Study: Kids Who Struggle With Executive Function Vastly More Likely to Experience Academic Difficulties

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture‘ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

Kindergartners who experience deficits in executive function — a set of cognitive skills that allow people to plan, solve problems, and control impulses — are much more likely to face academic difficulties in elementary school, according to a new working paper that was presented to the American Educational Research Association’s annual meeting Friday. In math alone, their odds of struggling by third grade are increased fivefold, authors find.

The study, conducted by Pennsylvania State University professors Paul Morgan and Marianne Hillemeier and University of California Professor, Irvine, professor George Farkas, is the latest in a growing body of research exploring the connection between executive function and student achievement. Prior experiments have suggested a link between the two but largely demurred on whether particular skills could be honed to improve academic performance.

Morgan, Hillemeier, and Farkas focus particularly on the EF skills of working memory, the ability to retain information over time; cognitive flexibility, the ability to shift between different facets of a problem and integrate new information to solve it; and inhibitory control, the ability to look past distraction and stay on task.

Children often stumble in developing all three if they have developmental or learning disorders or have suffered brain injuries or other trauma. In the classroom, the absence of these abilities sometimes manifests in disruptive behavior or an unwillingness to learn. Kids experiencing EF deficits can be overwhelmed by relatively straightforward tasks and have a hard time dealing with frustration.

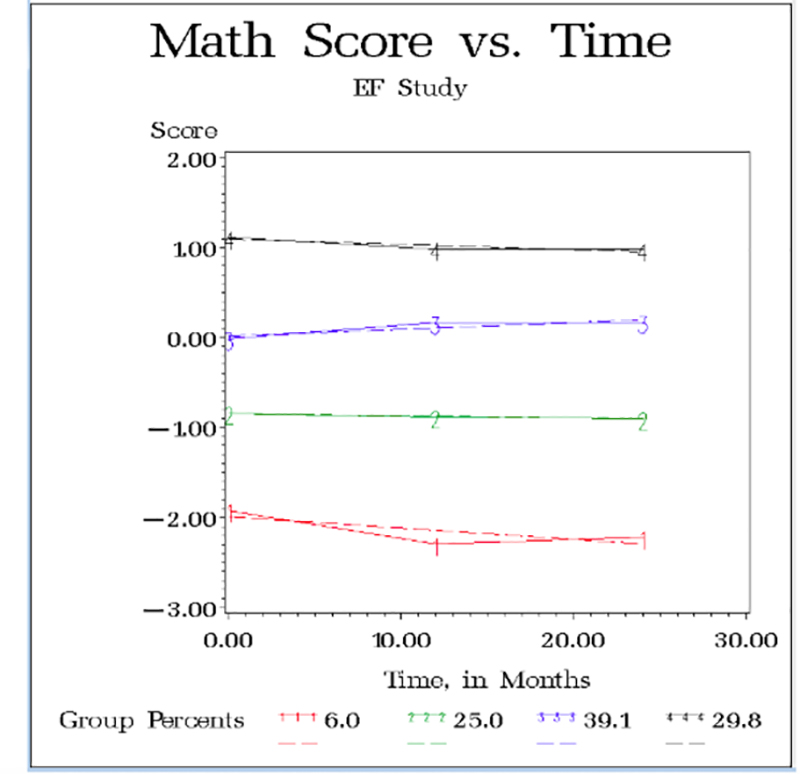

The authors studied a nationally representative sample of over 8,000 children participating in the Department of Education’s Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey–Kindergarten Cohort of 2011. The survey assessed students’ proficiency in math, reading, and science, as well as their development of the three EF skills, in both spring and fall of the years between kindergarten and third grade.

Children were asked to remember and repeat a sequence of number combinations to test their working memory. To demonstrate cognitive function, they sorted picture cards by color, shape, and border. And to gauge inhibitory control, teachers instructed children to complete a task and then evaluated whether they could be distracted from completing it.

Participants who showed signs of deficits in EF skills were much more likely to experience repeated academic difficulties in first, second, or third grade. After controlling for the students’ race, gender, socioeconomic status, and English language status, the authors found that problems with any of the three EF skills were predictive of low math achievement.

Working memory was revealed to be a particularly notable risk factor. Children with deficits in their working memory were at five times greater risk for low achievement in math, 2.8 times greater risk in reading, and 2.3 times greater risk in science. The odds of experiencing repeated reading difficulties were roughly two times greater for children with a lack of inhibitory control than for those without.

The research team notes that its findings are not causal and that experimental studies are necessary to substantiate the connection between executive function and school performance. Other researchers, like University of Michigan professor Robin Jacob and the American Institutes for Research’s Julia Parkinson, have expressed skepticism about interventions that target executive function deficits to solve math or reading deficits. As the development of “brain-training” games and software has grown into a billion-dollar industry, a lively debate has been waged over whether it is truly possible to enhance brain function for children or adults.

The authors suggest that the potential exists to design treatments combining cognitive and academic development — particularly if they focus on building working memory.

“Our analyses suggest that experimentally evaluated interventions designed to remediate working memory deficits as well as academic skills deficits during kindergarten might be expected to be more effective in reducing children’s risk for repeated academic difficulties than efforts designed only to remediate academic skills deficits, including across multiple academic domains,” they write.

Go Deeper: See all our coverage of eye-opening education research and analysis in our ‘Big Picture’ Series — and get the latest posts delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for The 74 Newsletter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)