‘I Feel Happy to Enter Classes Again’: One Migrant Teen’s Perilous Journey From El Salvador to High School in the U.S.

McAllen, Texas

There are many things that Jerson, 16, doesn’t know. He doesn’t know where he and his dad are going to live, and he doesn’t know where or when he’s going to go to school. He doesn’t know when he’ll see his mom, his two sisters, or his two brothers again.

But, seated at a bus station here on a recent Saturday afternoon after driving more than 1,400 miles from El Salvador with his dad and other migrants, he knows his favorite subject is science. He knows that he wants to be a professional singer, and that he prefers soccer great Lionel Messi over longtime rival Cristiano Ronaldo. He also knows the gist of President Trump’s immigration policy and that it translates into a hard road ahead.

“Yes, he says he does not want more people,” Jerson said of Trump. “But every person fights for what he wants.”

Later this month, Jerson plans to start high school in Arkansas. Because of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1982 decision in Plyler v. Doe, public schools cannot deny any student, regardless of immigration status, access to a public education. If he does enroll, it’ll be the first time in at least eight months that Jerson attends school, and it’ll be a stark departure from how he spent his summer.

In early July, Jerson’s father paid a guide $1,000 for their transport through Guatemala and Mexico to the United States. They had to leave their belongings in Mexico, so when they arrived in the United States, where they were both detained by Border Patrol and briefly separated within the same facility, they were empty-handed.

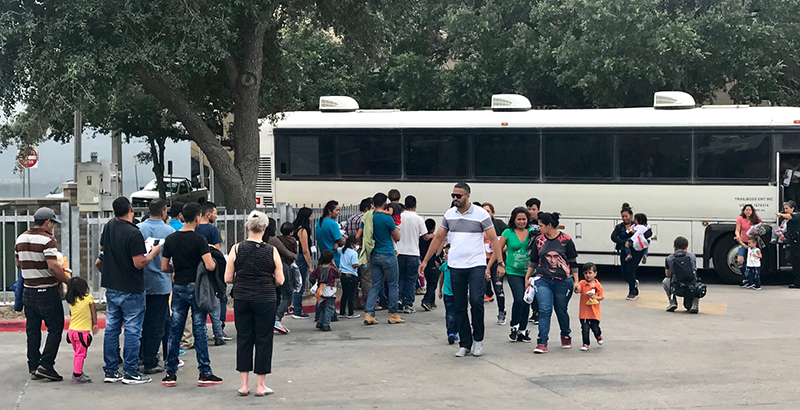

Since a federal judge ended the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” experiment and the government reinstituted its “catch and release” policy, Jerson and his dad were deposited at the bus station. They are among more than 100 Central American migrants who come through the station each day. Nearly 100,000 migrants have come through the station since 2014, according to The New York Times, which recently dubbed it “America’s New Ellis Island.”

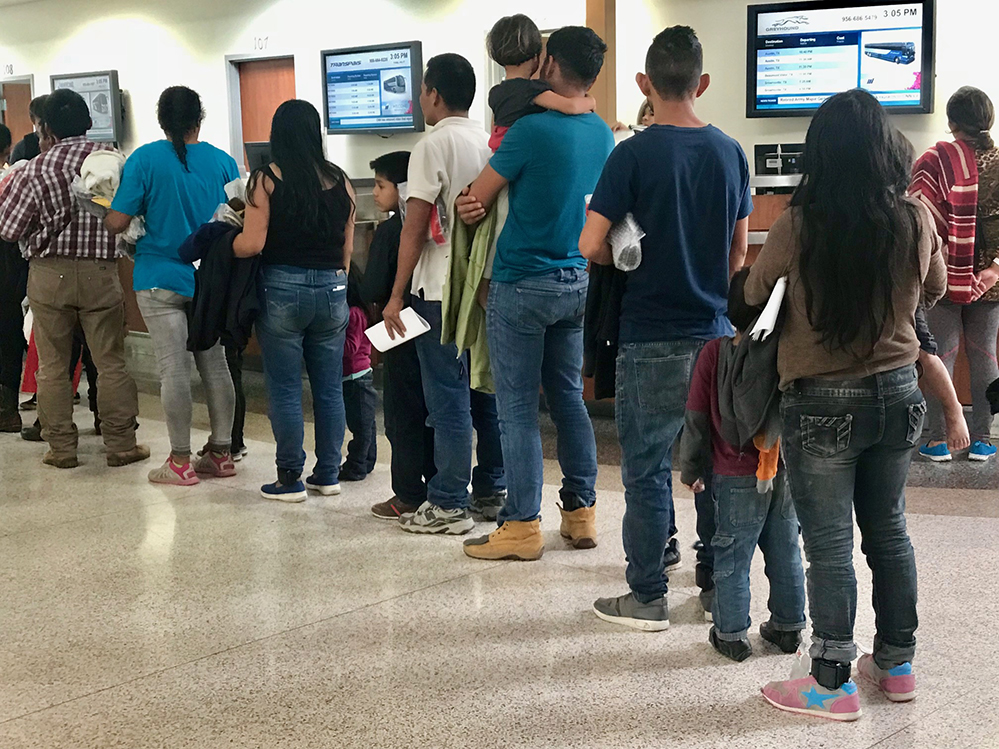

When buses pull up from government detention centers, the migrants — mostly young women and children — get off and meet a volunteer from the local Catholic Charities office. They enter the bus station through a side entrance and form a huddle in the center around the volunteer, who plays the role of quarterback.

In time, the group takes hold of plastic bags bearing the logo of the Department of Homeland Security that hold their remaining possessions, if they have any. They head into the 97° heat, shuffling down the street to the nearby Catholic Charities, where dozens of people sit, stand, and squat in a space intended for far fewer.

On a wall, pieces of paper show the logos of schools that have sent volunteers, who greet migrants at the bus station and help distribute food, toiletries, and clothes: a KIPP school, an IDEA school, a private high school in Indianapolis, and Sidwell Friends in Washington, D.C. Students from Yale are volunteering, as are students from Southern Methodist University.

The migrants then head back to the station as their bus schedules dictate. Jerson and his dad were there to start a three-city, 18-hour journey to culminate in Little Rock, Arkansas, where family friends live. They plan to live there as they wait for an immigration court to rule on whether they can stay in the country, a process that can take years due to backlogged immigration courts.

In Little Rock, the largest school district in Arkansas, Jerson would find some students with similar backgrounds to his own: 13 percent of students there speak Spanish at home. If he ends up elsewhere in Arkansas, he could find greater numbers, especially in the northwestern part of the state. In Rogers Public Schools, the fourth-largest district in the state, 48 percent of students identify as Latino, and one-third of students were English language learners with Limited English Proficiency (LEP) in 2017-18. Springdale School District, the second-largest school district in the state, has added more than 100 Latino staff members and more than 1,000 Latino students over the past five years.

More broadly, among all immigrants, Arkansas had the highest share in the country who were unauthorized in 2012 — 45 percent, according to a Pew Research Center report.

Jerson spoke briefly to a reporter as he waited with his dad for their bus. Wearing jeans and a tan polo shirt with a palm tree pattern, the slim teen said he is cautiously optimistic about his fresh start. He has not attended school since 2017, when he walked an hour each way to attend a tuition-based school in El Salvador that he said was scarce on textbooks.

“On the one hand [I’m] nervous because I do not know how it will be, and [on] the other one I feel happy to enter classes again,” he said.

Gangs had driven him out of El Salvador; the country has one of the highest homicide rates in the world. Now, Jerson is tantalized by the prospect of an opportunity in the United States.

“It makes you want to learn English fast and find a very good job,” he said.

He just doesn’t know how temporary the opportunity may be.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)