With Alexander’s Exit, Divided Senate Loses Quiet Champion of Bipartisan Approach to Ed Policy

When Tennessee Republican Lamar Alexander gave his farewell speech to the U.S. Senate last month, he recounted some of the major pieces of legislation he and education committee Ranking Member Patty Murray were able to move to the floor and ultimately to the president.

They include permanently funding historically Black colleges, streamlining the federal financial aid form — his most recent victory — and, of course, the 2015 passage of the bipartisan Every Student Succeeds Act, a bill, he said, “that had 100 alligators in the swamp.”

But when Murray, now poised to take his seat as chair of the education committee, recalls her favorite memories of Alexander, she thinks of him playing piano in the Senate office building atrium, accompanied by Democrat Tim Kaine of Virginia on harmonica. Alexander’s and Kaine’s musical collaboration began in 2014, they performed at a 2017 festival in Bristol — a town that straddles both of their states — and last month, they entertained Capitol staff with “Go Tell it on the Mountain.”

“Something about moments like that one show who he is as a Tennessean, and as a lawmaker,” Murray said, calling Alexander “someone who just enjoys finding ways to work with anyone — even when it comes to music.”

Alexander’s 18 years in the Senate, including six as chair of the education committee, came to an official close last week, days before rioters stormed the Capitol and invaded the chamber where he worked to advance key legislation. Many consider what he called “the bill to fix No Child Left Behind” the peak of collaboration during his tenure. With the Senate now split 50-50, the question is whether Alexander’s patient and non-polemical approach will continue under new education committee leadership. Murray, at least, has that goal in mind.

“Though there are too few elected officials that approach their job the way he did — with a focus on solving problems,” she said. “I’m hopeful that his legacy will continue in the … committee and we can continue to work in a bipartisan way to deliver for students and families.”

Forcing a ‘broad agreement’

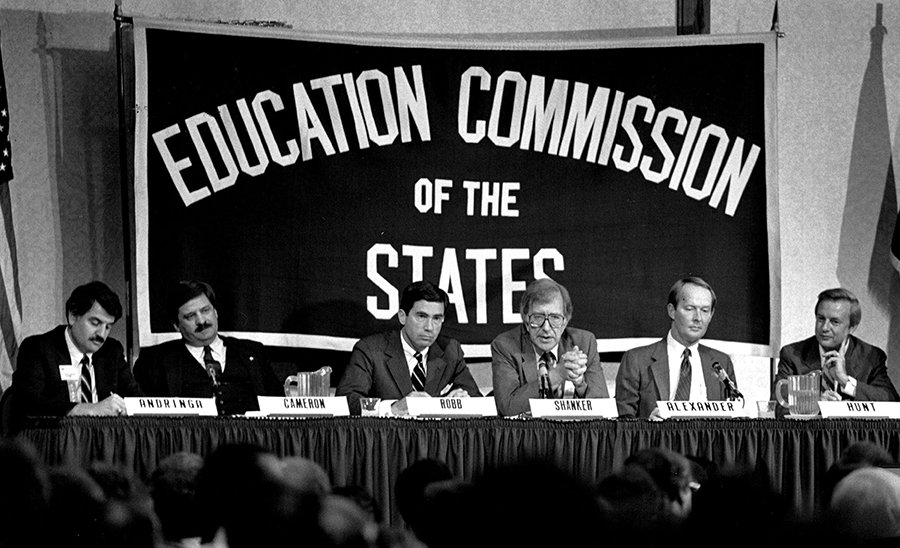

For Alexander, education has been an issue that unites rather than divides. When he became governor of Tennessee in 1979, he invited James Hunt, his counterpart in neighboring North Carolina, over for a visit.

He wanted Hunt, already established as an “education governor,” to talk to his cabinet about the Tar Heel State’s agenda on student achievement — policies such as setting minimum high school graduation standards and funding classroom reading assistants in the early grades. It didn’t matter that Hunt was a Democrat.

“He wanted me to make it clear to them that education was the most important thing they could work on,” said Hunt.

Reauthorization of the Perkins Act for career and technical education in 2018 was another milestone Alexander noted as an example of working with his Democratic colleagues. “It’s better, I think, to force a broad agreement on these difficult issues,” he said in an interview, “and then when we get it, it sticks.”

But even Alexander wasn’t able to find common ground with Democrats on other higher education issues, like Title IX, student loan repayment rates and applying accountability rules to for-profit institutions.

To him, leaving those fights for another day does not signal defeat.

“Part of his message to the U.S. Senate is that you can’t get everything you want, but what you can get is good enough,” said David Cleary, who worked for the senator for 15 years, most recently as chief of staff. In his farewell speech on Dec. 2, Alexander was “hoping to remind senators that they spend a lot of time and money and energy to get there, and there’s no reason for them to sit around like potted plants,” Cleary said.

‘A tricky issue for Republicans’

Whether as governor, president of the University of Tennessee, Secretary of Education during the first Bush administration or in Congress, Alexander can’t be accused of sitting around. To many observers, few people have had more influence over education policy for the past 40 years.

“He wrote the book about how to be a great United States senator focused on education,” said former Gov. Hunt. “He did it in a bipartisan way with the knowledge of a former governor who led education throughout his state and at the grass roots level.”

Alexander, whose parents were educators, made his mark early by taking on the controversial issue of teacher quality in his home state.

“He was a leader in emphasizing improved pay for teachers,” said David Mansouri, president and CEO of the Tennessee State Collaborative on Reforming Education, or SCORE. “So much of the past decade has been focusing on how we elevate and support great teaching in Tennessee.”

Under Alexander’s leadership as governor, Tennessee enacted a Master Teacher Program — among the first attempts to tie higher pay for teachers to stronger evaluations. The program was a forerunner of models that based evaluation ratings in part on student test scores, a reform largely opposed by teachers unions and that research later showed to be ineffective at boosting student performance. The Tennessee program lasted 13 years, and while it was associated with significant gains in reading and math, other results were mixed.

But while convinced that rewarding teachers for raising student performance was the “holy grail” of improving schools, he didn’t see it as the role of the federal government.

“He turned out to be right,” said Michael Petrilli, president of the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute, noting that the Obama-era policy of incentivizing states to factor student test scores into teacher evaluations “went too far.”

Alexander “embodied what makes education such a tricky issue for Republicans at the federal level,” Petrilli added. “We want to see major changes in our schools, but we also see that it’s very hard for the federal government to make sure those changes come out right.”

The teacher evaluation issue is what prompted Murray to begin working with Alexander on legislation to replace No Child Left Behind. Then-Secretary of Education Arne Duncan withdrew her state’s waiver from certain requirements of the law because officials weren’t using state test results to help evaluate teachers.

Ultimately, Petrilli said, the Every Student Succeeds Act “not only stopped that power from coming to Washington, but in real ways sent it back to the states.”

The ‘split screen’

Despite his reputation for bipartisanship, it was a partisan move — voting against calling witnesses in President Donald Trump’s impeachment trial last year — that some said will taint Alexander’s legacy as he retires to his home in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains. Without naming Alexander specifically, Democrat Bernie Sanders called the vote a “sad day in American history,” and Minority Leader Chuck Schumer expressed disappointment with his “Republican colleagues.”

Alexander’s vote, which ended the trial, was a rare moment when the senator received more attention for politics than for his preference, as Petrilli said, to “get things done.”

Alexander said he doesn’t “believe in giving advice” to his successors, but he did leave them with his favorite analogy to describe the institution where he ended his career in public office — a split-screen TV. The dysfunctional channel, he said, is tuned to the snarky tweets and tense confirmation hearings. But he’s tried to spend more time “on the other side of the split screen.”

Cutting by two-thirds the number of questions on the federal student application doesn’t amount to the kind of drama that pundits rehash during the evening news.

But “something that affects 20 million American families every year and makes it easier for them to go to college — that’s a very significant achievement,” Alexander said in the 74 interview. “There’s a lot more on the functional channel … than most people realize.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)