With Welding Tools and a Time Clock, How One New Mexico Teacher Is Giving HS Students a Leg Up on the Future

Engineering the Future, Valley High School’s magnet program, has 6 career tracks that are a model for the district — and maybe for the entire state

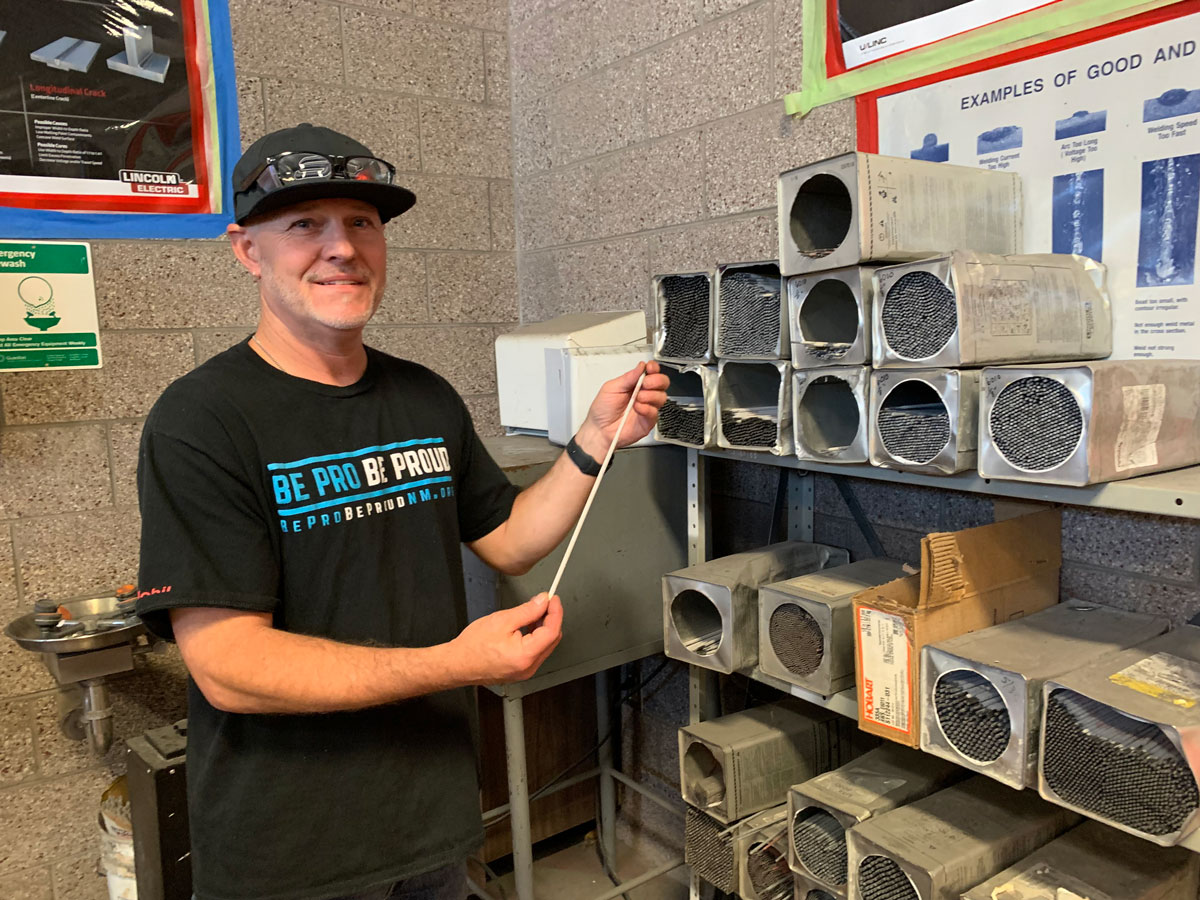

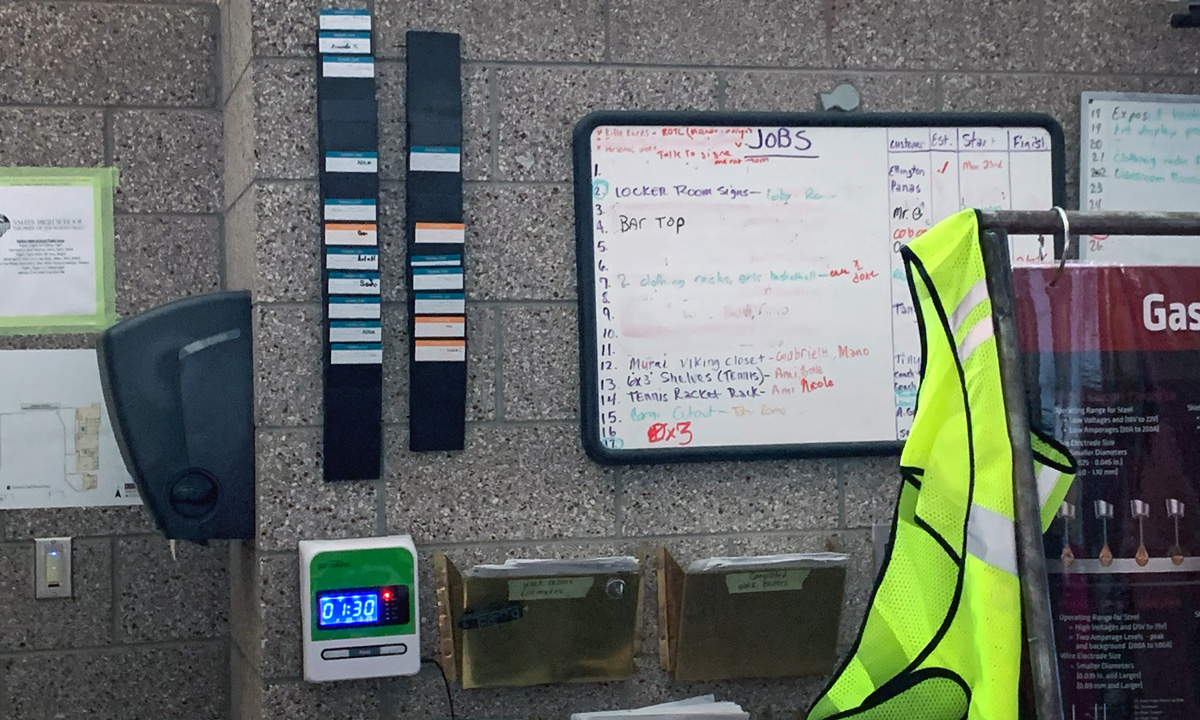

By Beth Hawkins | July 30, 2025The magic moment might have been when welding teacher Shawn Coffey bought an old-fashioned time clock and installed it next to the door of his classroom at Albuquerque’s Valley High School. The idea was simple: He wanted his students to develop good workplace habits, like punching in on time.

Located in an engineering-themed magnet school near the Rio Grande, Coffey’s workrooms are packed to the literal rafters with pieces of metal displaying good welds and bad, crude joinery and more sophisticated bezels and, on a ledge ringing the front room, boxes that students make to prove they know how to use the spark-spitting tools — safely.

Those boxes represent a concrete step toward real careers. In an arrangement unusual for a U.S. high school, Valley’s partnerships with local trade unions give students a head start on apprenticeships — the years-long paid training paths that are the first building block of a solid career.

Last year, leaders of Sheet Metal Workers Local 49 had paid Coffey’s shop a visit. The clock immediately caught their attention: The two years of “shop hours” documented on the students’ time cards would entitle some of them to leapfrog the lowest rung on the welding career ladder.

High schoolers aren’t yet eligible to call themselves apprentices, something that changes the day after graduation. But thanks to the time clock, Coffey’s graduates not only got to wear a sash proclaiming their new trade union home over their graduation gowns; on the strength of the hours and training recorded on their cards, many received 18 months of credit toward completing a four-year apprenticeship and, for some, a starting wage of $24 an hour, rather than the usual $18.50 entry-level pay.

The $15 an hour Albuquerque Public Schools pays Valley’s student-interns to tackle projects throughout the district also counted as work experience in the union’s eye, adding several dollars an hour more.

Welding is one of six career preparation pathways that make up Valley’s magnet program, Engineering the Future. The others are architecture, computer science, carpentry, JROTC and engineering. Last spring, three graduates went directly into carpentry apprenticeships.

Nationally, the number of partnerships between trade unions and schools is ticking up — particularly in states where officials push for better career and technical education. But if students get any credit for their high school experience, it’s usually deemed a pre-apprenticeship. An estimated 5% or fewer get paid internships.

For people looking to enter the trades, though, apprenticeships are the gold standard. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, in 2024 just 10,000 of the of the more than 13 million students ages 16 to 18 began apprenticeships nationally, including 18-year-olds who started after graduating high school. Average starting pay for those who complete any four-year apprenticeship training track is $80,000 a year.

Valley’s Engineering the Future program predates the current college- and career-readiness push. It launched in the 2018-19 academic year as a magnet school, enrolling students from anywhere in the district. More than a fourth of Valley students overall are learning English, while an eye-popping 36% receive special education services.

Students who spend at least three years in one of the training programs, participate in an outside STEM competition or school showcase and complete a self-reflection earn an Engineering the Future “distinction stole” — a sash embroidered with emblems signifying their accomplishments, and in some instances their new trade — to wear at graduation.

Altogether, 436 of Valley’s 949 students participate in a career pathway, with some enrolled in more than one program. In 2025, 45 seniors earned Engineering the Future stoles, which were bestowed several days before graduation at a separate ceremony celebrating students’ new jobs and union affiliations.

As chocolate-meets-peanut butter moments go, Coffey’s decision to put up a punch clock was spectacularly well timed. New Mexico has long lagged in students’ academic and post-secondary outcomes, ranking last in the nation for nine consecutive years in the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Kids Count Data Book report.

In 2018, a district court found the state violated students’ right to a sufficient education, as guaranteed in New Mexico’s constitution. Among other shortcomings, the judge overseeing the case said, students have a right to be college- and career-ready, and she ordered state education officials to ensure that historically underserved children are set up for success after high school.

State officials and attorneys for the families who brought the lawsuit were still going back and forth when COVID-19 forced schools to close for in-person classes. Attendance rates have traditionally lagged in New Mexico, but coming out of the pandemic they were in free fall.

Between 2019 and 2023, the number of students missing 10% or more of school days shot up 119% — the largest increase in the country — to 40%. In the 2021-22 school year, 43% of Albuquerque Public Schools students were chronically absent.

In January 2022, the district released a five-year plan to address basic academic outcomes, student habits and mindsets, and college- and career-readiness. One goal is to increase the percentage of high school graduates who earn a bilingual diploma, credit in college prep courses or an industry certification from 40% in 2023 to 50% in 2028.

A year ago, a member of the team that created the plan, Gabriella Duran Blakey, was tapped to lead the district. In a speech outlining her agenda, Blakey lauded Coffey for propelling graduates into careers.

When school starts Aug. 7, two high schools will launch “freshman academies” — year-long programs where ninth graders are introduced to different career pathways in nine-week cycles. The goal is for every student to choose a career-focused academy during sophomore year. Eventually, district leaders want each of the system’s 13 comprehensive high schools to have a college or career focus.

It’s a huge undertaking, according to Mia Howard, a leader of the New Schools Venture Fund’s innovative public schools team. The district will need to ensure that the new programs align with the community’s priorities and regional workforce needs, for starters.

Also crucial: Seeing partnerships like those Coffey created as part of the infrastructure needed to sustain the program over time, Howard says. In addition to creating the kind of seamless pathways Valley’s students enjoy, having community partners makes teachers’ jobs more sustainable.

In short, school system leaders will have to figure out how to do what Coffey did — banging on employers’ and union locals’ doors to ask about opportunities — in a more systematic way.

Here, too, the welding teacher may have paved the way. In addition to Local 49, he forged partnerships with carpenters unions, the UA Local 412 Plumbers and Pipefitters and several of the businesses that employ the unions’ members. These arrangements piqued the interest of the state Department of Workforce Solutions, which Coffey says is contemplating creating summer pre-apprenticeships.

Getting a leg up on entering the workforce or pursuing a degree is one goal. But Albuquerque leaders say they believe students will find the model more engaging, be more likely to show up for school consistently and ultimately get better academic outcomes.

Kids who find the engineering program are often square pegs, says Cassandra Gonzales, the assistant principal who oversees the career track. Some want to continue STEM studies they started in elementary or middle school. Others have struggled academically or floundered at large, traditional high schools.

May graduate Signe Conley is now on a fast track to medical school. But when she showed up in Coffey’s classroom in ninth grade, her highest ambition was to make herself invisible.

“I didn’t want to talk to anybody,” she says. “I was scared of everything.”

Her mother signed her up for welding but then emailed the teacher and asked him not to call on Conley or make her do anything, lest the girl have panic attacks. Coffey received the email as a gantlet dropped.

He handed Conley a stick welder, a tool that is both basic and finicky. He showed her how to make the electrical arc that generates enough heat to join two pieces of metal in a precise weld.

“It was loud, overwhelming,” says Conley. “Sparks were flying.”

The girl’s family tends 1,600 head of cattle, so Conley got plenty of practice fixing cattle guards and gates and other things on their ranch. The ability to control molten metal changed her.

She stayed in Coffey’s class but enrolled in a dual college program in nursing at another Albuquerque high school. In the fall, she will use the credits she earned to jump-start the process of earning a bachelor’s in nursing at the University of New Mexico, which will in turn give her preferential enrollment at the university’s medical school.

Junior Tobias Romero has also stayed in Coffey’s program even though he’s not pursuing an apprenticeship. He likes making metal art, and he is happy he has welding as a backup possibility for earning money. But his plan is to get a Ph.D. and work in New Mexico’s aerospace engineering industry. He’s gunning for an internship at NASA’s White Sands Test Facility.

Coffey is perhaps proudest that Dominic Duran was among the new apprentices receiving a stole last spring. Two years ago, then-sophomore Duran announced he was dropping out and would enroll in a commercial welding training program.

“I said, ‘Dominic, why would you pay $40,000 to get a certificate?’ ” Coffey recalls. “ ‘I can help you get it for free.’ ”

A high school dropout himself, Coffey taught himself metallurgy. He bought a cheap welding tool at a hardware store and made a gate to keep his chocolate lab, Chuy, from escaping. Then he started turning random metal objects into art to give to friends. Soon, he was producing prototypes to be sold as décor in big-box stores.

After a health crisis ended that career, Coffey decided to become a teacher. As the boss of an in-school metal fabrication shop, he is both tough and committed to creating a second home for kids. He’s known for bringing homemade red chile stew to share for lunch — and for encouraging his budding metalworkers to apply their talents not just to industrial settings, but to making art.

As freshmen and sophomores, students have to meet his high standards if they want to be considered for a district-paid internship. Watching their junior- and senior-year classmates cash paychecks is a big motivator.

“I put the apprenticeship bug in kids’ ears their junior year, so by the time they are seniors they know whether they want to do it,” he says. “I just sit back and watch until then.”

In a bittersweet twist of recognition, last year was Coffey’s last at Valley. The unions he has built relationships with are so pleased that Local 49 offered him a job setting up partnerships with schools throughout the state.

Can Valley’s brave experiment survive the loss of its senior foreman, the guy who built its student welders’ reputation one cold call to a local at a time? Coffey, the person who goes in search of ways to ignite kids’ passions, is determined to see that it will.

This article was published with the support of XQ Institute.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter