Without a Green Light From Texas State Officials, Superintendents Move Ahead to Safely Open Schools for Kids Who Need Them Most

Texas education officials haven’t given them the green light, but two San Antonio superintendents are moving ahead with plans to safely open schools on their own timeline starting with the neediest students.

With in-person reopening strategies based on local COVID-19 data and student need, the superintendents say that after discussions with state officials, they believe the Texas Education Agency will back down from its original mandate that schools reopen to all students after the first four to eight weeks online.

“It’s not flipping a switch; it’s slowly turning a valve,” Northside Independent School District Superintendent Brian Woods said of his district’s plan to refill classes.

Woods and San Antonio Independent School District Superintendent Pedro Martinez plan to bring back small groups of students in phases, carefully scaling up classrooms, and starting with those with the greatest need, in accordance with COVID-19 metrics in the community. They want to follow this course for as long as needed.

The Texas Education Agency has so far insisted on a dramatically different plan: After weeks of online-only instruction, schools would fully reopen, and any student who wanted to would be allowed to return.

While Woods remains poised to fight for control of his district, Martinez is confident that Texas Education Commissioner Mike Morath will approve the plans.

“All of my interactions with the commissioner have been not only positive, but he’s very reasonable,” Martinez said. SAISD’s reopening plan is currently featured on the Texas Education Agency website as an example of a strong reopening strategy during the eight-week on-ramp. Martinez said he believes the state will allow them to continue beyond October to reopen all schools. “If it takes us all the way to November, it takes us to November,” he said.

Because the district has an explicit goal of having students in their ideal learning environments as soon as safely possible, Martinez believes the state will trust their judgement, he said. “Maybe I’m overly optimistic that when we show our plan and how methodical it is, I’m confident we’re going to be successful getting any flexibility we need.”

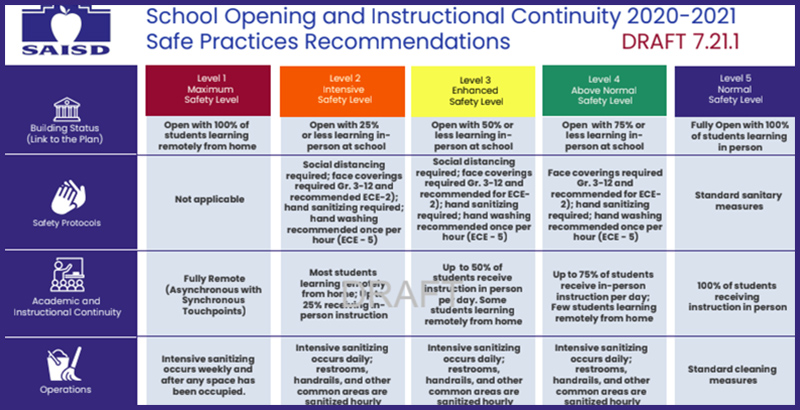

The district’s plan dictates how many students each campus should bring back based on the community positivity rate, the case load doubling time, and the two-week trajectory of local cases (increasing, decreasing or flat). When all indicators permit, the district will move to the next phase of reopening.

Each phase increases the number of students in buildings. Even that increase, however, Martinez said, will not happen all at once. The more slowly they can bring students in, he said, the more likely teachers and students will be able to learn and adopt safety protocols.

The notion of an arbitrary deadline to reopen schools defied public health expectations, Woods said: “The virus doesn’t care about what week it is.”

Woods remains less optimistic about the state’s willingness to trust independent school districts. He wants to see the promise of the new waiver in writing. “They have not backed down,” he said, referring to state officials.

The Texas Education Agency did not respond to a request for comment on the likelihood of a waiver.

Woods has publicly threatened to pursue legal action against the state if it withheld funding from districts that did not comply with sweeping reopening plans. If, at the end of eight weeks, no new waiver has been granted to allow districts to stick to their phased reopening plans, Woods said he will still prioritize his own plan to bring back homeless students, special needs students and those who are in unsafe environments first.

Preemptively taking the Texas Education Agency to court or simply going ahead with the district plan and “daring them not to fund us,” Woods said, “may be two sides of the same coin.”

Educators and public health advocates say timelines like the one proposed by the state required schools to plan for reopening based on too many unknowns: How many parents would choose “in-person”? What if there were a sudden spike in local cases? What if classrooms become too full for adequate social distancing?

In Woods’s district, the largest in San Antonio, he has seen wide campus-by-campus variation in who wants to come back to school in person. Overall, only 35 percent of students want to come back in person for the first nine-week grading period, with 15 percent undeclared and the rest opting for virtual learning until at least October. That’s manageable, Woods explained, but at some schools the preference for in-person was as high as 70 percent.

“Schools aren’t designed for social distancing,” Woods said. “We have to have some control over who’s in the building.”

On Aug. 18, the district announced a four-phase plan to keep all campuses moving at the same pace, in accordance with COVID-19 risk in the city.

Districts will submit these reopening plans with a request for a waiver to allow them to use academic data, teacher feedback and parent preference to bring back students incrementally.

San Antonio Independent School District has also worked closely with the Metropolitan Health District to devise a color-coded reopening plan to bring back small percentages of students as community spread of COVID-19 slows in the city. Superintendent Martinez is confident that their plan will win state approval.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)