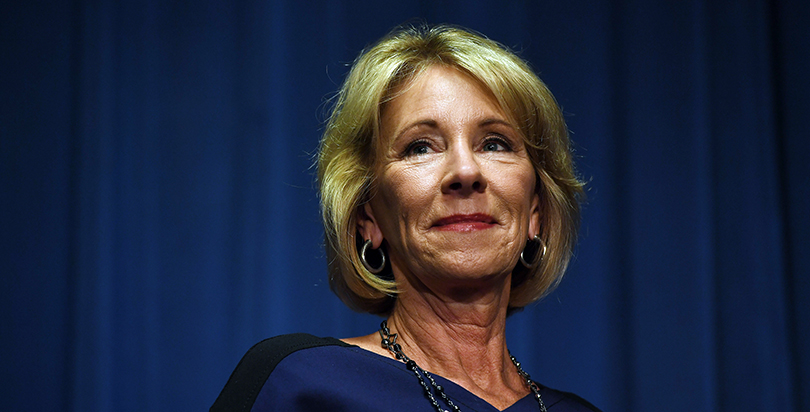

With No Senate-Confirmed Appointees, Who’s Helping DeVos Run the Education Department?

One of the main criticisms leveled at Education Secretary Betsy DeVos during her confirmation process was her lack of experience in education policy, and during her often-confrontational Senate hearing, she vowed to rely on department staff to help guide her in unfamiliar territory.

So far, though, DeVos is on her own. As of March 16, no one has been announced or formally nominated to fill the 14 posts within the Education Department that require Senate confirmation, such as general counsel and deputy secretaries. That is much slower than the Obama administration and, former officials say, impairs the department’s work in important ways.

“You would think that this administration would be working really hard to get people in place very quickly because it was very obvious that [DeVos] did not have a lot of expertise about school systems, postsecondary systems, or the specific federal programs she’s charged with implementing,” said Carmel Martin, who served as assistant secretary for planning, evaluation, and policy development under President Obama. Martin is now the executive vice president for policy at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank that has sharply criticized the Trump administration.

Most previous secretaries didn’t have experience in the federal government, said Gerard Robinson, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and formerly part of Trump’s transition team for education.

“The fact that she’s got a lot more experience in management and in understanding complex organizations, this could be very helpful for her,” particularly in implementing the budget, he said. DeVos, a Michigan billionaire, is a major GOP donor and former Michigan Republican Party chairwoman. She founded the school choice advocacy group the American Federation for Children, and her husband’s family co-founded and co-owns Amway.

The Education Department press office did not answer a request for comment, and the White House declined to do so.

Waiting for direction

High-level staffing vacancies are not only an issue in the Education Department. As of mid-March, the Trump administration has not nominated anyone to fill 497 of 553 key positions requiring Senate confirmation, according to a collaborative project between The Washington Post and the nonprofit Partnership for Public Service.

At the same time, the Trump administration has installed hundreds of officials not subject to Senate confirmation across the federal government. These appointees, including 31 people at the Education Department, are in jobs that are supposed to last four to eight months, but have assumed “considerable influence in the absence of high-level appointees,” ProPublica reported.

President Trump previously told Fox News he thinks some of the Senate-confirmed posts can remain unfilled. On Thursday, he released his budget proposal, which calls for a $9 billion cut to the Education Department.

The 74 interviewed three former Obama administration officials who held Senate-confirmed positions: Martin; Deb Delisle, who served as assistant secretary for elementary and secondary education; and Catherine Lhamon, Obama’s second assistant secretary for civil rights.

All three said the career staff at the roughly 4,000-member department is excellent, but not having a Trump-appointed, Senate-confirmed leader at the helm of the department can leave staff lacking direction.

The Office for Civil Rights is currently one of the most hot-button areas after the Trump administration’s recent decision to rescind guidance requiring schools to let transgender students use bathrooms that match their gender identity.

(The 74: After Reported Opposition, DeVos Defends Ending Transgender Protections to Friendly CPAC Crowd)

The sheer amount of work the office oversees is daunting, Lhamon said. The assistant secretary for civil rights oversees 600 staff in 12 regional offices investigating allegations of discrimination based on sex, race, and other characteristics protected by law. At the end of December, the office had received 17,000 complaints in a year, and about 4,000 are open at any one time, Lhamon said.

“Without a confirmed assistant secretary, there would necessarily be questions for staff within the office about what the guidance and direction of the office will be,” said Lhamon, now the chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Delisle, who served as Ohio’s schools chief before her appointment as assistant secretary for elementary and secondary education, said the career staff could be in a “gray space” between implementing the previous administration’s priorities and waiting for guidance from the new leadership.

“They’re not necessarily eager … to jump into perhaps new work, or work that may be aggressive or complex, because they just don’t know what’s going to happen,” she said. “When policy decisions are in a holding pattern until that confirmation, I just think it creates unnecessary uncertainty.”

Delisle is now the executive director of ASCD, a group of superintendents, principals, teachers, and advocates “dedicated to excellence in learning, teaching, and leading.”

State leaders have approached the organization for help in implementing the Every Student Succeeds Act, she said. There’s been some “nervousness” about what will happen to state plans if they’re submitted before the Trump administration finalizes its priorities, she added.

The Education Department has since released its final template for ESSA state plan submissions, though it has yet to release guidelines for how they’ll be reviewed. Congress passed a resolution overturning the Obama administration's rules and barring DeVos from regulating in a similar fashion. Trump is expected to sign the measure.

There are also implications in higher education, Martin said.

She pointed to the borrower defense to repayment program, which allows loan forgiveness for people who attended colleges that deceived students or violated state laws. Doing so requires the approval of political appointees, she said.

There are thousands of students from Corinthian Colleges, shuttered in 2015, and ITT Tech, which closed last year, seeking loan forgiveness, Martin said.

(The 74: ITT Tech Isn’t Just a College Scandal. It Also Ran Charter Schools — and Left Teens Scrambling)

“Not having people in those decision-making positions could create a huge bottleneck of people who are seeking that help,” she said.

Behind schedule

The Trump administration is running well behind the Obama administration in identifying candidates for these posts and making formal appointments to the Senate.

Obama, for instance, announced his first appointees, Martin, in the evaluation and planning job, and Peter Cunningham, as assistant secretary for communications and outreach, on Jan. 30, 2009.

Martin’s and Cunningham’s nominations, plus candidates for general counsel and assistant secretary for civil rights, were received in the Senate on March 18, 2009.

Even though the confirmation process for Obama’s nominees was limited — the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee didn’t hold hearings for them, for example — it still took weeks until they were confirmed.

The time between when the Senate received a nomination (sometimes weeks after the administration announced it) and final confirmation was an average of 57 days for that first batch of sub-Cabinet Education Department nominees. The last of the nominees, Assistant Secretary for Postsecondary Education Eduardo Ochoa, was confirmed June 22, 2010.

That process has only lengthened over time, as partisan rancor in the Senate has become sharper.

Delisle said she was first approached by the White House in the fall of 2011. She was formally nominated in January 2012 and approved by the Senate in April.

Other second-term nominees had to be renominated (nominations expire if the Senate doesn’t act on them before adjourning for the year) before the appointee was ultimately confirmed.

Later in Obama’s second term, the Education Department did run with several key offices vacant for long amounts of time, sometimes intentionally and sometimes while nominees awaited Senate confirmation.

No one was ever confirmed to replace Martin after she left her post in 2013, for instance, though two people were nominated for the job.

And the administration also was willing to keep at least one job open. When Secretary Arne Duncan announced his resignation in October 2015, Obama at first said John King would take his place on an acting basis, rather than go through the Senate confirmation process. At HELP Committee Chairman Lamar Alexander’s urging, Obama did formally nominate King to the post, and he was confirmed last March.

Some administrations, including the George W. Bush administration, have moved more slowly in getting a full education staff confirmed, and some of the delays for DeVos can be chalked up to her own delayed confirmation process, Robinson said, and the enormous amount of attention she received.

“This is now more public, and so people think, ‘Oh, wow, it’s taken way more time than usual,’ ” he added.

Once the Trump administration does identify candidates, there’s little indication Senate Democrats will allow them to breeze through the chamber.

HELP Committee members, including senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, wrote to Alexander asking for confirmation hearings for “critical positions” in the Education Department.

An aide to Alexander told Education Week that he would consult with Sen. Patty Murray, the committee’s ranking Democrat (who didn’t sign the letter) and announce an “appropriate process to ensure that the secretary has the staff in place in a timely way to serve the nation’s students.”

The Democratic senators said they’re particularly concerned about those who will serve in higher education policy, given DeVos’s remarks at the hearing that she would defer to staff on those issues in particular.

There is precedent, they said, pointing to past confirmation hearings for some Education Department nominees in the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations.

“We have a solemn duty to our constituents, to our fellow senators, and to the country to ensure that experienced and qualified experts are guiding and executing our nation’s higher education policy, and we look forward to evaluating these candidates in a public forum before the American people,” the senators wrote.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)