This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new numbers, research, and reporting. Go Deeper: See our full series.

Most states don’t do nearly enough to ensure that new teachers actually understand literacy, according to new data from the National Council on Teacher Quality. Although teacher preparation programs often require instruction on what is called “the science of reading,” states do not require that teaching candidates demonstrate that knowledge, NCTQ finds.

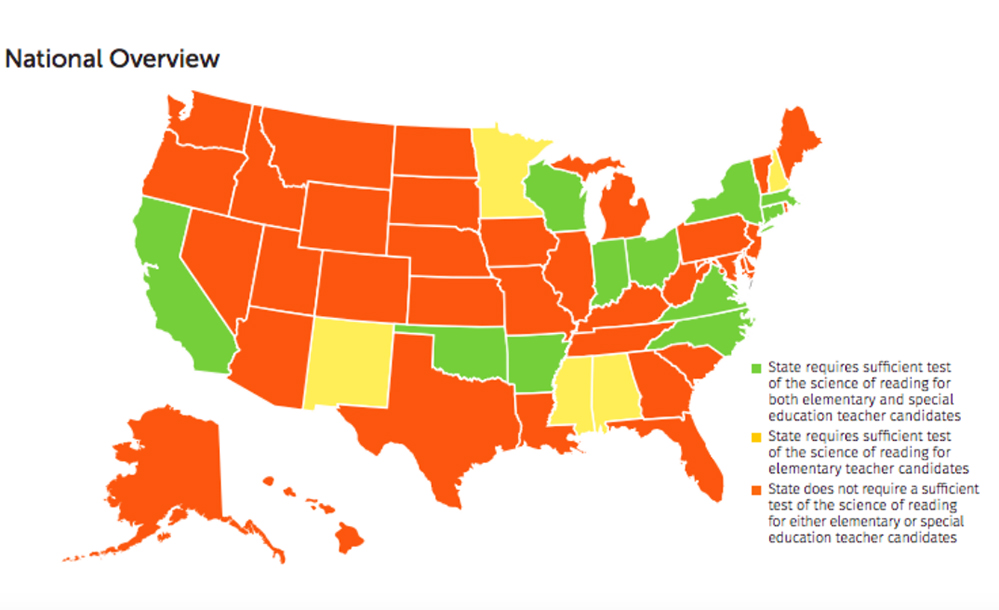

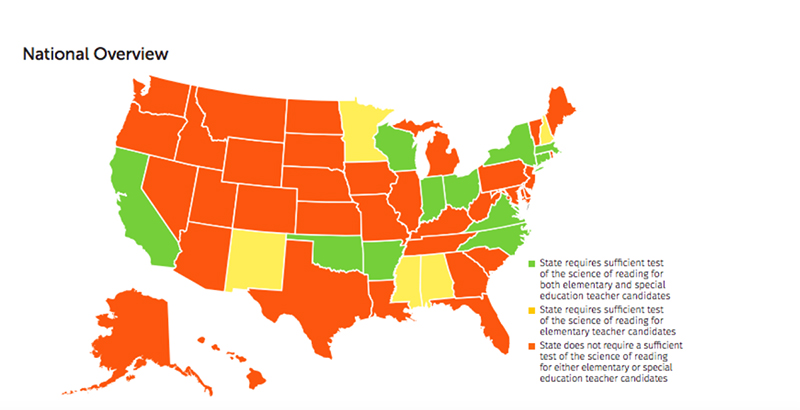

The report, written by NCTQ staffer Elizabeth Ross and released today, examines policies in all 50 states to assess the literacy knowledge of prospective elementary and special education teachers. In order to gain a teaching license, elementary teaching candidates in most states must pass a test on literacy knowledge. By contrast, 25 states and the District of Columbia do not require the passage of a reading test to become a special education instructor.

Ross told The 74 that all teachers in both disciplines should be schooled in, and tested on, what is called the “science of reading” — the broad body of research on brain organization and development that offers insights into how kids build reading skills. The report notes that even those states that directly link reading tests to licensure often don’t provide stand-alone assessments in the science of reading.

“It’s so important that both … elementary and special education teachers demonstrate this knowledge, and a strong research base exists around the importance of teachers knowing the science of reading when they’re teaching children how to read,” she said. “Elementary teachers, of course, are primarily responsible for teaching children to read, but research also demonstrates that more than 80 percent of students identified for special education services are identified based on reading difficulties.”

Much of the relevant literature on the science of reading was summarized in the highly influential 2000 report of the National Reading Panel. The body was convened in the late 1990s, in part to settle the contentious “reading wars” that raged over the importance of phonics instruction. The report addressed scientific research in five areas that are considered critical elements of scientifically based reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

To ensure that teachers have some degree of expertise in these subjects, NCTQ recommends that every state require that new teachers pass a test of literacy knowledge to attain a teaching license. Presently, only 11 states mandate such tests for both elementary and special education teachers: Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

NCTQ estimates that just 37 percent of all teacher preparation programs around the country provide instruction in scientifically based teaching methods. Experts on literacy, such as University of Wisconsin cognitive scientist Mark Seidenberg, claim that the science of reading too seldom filters down through teaching programs and into classrooms. As he explained in an interview with NPR earlier this year, “This basic science does not go into the preparation of teachers. More often they’re told it’s not really relevant, that the science is sterile and has no connection with what teachers do in the classroom.”

Ross maintains that the case is stronger than ever that teacher licensure be predicated on the demonstration of literacy knowledge. While it’s good that some teacher preparation programs offer coursework in the science of reading, instruction must be accompanied by state assessments, she said.

“We’ve found that standards alone are insufficient to ensure that teachers have demonstrated knowledge of the science of reading — and for folks who work in education, this shouldn’t be surprising to us,” she said. “When we think about student requirements at the state level, we have both standards — which set out what students should know and be able to do — but then also assessments to check that students have met those standards.”

But not all experts agree. In an email to The 74, Tim Shanahan, a professor emeritus of curriculum and instruction at the University of Illinois at Chicago who also served on the National Reading Panel, said that although he sympathized with the goal of improving reading instruction through better credentialing, he knew of no evidence linking performance on literacy tests to higher-quality teaching down the line.

Shanahan wrote that he believed such tests were reliable, but he added, “What’s unclear to me is whether the differences in knowledge measured in this way make any measurable difference in factors like: quality of leadership in a school, effectiveness in instruction, ability to evaluate students’ learning needs or to explain children’s learning needs to parents in a clear way, etc.”

Even if more proof existed that high teacher scores on reading tests predicted later gains in student achievement, he said, it would be difficult for states to apply a sufficiently rigorous standard that wouldn’t deny licenses to large numbers of teachers.

“Screening out less-knowledgeable candidates could have a positive and powerful effect on teaching,” he said, “or it could just make it harder for schools to hire certified candidates in many communities, so they would likely just hire less-qualified personnel on an ‘emergency’ basis.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)