EdBuild Report: As Pandemic Threatens School Budgets, Researchers Urge Neighboring Districts to Pool Resources

Updated May 27

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

As the pandemic threatens state education budgets nationwide, a new report by the nonprofit EdBuild urges policymakers to embrace a new method of funding schools that could create equity while shielding districts from steep cuts.

Districts have long relied heavily on property taxes within their own borders to fund schools — a strategy that creates “a strong incentive” for affluent communities to maintain narrow boundaries that exclude their less fortunate neighbors, the education think tank argues. But if school districts pooled local funding at the county or state level and distributed it equally, a majority of America’s K-12 students would have access to better-funded schools without needing to raise taxes, according to the group, which for the past five years has highlighted education inequalities it claims are created by “arbitrary” school district borders.

With states struggling to fill funding gaps created by disparities in local wealth, low-income districts that rely most on state aid face a heightened risk of pandemic-induced funding cuts. This volatility in state education money has long been “an underappreciated flaw” in the way schools are funded, said Rebecca Sibilia, EdBuild’s founder and CEO.

“We are about to understand what a problem that [volatility] is at a level that we have never really understood in modern education history,” she said, adding that state budget cuts could force policymakers to make big changes. “I honestly do not see a way where we can get out of this coming crisis without doing something that substantially changes the way that we’re funding schools.”

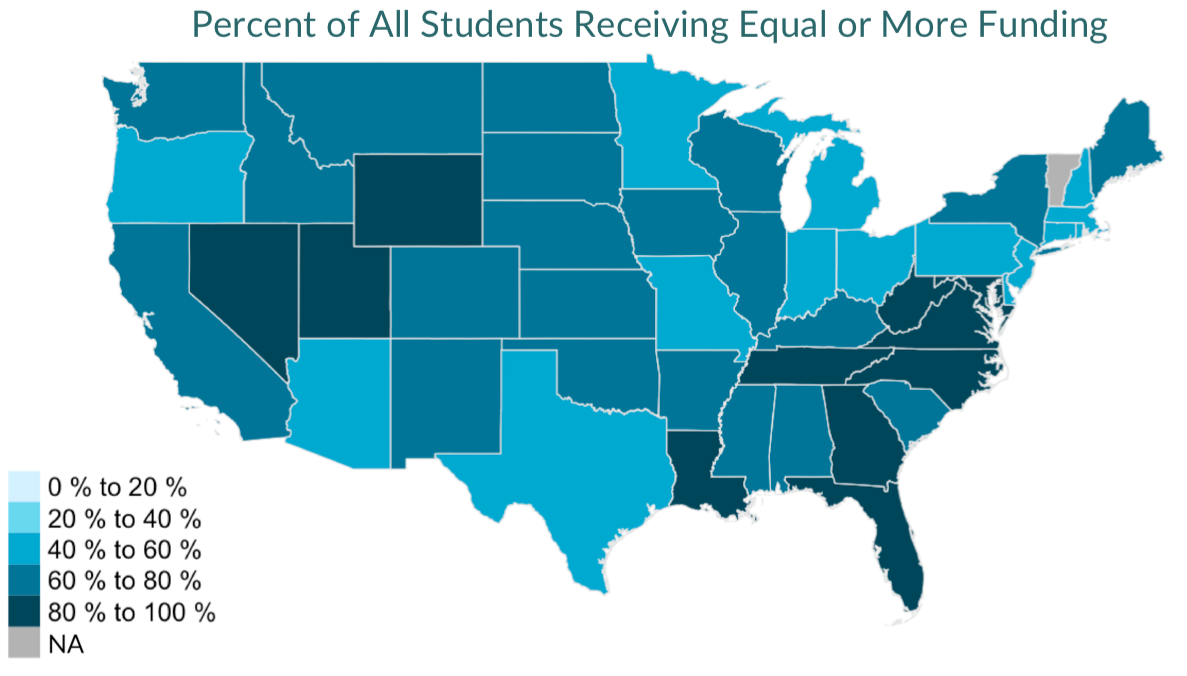

Under the pooled funding strategy, more than 33 million children — roughly two-thirds of America’s K-12 students — would attend public schools with equal or greater funding, the analysis found. In total, the funding strategy would benefit a majority of students in 48 states, where most of the children would see an average per-pupil funding increase of nearly $1,000. Seventy-three percent of children of color and 76 percent of students from low-income households would see equal or greater funding under the strategy, researchers found.

The number of school districts nationwide has dropped precipitously over the past century, yet school districts still outnumber U.S. counties 4 to 1 — with wide variations in student enrollment and funding. Of the nearly 2,000 U.S. counties with more than one school district, the average school funding disparity between the wealthiest and poorest district totals more than $6,000 per student.

To illustrate its findings, EdBuild points to Canadian County in suburban Oklahoma City, home to 10 school districts — six of which serve fewer than 400 students each. The 8,500-student Yukon School District, where the median property value is about $150,000, raises $3,728 per pupil. Neighboring Banner Public Schools, where the median property value hovers above $235,000, raises more than $11,000 for each of its 234 students.

The school district in nearby Calumet fares even better. Because of revenue generated by wind farms, Calumet received more than $20,000 per student during the 2016-17 school year — “money that stays within the borders of a school district that educates just 244 students,” researchers found.

If the better-off districts in Canadian County pooled their local tax revenues, 95 percent of the county’s children would have access to better-funded schools, with the lowest-wealth district receiving an extra 36 percent.

But in Oklahoma and elsewhere, school district consolidation has long been politically contentious, even after a 2018 University of Central Oklahoma study found that the strategy could generate nearly $30 million in savings by reducing administrative costs.

“People really do feel connected to the idea that education is a local thing,” Sibilia said. “What we’re asking folks is to think about localism being just a little bigger than they now know it to be. We’re not asking them to look out for every kid in the country — we’re asking for them to look out for their neighbor.”

But pooling funding wouldn’t require communities to cede local control of their school districts, EdBuild argues. Rather than consolidating multiple school systems into one, communities could create independent tax boundaries that distribute funds equitably between districts while keeping their boundaries — and local decision-making — intact.

Though policymakers nationwide have long failed to address school funding gaps, Sibilia said that she hopes the pandemic ushers in a new urgency to combat education inequities.

“What I hope is that, in our coming season of famine, we may be willing to do what we knew was right all along,” she wrote in the report. “Our motivations no longer need to be the social good because they’ve become the financial reality.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)