Ye, Kyrie Irving Show Why Schools Need to Teach Black History of the Holocaust

Trisko Darden: Forging connections between anti-Black violence, Jewish history shows students how events that affect one community affect us all

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

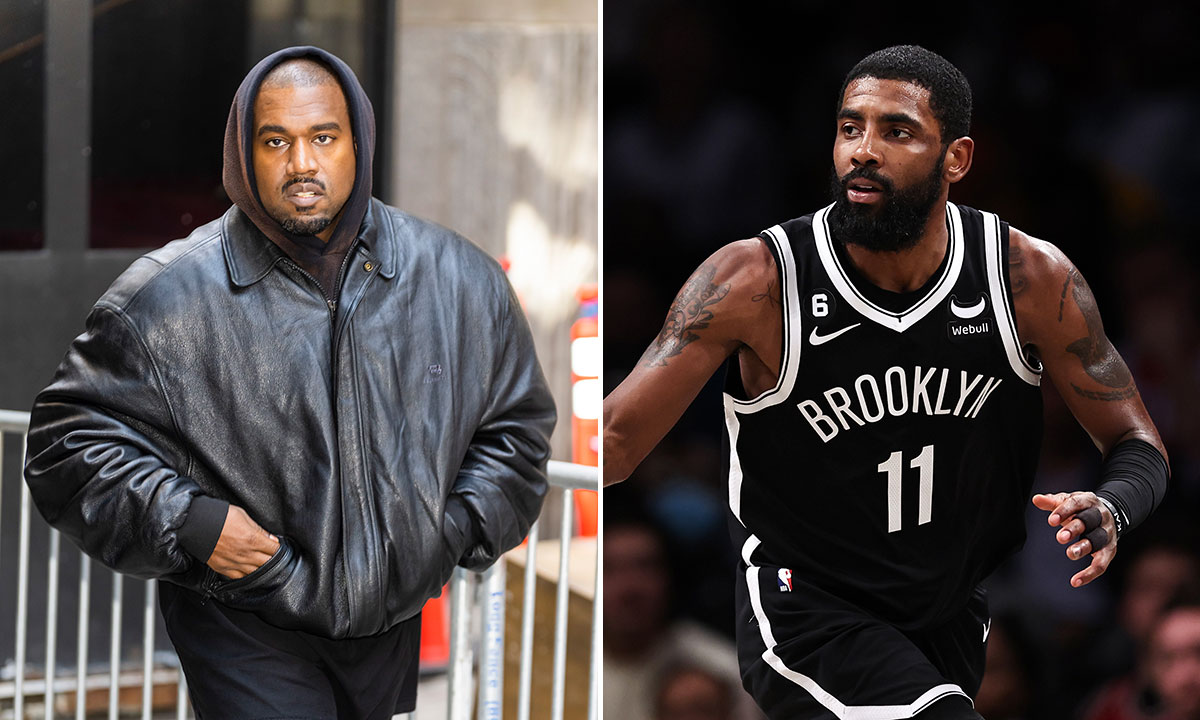

The past year has seen several prominent Black celebrities making anti-semitic remarks. Rapper Ye (formerly Kanye West) proclaimed in an interview with Alex Jones, “I like Hitler … I love Jewish people, but I also love Nazis.” Brooklyn Nets star point guard Kyrie Irving promoted on social media a film that included elements of Holocaust denial. Whoopi Goldberg stated on television that race was not a factor in the Holocaust.

In the face of centuries of anti-Black violence in America, it has become easy to dismiss the Holocaust as Europeans killing other Europeans, as “white-on-white” violence. This notion completely misses the Black history of the Holocaust, the details of which are lost because educators rarely teach it.

The Holocaust was the systematic murder of 6 million European Jews, and the centrality of Jewish identity to the perpetration of the Holocaust must not be forgotten. But thousands of other individuals from a diverse array of communities — including persons with disabilities, LGBTQ people and members of other religious minorities — were also targeted by Nazi ideology. This included Black Germans.

While anti-semitic remarks from celebrities draw headlines and outrage, they are ultimately a symptom of a deeper problem: the failure of educators to teach about the Holocaust in ways that relate it to other marginalized communities’ experiences.

I teach courses on political violence at Virginia Commonwealth University, a minority-serving institution in Richmond — the former capital of the Confederacy. The students in my classroom have the same blind spot about Holocaust history as those celebrities. Yet, I’ve connected with my students in profound ways by studying the Holocaust and allowing them to forge their own personal connections to the victims and survivors of Hitler’s attempt to wipe out Jews and other minorities.

Sadly, the anti-semitism that motivated Nazi ideology has been mainstreamed in American culture and political discourse. Still, when tasked with rooting it out, students are readily able to identify anti-semitism. One student highlighted an anti-semitic flyer circulated by a politician running for county office. One drew a connection between South Park’s Islamophobia and anti-semitism. Another supplied far too many quotes from Ice Cube. Young people from diverse backgrounds are able to recognize anti-semitism when they see it, but they struggle to understand where it comes from and why it affects them.

That’s why I teach the Holocaust through an intersectional lens that reveals the relevance of religious, racial, gender and sexual identities. While the deep roots of Nazi ideology are found in European anti-semitism, the forerunners of Nazi policy can be found in the colonization of Africa. Germany’s colonial genocides that began in 1904 in contemporary Namibia were acknowledged by the German government only in 2021. The annihilation of the Herero and Nama peoples by German forces, through tactics such as forced starvation, deportation to concentration camps and medical experimentation, provided a blueprint for the Holocaust. But that isn’t the only connection.

Nazi racial policy was built around the concept of eugenics, which held that mental illness, poverty and criminality were biological traits passed down from one generation to another. Popular in the United States as well as Western Europe, eugenicists sought to control who could have children as a way of addressing social problems. Virginia enacted eugenic laws in 1924, the same year it banned interracial marriage, and allowed state institutions to sterilize individuals to prevent the conception of so-called genetically inferior children. Virginia’s law became a model for the country after it was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in Buck v. Bell in 1927. Twenty-two percent of the more than 7,000 individuals sterilized in Virginia alone were African Americans, and two-thirds were women.

Similarly, Nazi eugenics focused on the elimination of Afro-Germans — Germans of African descent. Hitler wrote about Afro-Germans in Mein Kampf, arguing that they defiled Aryans’ racial purity. Black and mixed-race people in Nazi Germany were subject to discrimination and violence similar to that inflicted on Jews. Ye may like Hitler, but if he and his family had lived in Nazi Germany, they would have been socially and economically marginalized and potentially subjected to forced sterilization. The history of Nazi-era discrimination against Afro-Germans continues to affect Black people living in Germany today, with many reporting that no area of their life is unaffected by racism.

Teaching Black history alongside Jewish and other histories of the Holocaust helps connect it with students’ own experiences with discrimination, violence and hate. It can also help educators better understand their students. As one of my students wrote while reflecting on an image of Germans mocking their Jewish neighbors as they were rounded up and deported to a Nazi concentration camp, “I know the fear of deportation, of being taken away from your home and all you know, and just imagining people I’ve known all my life enjoying me losing everything, I can’t even explain how horrible that feels.” The experiences of the Holocaust still have meaning for marginalized students today.

By forging connections between Black history and Jewish history, between the exploitation and murder of colonized peoples and the Holocaust, between marginalized communities, educators can help students of all backgrounds make important emotional and intellectual connections between the Holocaust and the bigotry and discrimination experienced by marginalized communities. Teaching the Black history of the Holocaust demonstrates to students how events that seemingly affect only one community ultimately affect us all.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)