategy that the Broward County school district has been rolling out for years, but the Valentine’s Day slaying at Parkland’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School gave the project fresh urgency. This school year, 135 of the district’s 230 campuses resumed classes with single points of entry in place, with the remaining buildings scheduled to implement the strategy by next year.

While districts across the country have implemented single points of entry on their campuses in recent years, the strategy received renewed attention following a spate of high-profile school shootings in 2018.

The strategy, largely embraced by security officials, demonstrates how even the simplest security techniques can draw controversy amid the contentious national debate over how best to keep students safe. By limiting access points into a school, proponents say, school officials can effectively screen visitors and identify potential threats. But critics say the technique is cumbersome for students and parents, can cost districts millions of dollars to implement, and is simply impractical for some districts.

In order to be effective, experts say, the effects of reducing entry points must be part of a larger security strategy.

“It is too easy a fix to say, ‘Let’s just have students enter a single point of entry into a school and then we’ll all be safe,’” said JoAnn Bartoletti, executive director of the National Association of Secondary School Principals. “There is just no way to guarantee that hardened exteriors of schools is the way to keep out those that are unwanted.”

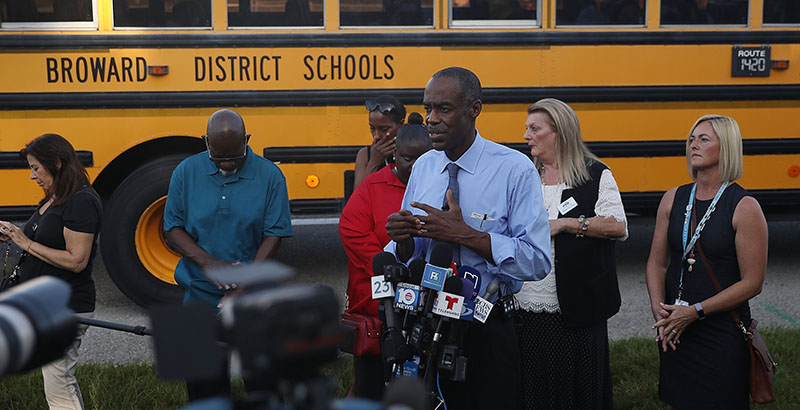

In Broward, Superintendent Robert Runcie showed off newly installed entry features at the school during a July media event at Miramar High School, part of a $26 million project to install single entryways at all campuses, paid for through a 2014 bond initiative. Installed over the summer, the school’s new entry process includes a series of fences and gates that remain locked for the bulk of the school day, and exterior school doors that automatically lock from the outside. In order to facilitate the smooth arrival and dismissal of students, the gates are left unlocked for a brief period in the morning and afternoon.

To enter a campus with a single entrypoint — which the district anticipates will be installed in all schools by early 2019 — visitors must present photo identification to security staff at the front gate to the campus. Then, they’re directed to the school office, where they undergo another ID check. Throughout the day, students and visitors are required to wear identification badges. While some in the community have called the new procedures daunting, others say district efforts have lagged since the February shooting, prompting criticism when plans to install metal detectors at Stoneman Douglas were delayed.

During the July press event, Runcie acknowledged that the single-point-of-entry system is cumbersome, but he said the district wants to “meet and exceed our community’s expectations of what security should look like on our campuses.”

“There’s no way that we’re going to implement security measures that this community expects from us and not inconvenience students, not inconvenience visitors and folks in the community,” Runcie said. “It’s going to happen. It’s going to be the new normal, and folks are going to have to adjust to it.”

At Stoneman Douglas, the district invested $6.5 million in enhancements this year, including more than a dozen safety monitors, new locks on classroom doors, upgraded video surveillance, and new gates and fences.

But the Parkland campus already had a single point of entry during the Valentine’s Day shooting, and it appears the shooter exploited the process. Similar to the protocol in place this year, campus gates were unlocked near the end of the school day to allow a smooth dismissal — reportedly affording the gunman a window to act. But district officials say additional school security staff and student identification badges will help ensure security during arrival and dismissal times, according to the South Florida Sun Sentinel.

Broward County school officials didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Karina Ruiz, principal at Oregon-based BRIC Architecture, has been designing school buildings for more than two decades and supports districts that choose to implement single entry points. The system adds a layer of security to campus buildings, but she cautioned that this strategy alone won’t keep students safe from all threats. Installing equipment to “harden” campuses, she said, is akin to treating the symptoms of a disease rather than treating the root cause of the illness.

In a recent op-ed, Ruiz said school leaders are asking architects to equip their buildings with a range of security features, such as bullet-resistant glass, security entry vestibules, and surveillance cameras. But school security should also focus on reducing social isolation, depression, and discrimination, wrote Ruiz, incoming chair of the American Institute of Architects’ committee on architecture for education.

School architects, she wrote, have a responsibility “to serve as a counterpoint to some of these hardening tactics. We cannot let fear dictate design or advocate for designing our schools to resemble prisons.”

Kenneth Trump, president of National School Safety and Security Services, offered a similar take. Trump said he recommends that schools install single entry points, which help with visitor management. But he said the system isn’t foolproof and can be more difficult to implement in southern states like Florida, where schools often occupy sprawling campuses with multiple buildings. To bypass the system, he said, intruders could prop open other doors or toss a weapon over a perimeter fence. Additionally, he said districts should factor in how a hardened campus perimeter might affect other security features, such as the need for emergency responders to have easy access to campus.

“A fence is certainly a deterrent to those who can be deterred and a delay to those who can’t,” said Trump, who has no relation to the president. “It shouldn’t be looked at as a guarantee or a panacea, but it’s an extra tool.”

While the effort to harden campus perimeters is the least controversial option among school security practices, Bartoletti, of the secondary school principals association, said it is cost-prohibitive for some districts and is, on its own, insufficient.

A former high school principal in New Jersey, Bartoletti said the school she oversaw had 23 separate entrances. Rather than trying to create a single point of entry, she said, schools should put greater emphasis on training so leaders know how to identify people who don’t belong.

“What I find so interesting about the people who suggest these kinds of solutions for schools is their failure to understand the population of the school, and somewhat the culture of the school,” she said, adding that as principal “there was not a given day that I walked around that school that I didn’t find numerous doors propped open or a twig or a stone or something put in the door so that kids could get in and out of the school.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)