With Digital Video Tools, Move This World Brings Social-Emotional Learning to a Wide School Audience

“I feel happy because my dad took me to the park,” one student said.

Another raised her hand. “I feel happy because my mom bought me donuts.”

“I’m feeling sad,” said a girl, who then whispered something to the teacher.

The teacher’s forehead creased. “I’m sorry,” she said, reaching out to the student. “We’ll talk about this later. Are you OK?”

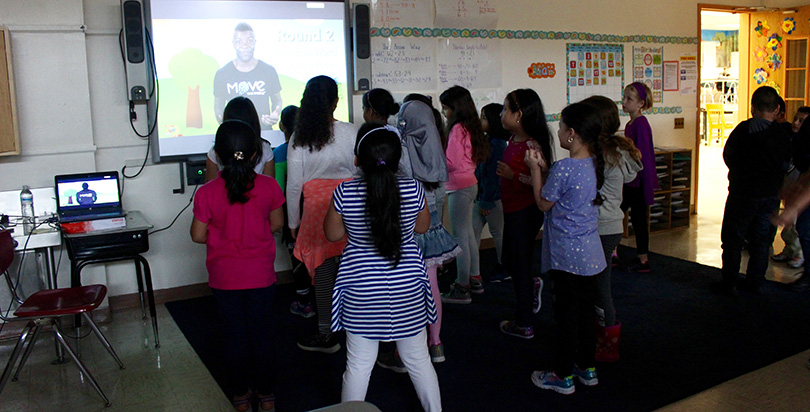

The preschoolers at The Renaissance Charter School in Queens, New York, had just finished watching a five-minute video that encouraged them to share how they felt. The students watch videos like this every morning and every afternoon as part of a social-emotional support program called Move This World. The rest of their elementary peers do this too, acting on research that shows how students’ emotions impact their academics.

“[The classroom] has to be a place where a child feels safe and valued. Otherwise, they’re going to resist being here,” said Rebekah Oakes, the school’s director of development and partnerships. “That comes out in, ‘I hate math. I hate this class. I don’t want to be here. What is this ever going to do for me?’ ”

Move This World, founded seven years ago, started using digital tools in 2015 to make it cheaper and easier for schools to access its social-emotional programs, which use the videos to teach pre-K–12 students skills for understanding and regulating emotions.

“How do we make these tools a seamless way to integrate care and compassion and bring this work to the forefront of teaching and learning that wasn’t burdensome, that wasn’t difficult to use, that was accessible for teachers who have a lot going on and may not have time for lesson prep?” said founder and CEO Sara Potler LaHayne, describing Move This World’s transition to the digital space.

In fact, a 2016 report from the World Economic Forum recommends using technology as a way to foster social-emotional learning, which not only is good for regulating classroom behavior but also teaches 21st century workplace skills like collaboration, leadership, and social and cultural awareness.

Move This World’s content, which is used in 42 schools and seven states, was developed in partnership with the American Institutes for Research and aligns with the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning’s recommended social-emotional core competencies: self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision making, relationship skills, and social awareness.

While the videos do not replace school counselors, they provide an easily accessible tool for addressing student emotions. They take up 10 minutes of each school day — five minutes in the morning and five minutes in the afternoon — and don’t require any preparation on the teachers’ end. The content varies depending on student age, with each grade watching the same clip for four to six weeks before moving on to new content. That will change next year, when the program introduces new videos in response to teacher feedback that students were ready to move on sooner.

The videos feature an engaging actor named Elliott, whom the students idolize with an enthusiasm reserved for rock stars, as he teaches tools for identifying, sharing, and regulating feelings. Elliott uses body motions to help the students act out strategies for staying calm, like counting to 10 or taking five deep breaths.

The first-graders at The Renaissance Charter School practiced these a few weeks ago.

“Say your name and how you feel,” education paraprofessional Daniela Vrsaljko instructed the class, copying the video’s instructions.

A student jumped up and stood at the front of the room. “My name is Ben and I feel cuckoo,” he said, wiggling his eyebrows.

“And what’s a solution?” Vrsaljko asked.

“Breathe five times,” Ben said, and moved his hands up and down, as Elliott had demonstrated in the clip.

Julian raised his hand to give an example of another strategy in the video: “Put yourself in someone else’s shoes.”

“What does that mean?” asked his classmate Iraklis. Julian slid off his chair and rolled around near his friend’s shoes.

“Not literally,” Vrsaljko said. “It’s about trying to see how someone else is feeling.”

Perhaps the most important aspect of the videos is that they provide a common language that students and educators throughout the building can use to talk about emotions, Oakes said.

Teacher Leah Shanahan has been at the school for more than five years and has seen the differences in her students before and after using Move This World’s videos. Before, when quarrels came up between children, tattling was the most common response. Now, students who don’t want to play or talk use phrases like “I don’t feel like talking today,” and the other kids respect that rather than bickering, she said.

Research supports this. The University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education, which tracks progress at schools that use Move This World, found a 60 percent decrease in suspensions and a 37 percent decrease in incidents of conflict from the 2013–14 and 2014–15 school years. Because this wasn’t a controlled trial, these improvements cannot be completely attributed to Move This World. However, the organization will start work on a controlled trial with the university next year to measure 215 classrooms in Metro Nashville public middle schools.

An earlier meta-analysis by CASEL found that students with social-emotional programs in their classrooms scored 11 points higher on standardized achievement tests than peers who didn’t have those programs. The 2011 report also showed positive SEL gains, such as better social behaviors and fewer behavior problems.

“They’re more aware not only that they have different feelings and emotions every day, but now they’re more aware from doing Move This World every morning that their classmates have different feelings, so that not all 25 of them feel the same way as you do, that everyone comes in every morning starting at a different place,” Shanahan said.

These social-emotional skills spill over into their academic life as well. Shanahan said her second-graders use vocabulary words they’ve learned about emotions to describe characters in books. Before the program, her students regularly used “happy,” “mad,” “sad.” Now, they might say “joyful,” “surprised,” “excited.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)