Charters Employ More Diverse Teachers Than Traditional Public Schools. Is It Giving Them a Leg Up With Minority Students?

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

Over the past few years, education researchers have coalesced around a striking, if somewhat unpalatable, observation: Kids learn more from teachers of their own race.

A decade of studies from Tennessee, Florida and North Carolina has shown that K-12 students perform better academically if they’ve been assigned to a same-race teacher. Though the effects have been observed in white students, they are especially pronounced in their black classmates, who are less likely to drop out of school and more likely to complete a college entrance exam if they are exposed to even one black instructor in elementary school. Black educators also issue fewer suspensions to black students, and more referrals to gifted education classes, than white educators.

A study released today from the conservative Fordham Institute adds a notable new facet to the existing research, finding that black students are much more likely to encounter a same-race teacher in a charter school than a traditional public school. And the study’s author, American University professor Seth Gershenson, says that the greater likelihood of racial matching might help explain charters’ success with minority students.

The study examined all North Carolina public school students between grades 3 and 5, in both district and charter schools, between the 2006-07 and 2012-13 school years. In total, it gathered 1.8 million observations of students, including their race and student year, their teacher’s race, and their score on end-of-year assessments in both math and English.

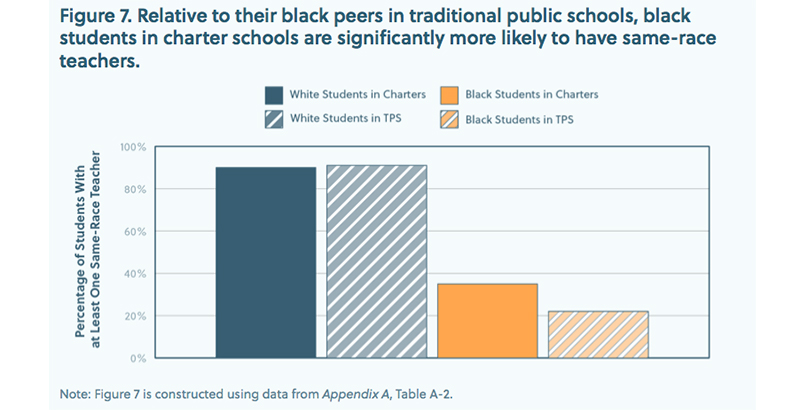

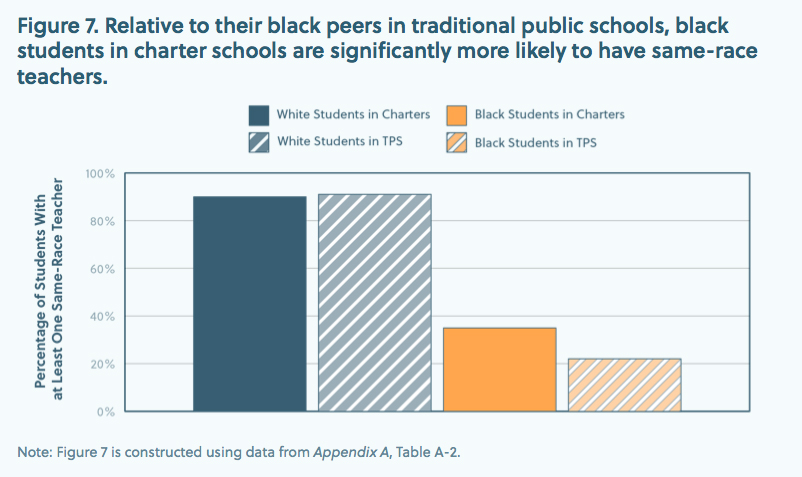

Those data indicate that, while charter schools enroll a similar percentage of black students as traditional public schools, they employ more black teachers — about 14 percent of their teaching workforce, as opposed to roughly 10 percent of those in district schools. Partly as a result of the greater abundance of black faculty, black students are 50 percent more likely to be assigned to a black teacher in a charter than they are at a traditional public school.

As in previous studies, students in both charters and district schools received a measurable academic benefit from being assigned to a same-race teacher; on average, the effect size was about the equivalent of eliminating 10 teacher absences over the course of one school year. But the boost in test scores for racially matched students was about twice as large for charter students as for traditional public school students.

Though the race-matching impact was nearly doubled for charter students, the difference was not deemed statistically significant, in part because the number of charter students featured in the study was relatively low (just 30,000 observations were made over seven academic years, versus more than 1 million such observations for district schools). But in an interview with The 74, Gershenson said that he believed the distinction would have been preserved over a larger sample size.

“Twice as big of an effect is still twice as big of an effect, and that’s a big deal,” he said. “If we had as many charter schools as we did traditional public schools, I suspect that we would have more precisely estimated that difference.”

National research has indicated that teacher demographics at charter schools tend to be more heterogeneous than those in traditional public schools. A longitudinal report released earlier this year by the National Center for Education Statistics found that 29 percent of charter teachers were black, Hispanic or Asian, compared with 19 percent of those in district schools.

Gershenson said that the higher rates of teacher diversity are a largely unremarked-on feature of charter schools, and one that might go a long way to explaining their relative success with students of color. Though practices differ by jurisdiction, charters are generally allowed to hire employees without conventional teacher certifications; the requirement to attain a teaching degree, which can come at substantial cost, has been cited as a hurdle to achieving a more representative teacher workforce.

“This is an important finding in its own,” he said. “And I don’t think the research world or the charter policy world pay enough attention to this point, precisely because we don’t have a great idea of what makes effective charters effective. You can view racial representation among teachers as a measure of teacher quality, and that’s a dimension of teacher quality that charters have an advantage in.”

Disclosure: Kevin Mahnken was an editorial associate at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute from 2014 to 2016.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)