How Texas Teachers Are Prioritizing Basic Skills as Instruction Time Gets Crunched During the Pandemic

San Antonio teachers are combatting pandemic learning loss with a surgical approach to keep young students at grade level, focusing on a core curriculum of must-have skills in reading and math.

Given the challenges of limited class time and distance learning during the pandemic, San Antonio educators know students are simply not learning everything they would in a normal school year, especially in the early grades.

So this year, educators are going deep.

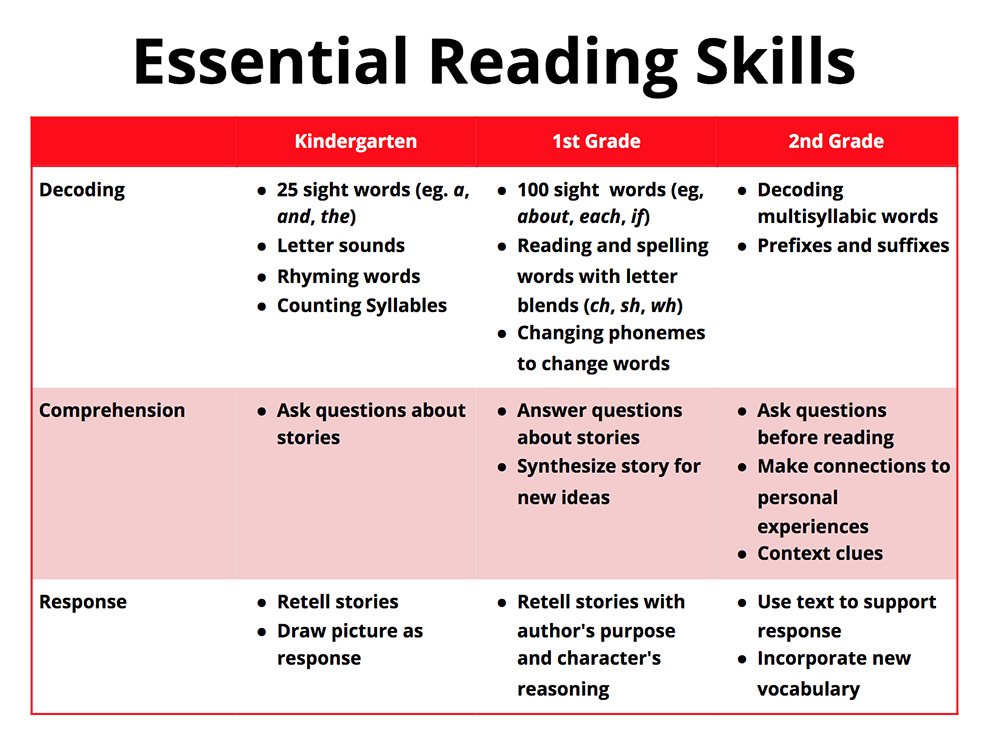

They have identified a strategic set of skills for kindergarten through second graders, such as phonics and arithmetic, so that students build the mastery needed to move on to the next grade.

Subjects like social studies and science that did not make top-tier priority haven’t totally gone by the wayside.

Teachers are relying on learning apps and online tools – something they don’t generally do in a normal year because it’s more effective to design and teach the lessons themselves.

“We knew we had to prioritize in order to stay on grade level,” said Olivia Hernandez, San Antonio ISD Assistant Superintendent for Learning, Language & Literacy.

To ensure kids learn to read, they’ve chosen to prioritize skills that help students decode words — like phonics and lists of words students should know. Comprehension is also being built through oral storytelling and read-alouds, drawing pictures of stories, and asking and answering questions about what was read.

The clarified priorities have also allowed parents to get more involved. Teachers are reminded to play to the strengths of what parents can offer, whatever their home circumstances may be.

For SAISD parent Sofia Erazo, sometimes that means listening to her 1st grade daughter read billboards as they drive the three and a half hours between their home in San Antonio and Houston, where her parents help her juggle remote learning for three kids, her own remote work, and care for the baby.

“Everything else is out the window,” Erazo said with a tired chuckle. “As long as you know how to count and how to read, you’ll get by in life.”

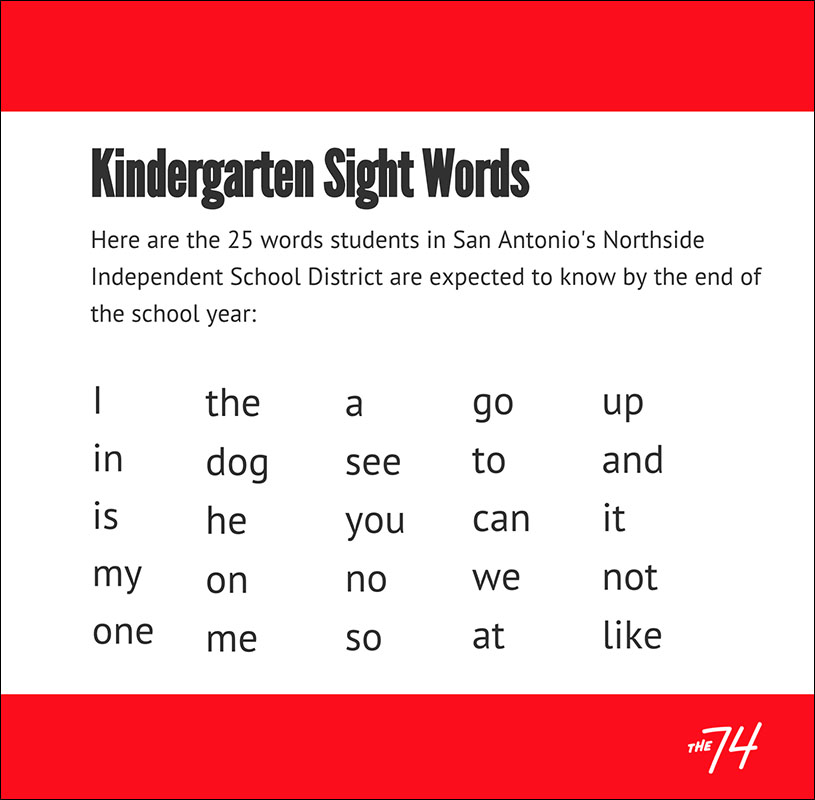

Elsewhere, Northside ISD Assistant Superintendent for Elementary Instruction Patricia Sanchez said educators started with 12th grade and worked their way backwards to select those skills most essential to staying on grade level the next year, Sanchez explained. “We were very focused.”

For other subjects, teachers are using apps like SeeSaw with social studies and science video lessons, with activities attached. The kids complete the activity and submit back to the teacher on the app. If a student struggles with the concept, the teacher can reach out to them directly to answer questions.

This leaves them free to spend valuable facetime on reading and math.

Teachers have less instruction time now than they did before the pandemic when every day consisted of 420 minutes in which they could instruct, review, and offer one-on-one and small group help.

In response to evidence that young children should not be tied to their screens for long periods of time, the Texas Education Agency does not require any live instruction for kindergarten through 2nd grade remote learners. While few schools have abandoned live instruction altogether for the age group, most agree the benefits of daily Zoom time top out at around an hour or two.

It was obvious from the beginning that reading instruction would be more important than ever, Hernandez said. Working to develop a pandemic-proof curriculum with the district’s master teachers over the summer, educators agreed that other subjects would be easier to recover later if the focus now stayed on reading, Hernandez said. “Setting a strong foundation in literacy is going to impact the other areas.”

So far, so good, she said. Beginning of the year assessments showed that the district has held its ground in reading, and mid-year assessments were “looking good” as well, she said. But the pandemic is still raging in Texas, meaning that an entire year of learning hangs on the continued success of these strategies.

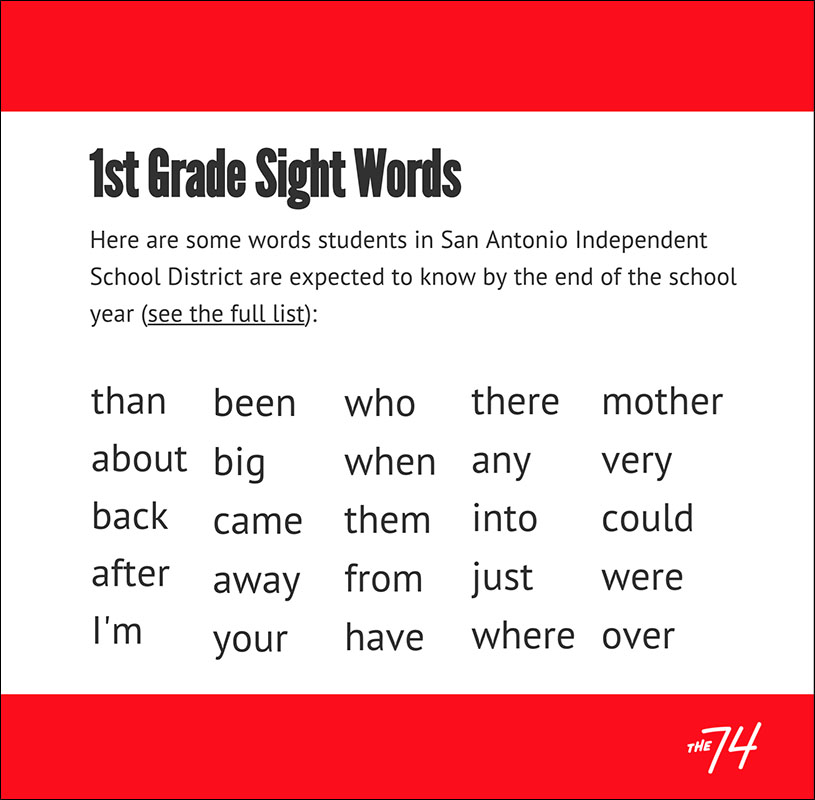

Districts paid careful attention to activities that can be reinforced at home such as identifying the sounds that make up words for household objects and connecting life experiences to new vocabulary words. Lists of sight words — words that show up frequently, or are tricky to sound out — can be downloaded from school websites or apps, printed or handwritten, and posted around the house.

Hernandez has emphasized asset-based thinking with her team: start with what the kids know, and build on what they have.

“If we approach this from a deficit mindset we’re going to shift into remedial mode,” she said. A remedial approach would have kids reviewing content from the previous year rather than learning what they should be learning in their current grade. Instead, she’s encouraged teachers to forge ahead on grade level, and to reinforce the weak skills as they come up.

Reading is different from math, another priority subject, which builds in a linear fashion, meaning students need to learn each discrete skill before moving on to the next. Counting leads to adding and subtracting, which both play a role in multiplication and division, and onward.

Literacy is an ascending spiral of skills. A second grader who is weak on something they learned in first grade will have the chance to strengthen it when the skill comes up again that year. For instance, familiar words with single-letter sounds like “do” and “to” will reappear with multi-letter combinations the next year to make those same sounds like “flute” and “through.”

For now, parents like Erazo are hoping that practice makes perfect, and getting as many words in front of their kids as possible.

In Houston, Erazo’s mom prints out worksheets for the kids while Erazo works remotely. At home in San Antonio she keeps a steady supply of library books and said she and her husband have spent quite a bit of money on Scholastic storybooks and puzzle books. The 1st grader must read one book out loud each day, often to her 4-year-old sister. In a rare pandemic win-win, she said, the 4-year-old has started to pick out sight words as the 1st grader reads aloud.

Her school district encourages parents to read aloud to their kids, and sent bundles of new books to each child over the summer. The focus on reading worked for her daughter, she said, and it’s a good thing, because Erazo is sometimes too tired at the end of the day to stay awake through a story.

“I no longer need to read to her,” said Erazo. “Now she reads to me.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)