Why Is Illinois’s Governor Now Opposing His Own Commission’s Findings on School Spending? One Word: Pensions

It didn’t happen.

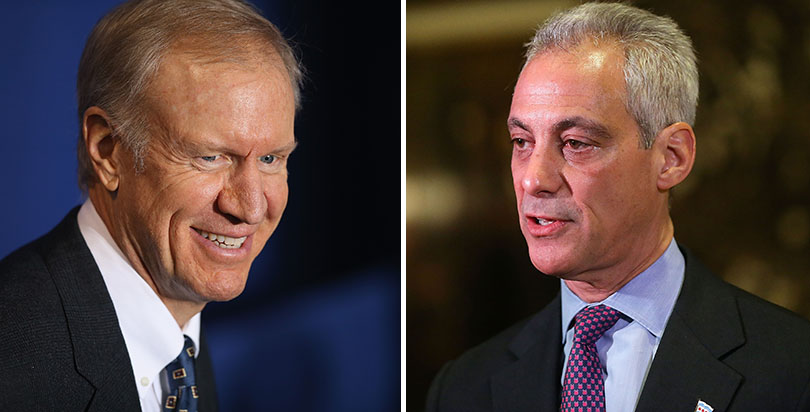

Instead, Gov. Bruce Rauner described the new funding proposal as a “bailout” for Chicago and, calling legislators to Springfield for a special session this week, vetoed provisions that included hundreds of millions directed to the nation’s third-largest school district. With the bill now back in the legislature, Speaker Michael Madigan, a Rauner adversary, must determine in the coming days whether he can whip enough House Republicans to overturn the veto.

In July, lawmakers were able to override Rauner in passing a budget after an impasse lasting 736 days.

There is little time to pass an education spending bill without disrupting the school year, which starts later in August. Schools are slated to receive their first state payments on Aug. 10.

Only a year ago there seemed to be a rare opportunity for consensus.

With the state’s high-poverty students receiving 20 percent less state and local funds — the worst gap in the nation, according to The Education Trust — Rauner commissioned a bipartisan panel, including five of his appointees, to come up with solutions.

“We have to win this,” he said. “Education is the key to a better quality of life.”

The commission concluded that Illinois would need to move away from reliance on property taxes and create an “evidence-based” formula that sent more to high-poverty districts. Current school budgets should be protected. The state needed to spend at least $3.5 billion over a decade to get to a fair dispensation.

These findings led to SB1, the new funding bill (which passed the legislature with almost no Republican support). Rauner now objects for two reasons that are familiar to everyone in Chicago and Springfield:

Chicago Public Schools has a massive $9 billion pension debt and is meeting payment deadlines by borrowing hundreds of millions at interest rates reflecting its junk rating.

Rauner calls the $221 million set aside in SB1 for CPS pension relief a “bailout.” He argues that the district already gets a disproportionately large share of state grant funding.

(Pension analysis: The Financial Catastrophe Looming Over Chicago’s Schools, in 6 Numbers)

“They can either choose a block grant or the pension, but they can’t do both,” he says. He said SB1 “places the burden of the Chicago Public Schools’ broken teacher pension system on our rural and suburban school districts.”

Rauner also vetoed a budget bill in December that would have sent $215 million to ease the burden at CPS. He blames its pension crisis on the irresponsibility of Chicago leaders in the decade following 1995, when a new education law went into effect that gave control of schools to the mayor. For many years, the city made few or no payments into the pension fund. As recently as 2001 the fund was solvent.

Because Chicago is the only district whose pension payments aren’t picked up by the state, however, Chicago officials, led by Mayor Rahm Emanuel, argue that city residents are “double taxed” — once to fund the pensions of the city’s teachers and again to fund the pensions of the rest of the state’s teachers. Additionally, the state is required to subsidize 20 percent of the city’s costs for non-CPS teacher pensions, which it has only done once. It has paid a fraction of that amount in recent years.

Block grants are one of the primary ways the state funds Chicago, like all Illinois districts.

SB1 would send $250 million to Chicago based on a 20-year-old formula that doesn’t reflect the substantial decrease in the city’s school population, as Rauner points out. After a year, however, CPS block funding would key into changes in student demographics.

“The only thing the governor’s action advances is his own personal brand of cynical politics,” said Emanuel, who unsuccessfully sued Rauner for inadequately funding the education of students based on race. “It is well past time for Gov. Rauner to stop playing politics with our children’s futures, start demonstrating leadership, and ensure a child’s education isn’t determined by their ZIP code or his political whims.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)