Newark Students, Including Special Needs and English Learners, Are Less Likely to Transfer Out of Charters than District Schools, Study Finds

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

Students who attend charter schools in Newark, including English learners and those with learning disabilities, are less likely to transfer out within two years than their peers at the district’s public schools, according to a new study. Children were also significantly more likely to shed their special-needs classification while enrolled at a Newark charter, the authors note.

The study, released as a working paper this week and summarized in the journal Education Next, offers more perspective on the long-running debate over admissions and retention in the charter sector. Critics of the publicly funded but privately operated schools have alleged that they push out kids with learning, language or behavioral challenges by means of tough disciplinary tools like suspension or expulsion.

Co-author Marcus Winters, a professor of educational leadership and policy studies at Boston University, said in an interview that he believed individual schools of all kinds “inappropriately” encouraged some students to leave. But the Newark study, along with earlier research looking at schools in Tennessee and North Carolina, has disproven the notion that charters routinely engage in the practice, he argued.

“I do think it’s fair to say that our paper … has now sufficiently debunked the myth that charter schools — at least in these areas that have been studied — are systematically pushing these students out,” Winters said.

Winters and co-author Allison Gilmour, a professor at Temple University, set out to compare enrollment trends in Newark, a city with one of the largest charter school sectors in the country. To do so, they used data from the Newark Enrolls assignment system, which allows families to select among their choice of traditional schools and approximately 70 percent of the city’s charters. (Not all local charters participate in Newark Enrolls, but those that do account for about five-sixths of charter students.)

Several variables in the Newark Enrolls formula determine which students are assigned to certain schools, including each child’s rank-ordered school preferences; individual factors prioritized by various schools (such as sibling preference); and randomized lottery numbers that are used in case a given school is overenrolled. By gathering administrative data between the 2014-15 and 2017-18 school years, Winters and Gilmour were able to compare patterns of school entrance and exit for nearly 14,000 students.

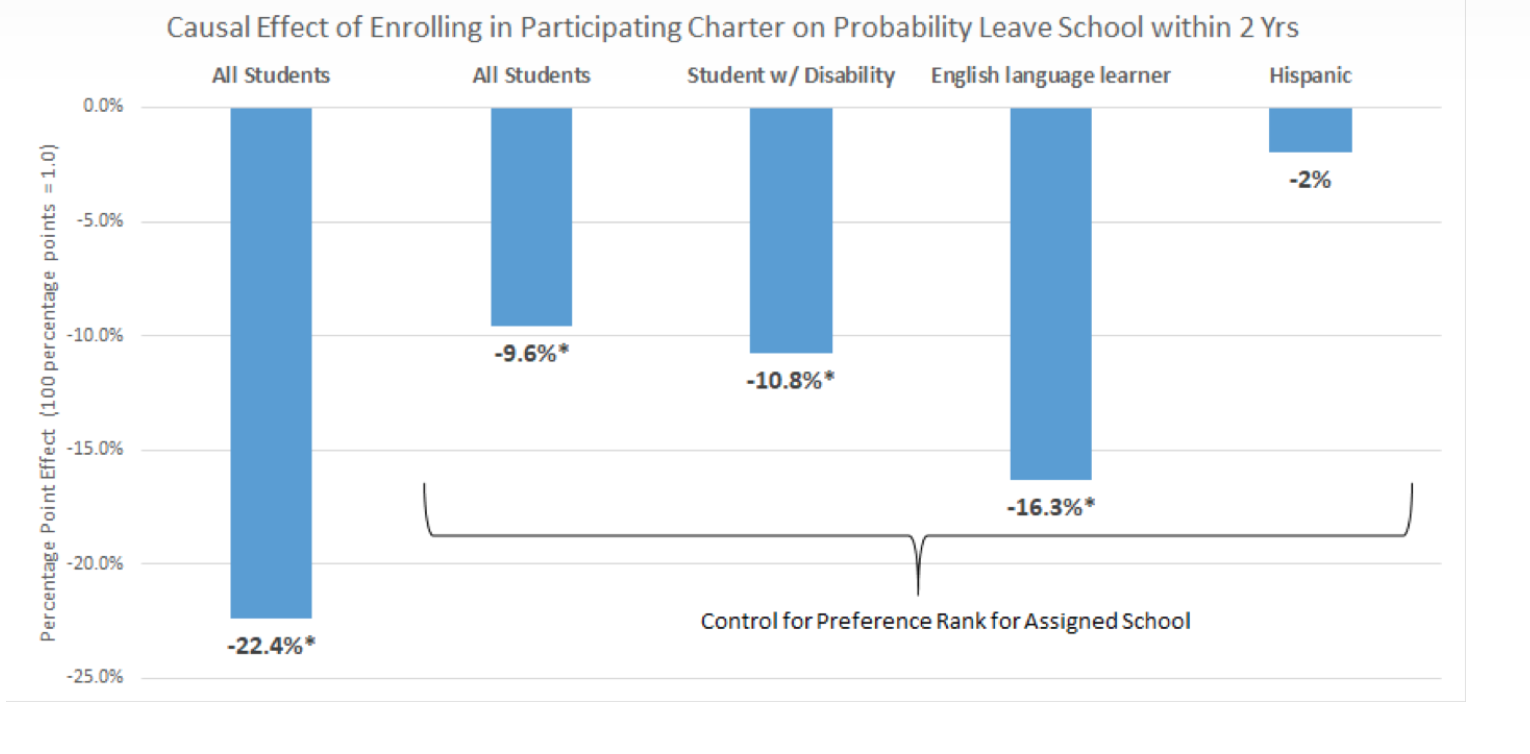

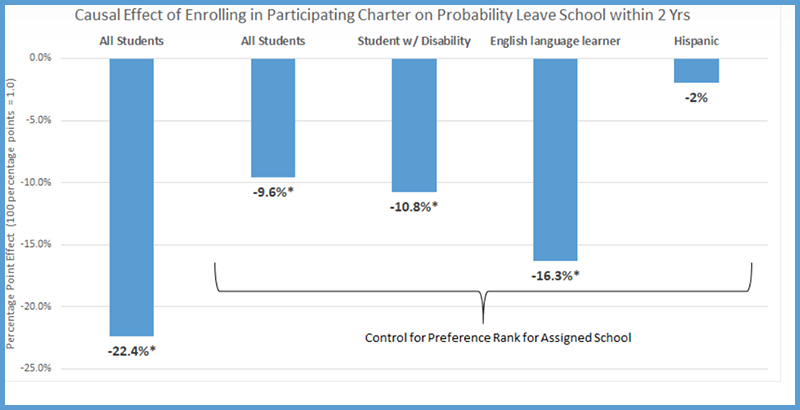

In all, children attending Newark charter schools were 22 percentage points less likely to leave that school within two years than substantially similar students who were instead assigned to traditional public schools. English learners were 16 percentage points less likely to transfer out of a charter, and students with a disability nearly 11 percentage points less likely. The difference for Hispanic students was not statistically significant.

The smaller chances of transfers may be attributable to the system’s format of ranked school preferences. In a model that controlled for families’ ranking of schools, charter students were still less likely to leave within two years, but only by about 10 percentage points; that suggests that a sizable portion of the charter school effect is simply a reflection of students attending the school they wanted to go to in the first place, Winters said.

“You might just be more willing to stick it out with a school that you originally had as a higher preference,” he said. “If you’re attending a school that you went to on purpose, you’re just less likely to leave it. And if you’re going to a charter school in a place like Newark, where several of the charter schools are among the most popular choices … you’re probably going to one of your most highly preferred schools.”

By tracking the same students over time, the study also observes gradual movement within individual subgroups. Specifically, children with a special-needs classification at charter schools are much less likely to still have an Individualized Education Program a few years later — a phenomenon that may help explain why the percentage of students receiving services is lower in charters. The effect is particularly notable for children entering charter schools between kindergarten and third grade (31 percentage points more likely to lose a special-needs classification within three years) and between grades four and six (20 points). Those findings dovetail with research pointing to similar trends in special-needs assignment at Boston charter schools.

Comprehensive examinations, including a 2012 report from the federal Government Accountability Office, have shown that charters generally teach smaller numbers of kids with disabilities than district schools. More recent evidence indicates that those gaps may be shrinking, though it’s unknown how the huge upheaval triggered by COVID-19 may have shuffled enrollment trends.

If the study raises doubts about the claim that charter schools consistently work to remove struggling or hard-to-teach students from their classrooms, it offers little clarity about how they approach recruitment. At least one study has found that charters in multiple states were less likely than district schools to respond to application inquiries from parents of children with severe disabilities.

Winters concluded that the population differences between sectors could arise from only one of three sources: recruitment of students, mobility of students once enrolled and (in the case of English learners and disabled students) changes in status classification such as those detected in the Newark study. More investigation was needed into how different schools attract families, he said.

“It’s clear to me, at least, that the major driver in these enrollment gaps is who’s enrolling in the first place. We need more information about the enrollment side.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)