Winters: Does Expansion of Charter Schools Harm Nearby District Schools? My New Study Finds That No, It Doesn’t

As long as there have been charter schools, there have been those who have predicted that expanding the publicly funded but privately managed schools of choice would harm traditional public schools. They argued that charter schools would rob traditional public schools of resources and the most promising students.

A 2018 article in The Nation, for example, warned that charters are “the perfect weapon to destroy our public school system.” From my own experience, I recall being approached by a neighbor as I waited for a train to take me to the city from our wealthy suburb, with its famously excellent public school district. She handed me a leaflet and told me that voting in favor of a state referendum to allow charter schools to expand in areas where they had met their cap would be a vote against public education.

And yet charter schools expanded anyway. Between 2010 and 2016, the number of charter schools increased by 33 percent and the number of charter school students increased by 68 percent.

This expansion raises a question: If the Cassandras who predicted that charters would be the doom of public schools are right, shouldn’t the public school system be destroyed by now? But overall scores on the federal National Assessment of Educational Progress for students enrolled in traditional public schools have remained steady over the past decade. Indeed, many of the same folks warning about the negative impact of charters are the first to tell us that public schools are doing just fine.

Of course, charters haven’t grown at the same pace everywhere — they still enroll only about 6 percent of students nationwide, after all. But they have extensive market share within a small but growing set of localities; as of 2017-18, at least 30 percent of students in 21 districts were enrolled in charter schools. Perhaps the public school destruction has been limited to those districts that allowed the charter sector to run wild?

I shed light on this issue in a new report for the Manhattan Institute. I used a data set recently constructed by the Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis that tracks test scores for all U.S. public school districts from 2009 to 2016, adjusting for the fact that the states administer different tests. The analysis included districts with at least 10,000 students, which account for about half of the nation’s public school students.

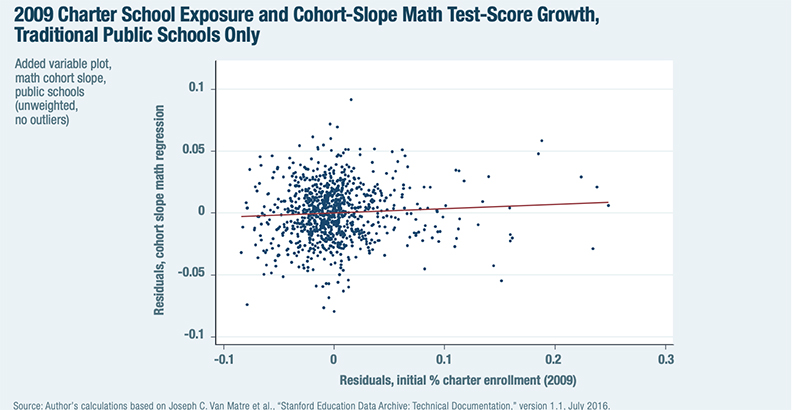

For the sake of the vast majority of students who remain in traditional public schools, I am relieved to report that the predicted demise did not occur. There is no distinguishable relationship between the percentage of students within a district who were enrolled in a charter school in 2009 and changes in the test scores of students enrolled in traditional public schools between then and 2016. Indeed, if a relationship exists but was too subtle for my model to detect, it is more likely that districts with high charter school concentrations made larger-than-expected gains over this period.

Importantly, the (lack of) relationship between charter school concentration and traditional public school gains over this period is evident whether charter schools compose a large proportion of the schools in the district or a small one. Among districts with very large charter sectors, some traditional public schools made meaningful gains while others saw declines. Among districts with little or no charter competition, similar numbers experienced increases and decreases in test scores. Remember that result the next time you read a news article linking the struggles of a particular public school district to local charter school expansion. While it is easy to find specific examples of areas with high charter school exposure and high/low changes in outcomes, when we take a broad view of the data, no clear relationship emerges.

To be clear: I don’t claim that my results prove that charter schools don’t impact the performance of traditional public schools. I can’t rule out that other factors might have systematically improved performance within districts that have also experienced charter school expansion. These data simply don’t provide me the opportunity for the type of analysis capable of making such a causal claim. (Though it’s worth noting that the several studies that do use such research strategies tend to find that exposure to charter schools either has no effect or a small positive effect on traditional public school quality.)

That said, the worst-case read of my results is that even if charter schools did hamper traditional public schools, those schools have responded in ways that at least counterbalance that negative impact. Under no scenario, however, can it be interpreted from the data that exposure to a highly concentrated charter school sector systematically destroys traditional public schools.

As we near our fourth decade of experience with charter schools, the burden of proof must shift squarely to those who would continue to argue that competition from charters is killing the traditional public school system. It hasn’t happened so far, despite rapid charter school growth. There’s simply no reason to believe it will happen in the future.

Marcus Winters is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, an associate professor at Boston University and the author of a new report, “Do Charter Schools Harm Traditional Public Schools? Years of National Test-Score Data Suggest They Don’t.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)