Disadvantaged Kids Don’t Have Equal Access to Great Teachers. Research Suggests That Hurts Their Learning

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

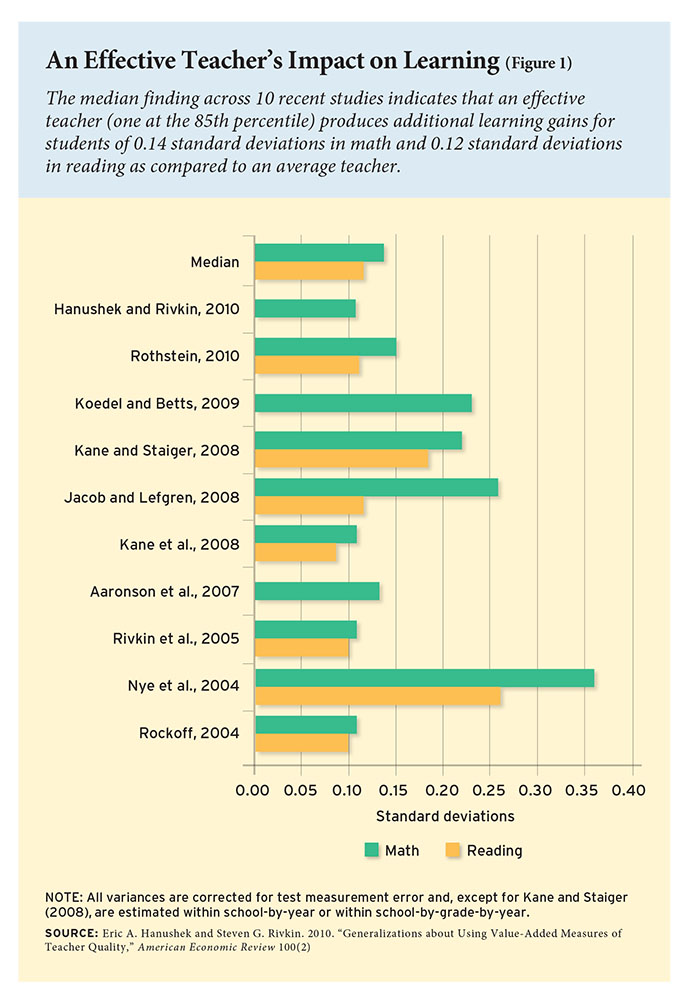

Differences in the quality of elementary and middle school teachers can explain much of why disadvantaged students perform worse in math than their whiter, more affluent schoolmates, according to a working paper circulated by the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER). The authors caution, however, that our understanding of teachers’ effects on students depends on how we measure teacher quality.

The study, conducted by CALDER director and University of Washington professor Dan Goldhaber, synthesizes two separate research topics: the influence of teacher quality on student achievement, and the inequities in access to excellent teachers that persist along racial and class lines.

Roughly one-sixth of white students’ edge over their minority classmates in eighth-grade math tests is due to simply having better teachers, the authors conclude, and over one-fifth of the gap between poor and non-poor students is also traceable to teacher quality.

Voluminous research published over several decades has shown that low-income and minority students have less access to high-quality teachers, regardless of whether “quality” is defined by traditional qualifications — years of experience, possession of an advanced degree, performance on teacher certification exams — or by the somewhat controversial measure of “value added,” which tracks the impact of instructors on student test scores.

Goldhaber has published multiple studies and briefs trying to get at the importance of teachers’ performance in the classroom and how that performance ought to be calculated. He says that the development of teacher quality gaps isn’t particularly surprising, since states and school boards tend to view teacher job assignments as fungible — even if it’s actually much harder to teach in a high-poverty district or school than a more affluent one.

“You’d expect that there would be teacher quality gaps because there’s very little differentiation between teacher salaries within a school system,” he told The 74 in an interview. “Teachers don’t have quality measures stamped on their forehead, but you could imagine that the better teachers would have some advantages in that kind of labor market, and would get the choice teacher assignments.”

So experienced, well-credentialed teachers — and those who boast high value-added scores — cluster in more desirable job placements; perversely, those are often in schools with greater numbers of white, middle-class, and high-performing students, who are already succeeding by most academic standards. The question is: How does this inequitable distribution of teacher skill affect how students learn?

To find an answer, Goldhaber and his co-authors examined student-level data from the state of Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction between the 2006–07 and 2015–16 school years. They linked students to their classroom instructors between the fourth and eighth grades, and then examined their performance on eighth-grade math exams. To introduce a new area of inquiry, they also looked at which students later took advanced math classes (precalculus and above) in high school.

Ultimately, they find the importance of teacher quality to be significant. If black, Hispanic, and Native American students and white students had equivalent teachers in grades four through eight, gaps in eighth-grade math performance would shrink by 16 percent; gaps between students based on eligibility for free and reduced-price lunch (a common measure of student poverty) would be 21 percent smaller.

Even more striking, a full 33 percent of the gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students in advanced high school math courses can be attributed to teacher assignment.

But a lot depends on how teacher value added is determined, and specifically whether measures of value added focus on individual student performance or account for classroom characteristics. Some existing research has found — and the CALDER study reaffirms — that controlling for “peer effects” (e.g., whether a student’s classmates are top performers or falling behind, well-behaved or disruptive) reduces observed gaps in teacher quality. Even very skilled instructors may look worse, the thinking goes, when placed into classrooms where many students are struggling to learn.

Echoing other studies, the authors find that nothing is more predictive of later academic performance than earlier academic performance. Somewhere between 63 percent and 75 percent of the gaps between advantaged and disadvantaged students on eighth-grade math is associated with their gaps on third-grade math.

“Policy makers wishing to alleviate later achievement gaps either need to intervene earlier in a student’s academic career or be far more aggressive after the third grade to address academic deficiencies,” they write.

To fully explore the insights provided by different measures of teacher quality, Goldhaber told The 74 that he and his co-authors plan to eventually split the existing working paper into at least two: one that will examine the link between teacher value added and student performance, and one looking at different models of value added.

Regardless, he says, unequal access to educational resources will continue to be a reality for poor and minority students as long as the toughest teaching jobs are treated the same as cushier assignments.

“You can’t overstate how tough a problem this is. If you’re talking about a single salary schedule, which I think treats a teaching job as pretty generic, I think you can expect this problem to arise.”

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)