Brookings: New Revelations About Teacher Vacancies — and Which Students Go to Those Schools

Schools afflicted with hard-to-fill teacher vacancies are also more likely to enroll minority students, according to a new report from the Brookings Institution. Both minority students and teachers are more likely to be clustered in schools with one or more such vacancies, the report finds.

Written by Brookings senior fellow Michael Hansen, the report addresses recent attempts by states to effectively kill two birds with one stone by hiring black and Hispanic teachers to counteract persistent staff shortages at schools that predominantly teach black and Hispanic students.

On the one hand, teacher vacancies in hard-to-staff disciplines like STEM and special education can often drag on long into the school year, resulting in abrupt staffing changes and an unhealthy reliance on substitutes. Studies have shown that elevated teacher turnover, and the vacancies that result from it, are harmful to student achievement.

At the same time, America’s rapid demographic transformation in recent decades has produced schools where overwhelming majorities of white teachers preside over classrooms with steadily growing numbers of non-white students. That’s worrisome to many researchers and student advocates, who point to an ample body of evidence showing that minority students score higher on standardized tests and drop out at lower rates when exposed to at least one teacher of their own ethnicity.

Schools serving large minority populations tend to suffer the highest rates of teacher turnover and shortage. Noting the linkage between the two problems, several states have announced initiatives to curb shortages paired with financial incentives to increase teacher diversity. The result, ideally, would be fewer shortages and more minority representation in the teacher workforce at the same time.

That approach is flawed, according to Hansen, for a simple reason: Schools with the greatest need for more non-white staff are less likely to experience vacancies, and those that struggle to fill jobs already employ proportionately more teachers of color.

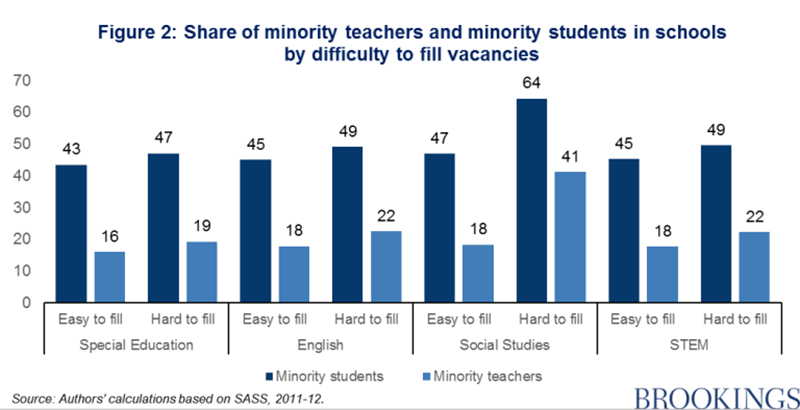

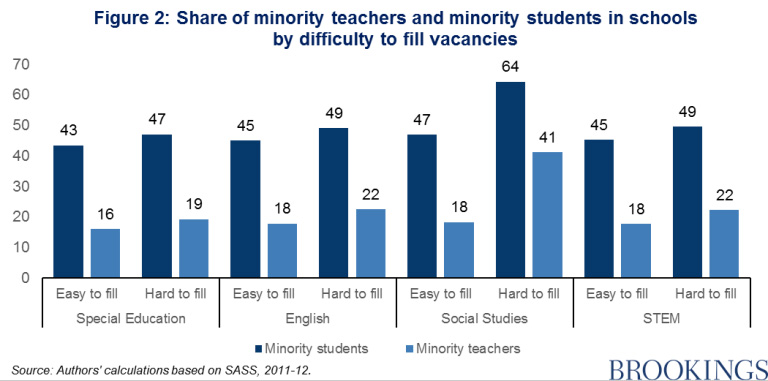

Citing data from the Schools and Staffing Survey, a regular poll conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics, Hansen shows that minorities represent 41 percent of the student population in schools with no social studies vacancies, but 48 percent of the population in schools that do have vacancies in that subject. In schools with vacancies in STEM, minority students make up 46 percent of the population, noticeably higher than the 41 percent of students at schools with no STEM vacancies.

Further, minority students are even more concentrated in schools with hard-to-fill vacancies. In other words, the more difficult it is fill a job opening at a given school, the more likely that school is to educate high percentages of minority students. For instance, minority students account for 47 percent of the student population in schools with easy-to-fill vacancies in social studies, but that number jumps to an incredible 64 percent in schools that struggle to fill those roles.

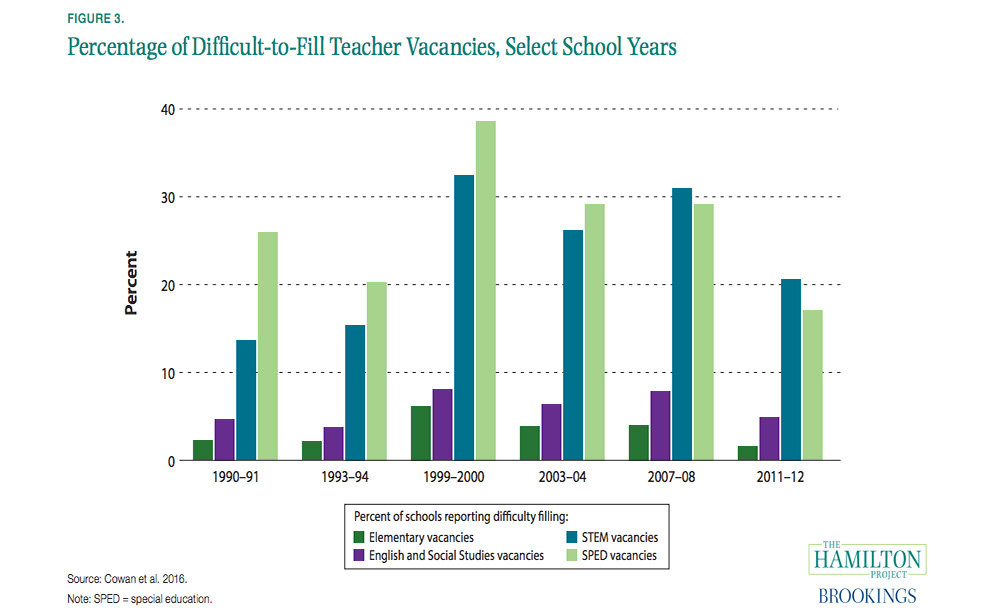

It should be mentioned that, compared to science, math, and special education, subjects like English and social studies are relatively easy to staff. In a report for the Hamilton Project, Stanford professor Tom Dee found that the percentage of schools reporting vacancies in social studies has always remained much lower than those reporting vacancies in other subjects.

A school that struggles to hire social studies teachers, therefore, is experiencing very acute staffing troubles. And those schools tend to enroll many more minority students.

But the catch is that such schools also employ more minority teachers. While the percentage of minority students jumps by a startling 17 points between schools with easy-to-fill and hard-to-fill social studies vacancies, the percentage of minority teachers leaps by 23 points, from 18 percent to 41 percent. Similar increases, though not of the same magnitude, are observed when vacancies get harder to fill in English, STEM, and special education.

The upshot, he notes, is that although schools with vacancies (and especially vacancies that they struggle to fill) enroll more minority students, the problem of demographic mismatch isn’t necessarily worse at those schools, because they also employ more minority teachers already.

“Schools facing shortages — at least from this national perspective — do not show any systematic pattern of minority underrepresentation,” Hansen concludes. “Further, schools with many hard-to-fill vacancies had some of the highest teacher minority shares in the analysis. Hiring more minority teachers specifically to these schools would simply concentrate them where they already teach in high numbers.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)