Do Parents Actually Want Their Kids in Integrated Schools? New Harvard Survey Reveals Mixed Messages

Correction appended February 4

As schools across the country remain starkly segregated by both race and income, parents expressed widespread support — in theory — for integrating America’s public schools, according to a new report. For many, however, that support appears to stop at their own doorstep.

Across America’s increasingly partisan political divide, parents say they support racial and economic integration in schools and would prefer to send their kids to diverse campuses, according to a Harvard University report released on Wednesday. But when parents actually weigh school choices for their own children, that support often takes a back seat to other issues. School quality and safety are often more important for parents than integration, researchers found.

Parents “care about integration, but they don’t care about it very much,” said report co-author Richard Weissbourd, a senior lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Other factors and their own biases, he said, deter many parents from choosing integrated schools. Weissbourd said parents should walk the walk on integration when selecting schools, noting a body of research that points to positive academic effects.

Integration “is likely to be good for your own children and other people’s children and the country as a whole,” he said. “Parents and schools really need to step up here because it’s unlikely it’s going to happen through the legal system.”

In a computer-based survey of 2,644 American parents from across the country, 85 percent of women and 77 percent of men said they support racially integrated schools. At least half of respondents from all racial groups said they supported integration, though black parents were most in favor, at 68 percent. Support also cut across political parties; 85 percent of Democrats and 76 percent of Republicans affirmed support for racially integrated schools.

But there’s also an interesting election tie-in: Researchers conducted parent surveys before and after President Donald Trump was elected in 2016, and support for racial integration spiked among Democrats after his inauguration, with respondents saying the political climate strengthened their support. Racial overtones in the election likely contributed to the change, Weissbourd said. As leading Democratic candidates promise to address school segregation in their 2020 education platforms, Weissbourd said they should remind parents that combating segregation is a collective responsibility.

The study found that parent support for economic integration was also high, though less profound than it was for racial diversity. Efforts to promote integration also found support, with roughly two-thirds of respondents in favor of district initiatives to achieve racial and socioeconomic diversity — efforts a majority of parents said would benefit both white students and children of color. On average, parents gave the most support to schools that are equally distributed racially and economically.

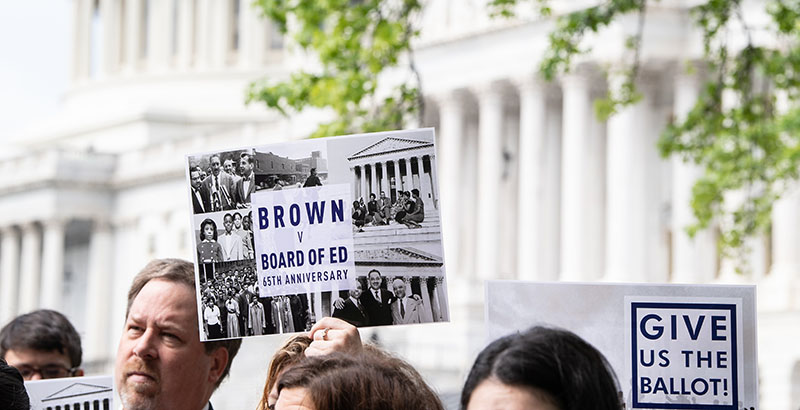

Despite that overwhelming support, however, school segregation persists. For example, about 40 percent of black and Latino children attend schools where students of color comprise between 90 and 100 percent of the student population. More than 65 years after the Supreme Court found school segregation unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education, multiple decisions from the High Court have minimized district obligations to combat segregation.

In the survey, and in telephone interviews and focus groups with parents, researchers found multiple factors that could explain the dichotomy between parents’ stated views and actions. When selecting a school, 81 percent of parents said academic quality is a leading factor, and 70 percent said the same about school safety. Just 10 percent of parents picked racial and economic diversity as a top consideration when actually choosing a school in which to enroll their children.

Their concerns may be warranted, the report notes, since schools with large shares of students of color and those from low-income households tend to have fewer resources and less-experienced teachers. But parents’ information on schools is frequently inadequate, according to the report. Parents often rely on school report cards in both school and residential decisions, though they offer an incomplete picture of school quality, Weissbourd said. Parents also tend to mimic the decisions of those in their social circles, he said, and white advantaged parents often wind up clustered together. Meanwhile, a single episode of violence or bullying at a school can create long-term negative perceptions.

The report urges parents to do more research when picking schools, including campus visits, and to put a greater emphasis on racially and socioeconomically integrated campuses. Those decisions, the report argues, come with stark consequences for communities.

“It might seem that schools are unaffected by individual enrollment decisions,” according to the report, but “the collective impact of those decisions has been a large factor in barricading millions of Americans into marginalization and poverty and deepening the country’s cultural, racial and economic fractures.”

Correction: Based on subsequent information provided by researchers, this story has been updated to reflect that after Donald Trump’s inauguration in 2016, support for racial integration in schools spiked among Democrats.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)