New Report: Most States Lack Power to Merge Struggling Districts With Wealthy Neighbors, Leaving Poor Districts Stranded

For more than two decades, students at a small Pennsylvania school district loaded into school buses every morning for an eight-mile commute — to attend classes in another state. Midland’s school district fell into a financial decline after the local steel mill closed shop. With a withering tax base, the district’s entreaties to join forces with a better-off public school system right next door were rejected.

With few other options to escape and needing to slash costs, the district shuttered its high school and shuffled its students across the state line to a district in Ohio.

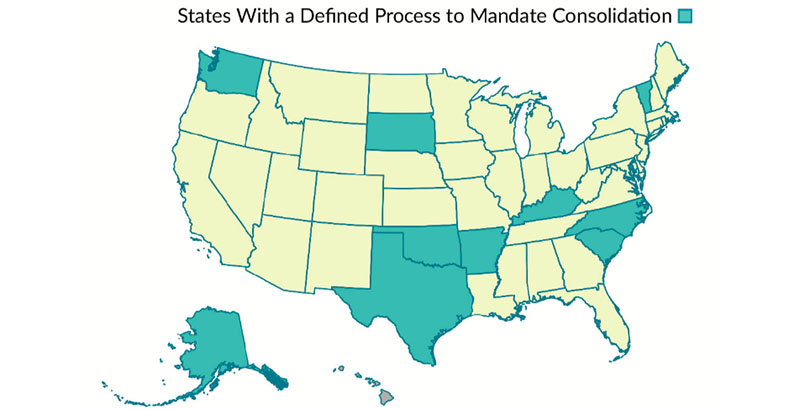

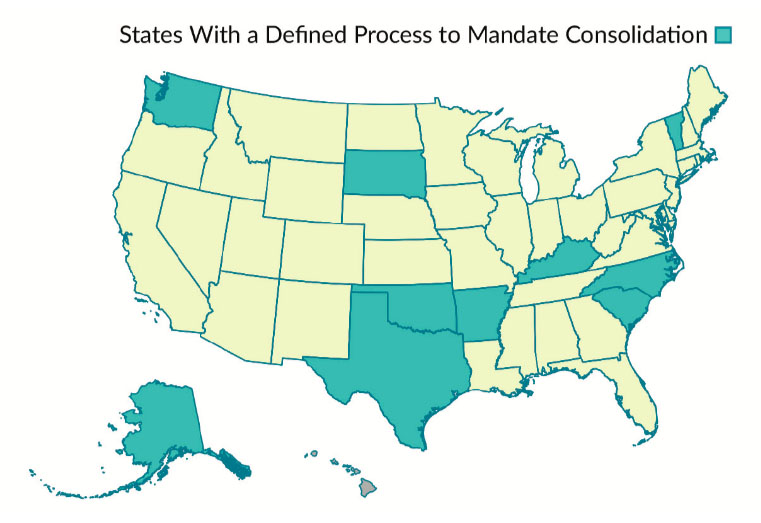

A report released Tuesday on school district consolidations highlights the roadblocks Midland and other financially fraught districts across the country face when school leaders try to merge with more stable neighboring districts. Lawmakers in nine states have granted a state-level entity authority to mandate school district consolidations under dire circumstances, while mergers remain voluntary in most parts of the country. The report was done by EdBuild, a nonprofit think tank that focuses on public school funding equity.

In states where consolidation is voluntary, however, community members and school leaders in wealthier school systems have few incentives to help out their struggling neighbors.

“By allowing our public education system to be separated into territories of haves and have-nots, we reproduce our wider social inequality in the schools that should be the opposite: The ladder that enables mobility, and greater equality for all,” according to the report. “Instead, we permit segregation to develop as the wealthy sort themselves into advantaged districts, leaving the needy behind.”

EdBuild puts the blame on the system employed in most U.S. states, which ties school funding revenue to local property taxes. Because district borders define both school assignments and property tax jurisdictions, wealthy systems benefit when they stay small. Local taxes account for nearly half of school funding nationally, and residents in more affluent communities benefit from district borders that exclude areas with lower property values and poorer residents. When well-off families buy into better-funded (and usually higher-achieving) districts, poverty is further concentrated.

“That locally rooted funding system that leaves poorer communities without the resources to self-fund, that same locally rooted funding system means that nobody else has the incentive to open their doors,” said Zahava Stadler, EdBuild’s policy director.

The EdBuild report traces the issue back to the 1940s, when Texas officials encouraged district mergers but the Edgewood Independent School District in San Antonio was repeatedly shut out, leaving students stranded in underfunded schools. The district sued, arguing that the state’s system of funding schools in part through local property taxes deprived low-income children of an education. The case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court; justices found in 1973 that the Constitution does not give the federal government authority to enforce state school-funding systems.

But constitutions in every state guarantee children a free public education. When state officials fail to step in and help cash-strapped districts, EdBuild researchers argue, they fail to uphold their state constitutional obligations to low-income children.

“One thing that they could do is to ensure that when a district becomes unsustainable within the borders that it has, that there’s a way to change those borders to give those students access to the resources that they need,” Stadler said.

Midland schools’ financial woes, which were highlighted in the EdBuild report, began in the 1980s when the steel mill, the town’s largest employer, shut down. As property values plummeted and residents fled, school leaders approached more than a dozen neighboring districts with hopes to merge. With no takers, the Midland district closed its high school in 1985 and, since then, has relied on patchwork tuition agreements to send students to nearby districts, including, until 2015, the one in Ohio. Today, Midland students attend charter schools or high schools in the neighboring Beaver Area School District.

Pennsylvania has long faced criticism over its funding system, and the commonwealth currently is defending itself against a lawsuit arguing that lawmakers failed to provide a “thorough and efficient” education system guaranteed by the constitution. Legislators updated the funding formula in 2016, but its effects are limited. EdBuild found 18 Pennsylvania districts that have sought to merge with neighboring systems since 2000, but only one succeeded, making it the commonwealth’s only merger since the 1960s.

“School funding is especially local in Pennsylvania, just because there’s a history of the state not doing as aggressive a job of compensating for those differences in local tax bases that we see in some other states,” Stadler said. “Pennsylvania has done quite a poor job of ensuring all its kids have access to an equally well-funded education.”

In the nine states that give lawmakers the option to initiate district mergers, authority differs. In North Carolina, for example, state education officials can merge districts for any reason, while officials in Oklahoma can only force district mergers when a system is struggling academically or ends up not operating any schools.

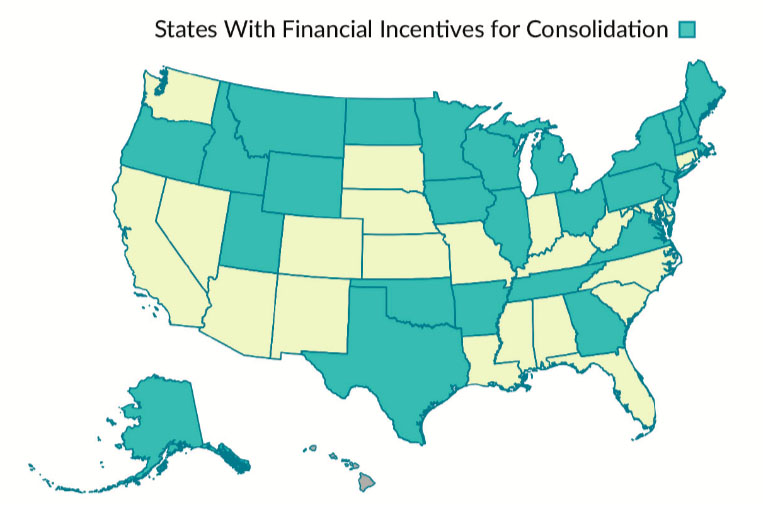

In 25 states, including New York and Texas, lawmakers can encourage district mergers through financial incentives, but EdBuild found that that’s rarely successful since the monetary enticements expire and often fail to offset the revenue losses brought by merging. Well-off districts, therefore, opt to keep to themselves.

Through the report, EdBuild aims to highlight strategies states can take to make schools more equitable between districts, Stadler said. Legislators could adopt laws that mandate consolidations when necessary, or they could take a more sweeping approach and distribute education funds centrally rather than relying on local property taxes.

The report is the group’s third in a series scrutinizing school district borders. The first report highlighted America’s most socioeconomically segregated school district borders, and the second delved into state laws that allow affluent communities to secede from school districts to create their own, wealthier systems.

The second report focused heavily on the community of Gardendale, Alabama, where the court found that now-defeated secession efforts were motivated by race.

School secessions and district consolidations, Stadler said, are “two sides of the same coin.” Alabama, for example, has a permissive secession policy but lacks authority to merge a school system should it fall into financial distress.

“If a town like Gardendale pulls away using the state’s very permissive laws and then the state begins to see deleterious effects on kids, it can’t do anything to put those districts back together,” Stadler said. “So once the districts break apart, there’s nothing the state can do to remedy the situation.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, and the Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to EdBuild and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)