More Money, More Problems (Solved Correctly): New Study Shows American Kids Do Better on Tests If You Pay for Answers

Much of American students’ poor showing on international math assessments can be explained by an absence of motivation to do well on low-stakes tests rather than a lack of learning, according to a new study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

In an experiment that reproduced math problems from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) test — an influential barometer of international education administered every three years — American students who were offered money for correct answers worked harder and answered more questions right, while Chinese students’ performance was unchanged by the incentive. Among the Americans, male students were more galvanized than girls by the promise of a reward.

The study sheds light on a long-simmering debate over the perennial underperformance of U.S. students on international tests. The United States was assessed 35th in math out of 60 countries on the PISA exam in 2016. Then–Education Secretary John King warned, “We’re losing ground.”

The study was conducted by a team of American and Chinese academics including Uri Gneezy and John List, co-authors of an acclaimed book on behavioral economics.

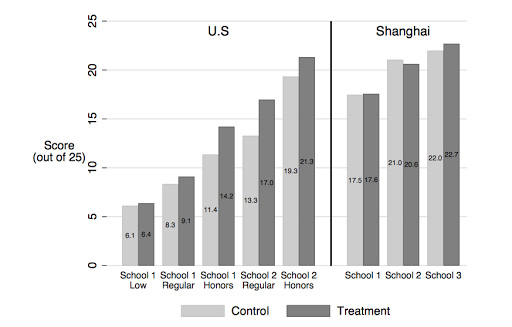

Students from two schools in the U.S. (one a high-performing boarding school, one a large public high school that enrolled both low-performing and average students) and three in Shanghai (one below average in academics, one slightly above average, and one far above average) were given a 25-minute test of 25 math questions that had previously been used on PISA. Just before the test, some of the students were given envelopes filled with 25 one-dollar bills and told that a dollar would be removed for every incorrect or unanswered question.

In the United States, students who were offered the money scored noticeably better than the control group. But the performance of the Chinese students did not improve.

“In response to incentives, performance among Shanghai students does not change while the scores of U.S. students increase substantially,” the authors write. “Under incentives, U.S. students attempt more questions (particularly towards the end of the test) and are more likely to answer those questions correctly.”

If the effects of the experiment carried over to nationwide PISA participants, the research team estimates that American performance would improve by 22 to 24 points. That’s roughly the equivalent of moving from our 36th-place finish (out of 65) on the 2012 exam to a 19th-place result.

A leap of that magnitude might significantly change narratives around our dismal scores compared with international competition. After decades of being shown up by most of the developed world, Americans have grown accustomed to dark prophecies of academic decline.

But those results might be more indicative of apathy than ignorance. Tests like PISA — which have no impact on students’ grades or school accountability measures — aren’t taken as seriously as federally mandated assessments or the SAT.

“The degree to which test results actually reflect differences in ability and learning may be critically overstated if gaps in intrinsic motivation to perform well on the test are not understood in comparisons across students,” the authors write.

The boost in scores was not identical across all American student groups. Those predicted to score around the U.S. average saw the greatest improvement, while those predicted to perform below average gained little advantage from financial incentive.

A gender difference prevailed as well: While scores for American girls increased by about one question out of 25, American boys’ scores improved by 1.76 questions. This imbalance was also present in Shanghai, where boys saw an improvement of 1.13 questions and girls experienced negligible impact.

“Interpreted through the lens of our overall findings, these results suggest that boys in particular lack intrinsic motivation to do well on low-stakes tests,” the authors conclude.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)