Why a New Brand of Cyberattack on Las Vegas Schools Should Worry Everyone

Infamously weak student passwords, a TikTok disclosure, parent threats and media leaks fueled a massive hack on America’s fifth-largest district.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

It was a Thursday morning when Brandi Hecht, a mother of three from Las Vegas, woke up to an alarming email from a student in another state whom she’d never met.

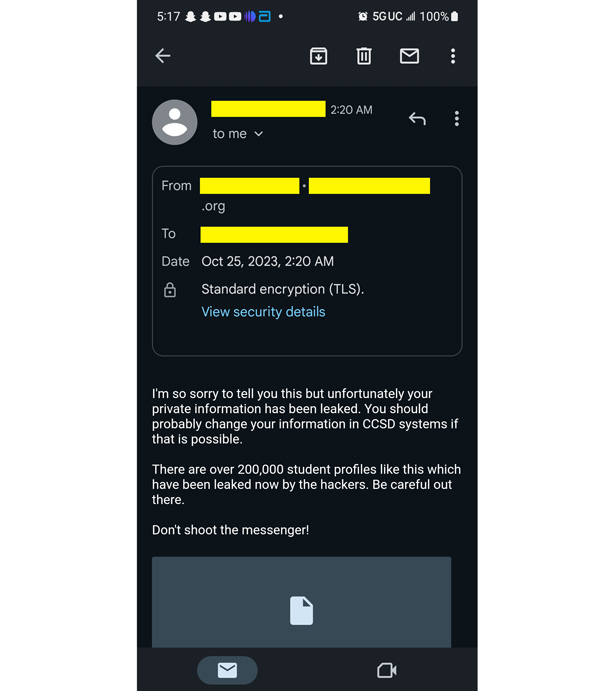

“I’m so sorry to tell you this but unfortunately your private information has been leaked,” read the email, sent to Hecht in the middle of the night Oct. 25 from an account tied to a school district in California. Attached were PDFs with personal information about her daughters including their names, photographs and the home address where they’d just spent the night asleep.

“Be careful out there,” the cryptic message warned. “Don’t shoot the messenger!”

Some 200,000 similar student profiles had been leaked, the email claimed, following a recent cyberattack on Clark County School District, the nation’s fifth-largest district and where Hecht’s three daughters are enrolled. But the message, she’d soon learn, was not from a California student but from the student’s email account, which had also been compromised. An unidentified, publicity-hungry hacker was using it as a “burner” account to brazenly extort Clark County schools by frightening district parents directly.

“I put my child on the bus and then immediately called the district,” Hecht told The 74. “I called the school, they transferred me to the district, the district transferred me to their IT department, who then transferred me to the help desk. I have yet to hear anything back.”

The Clark County threat actors claim their in-your-face tactics, which apparently involve not just direct outreach to parents, but also to media outlets, is already being used against at least one other district. Also distinct from other recent K-12 ransomware attacks, including high-profile incidents in Los Angeles and Minneapolis, the Vegas school district hackers claimed to use weak passwords — in this case students’ dates of birth — and flimsy Google Workspace file-sharing practices. Deploying those relatively low-tech incursions allowed them to gain access to reams of sensitive files, including students’ special education records.

Schools nationwide rely heavily on Google Workspace to create, and share records and the methods the hacker used to exploit district systems, a cybersecurity expert said, offer valuable lessons for all of them.

“This is not going to qualify as sophisticated hacking,” said Doug Levin, the national director of the K12 Cybersecurity Information eXchange, and is perhaps a sort of brand-building exercise. “Given that they reached out to the media” and have demanded payments smaller than those typically leveraged by ransomware gangs, “it seems they may be more interested in publicity and reputation than they are money.”

For Las Vegas educators, the hack has already brought significant consequences, including a class-action lawsuit and calls for Superintendent Jesus Jara to resign.

Clark County school leaders first confirmed on Oct. 16 that they became aware of a “cybersecurity incident” on Oct. 5, noting in a statement that it was “cooperating with the FBI as they investigate the incident” and that such attacks against schools have become routine. “Rest assured that we will share information as it becomes available so everyone is informed and can respond to protect personal information.”

When contacted by The 74, a Clark County spokesperson declined to comment further and shared a copy of the district’s previous statement.

Yet as Hecht and others accuse the district of failing to inform parents about the extent of records stolen, much of the information being revealed about the data breach has come from the threat actor themselves, including taunts that they were still in Clark County’s computer systems. In two follow-up emails shared with The 74, Hecht was sent web links that purportedly included troves of sensitive information about students including disciplinary records and test scores.

In an Oct. 26 message to Hecht, threat actors this time used a Clark County student’s email address “to show how much of a joke their IT security is and to show how seriously they are taking this.”

Beyond outreach to parents, the hacker — which could be one or multiple people — sent files to the local Fox TV station on Oct. 25 without solicitation, first communicating with a reporter via Facebook. Identifying themselves as “SingularityMD (the hacker team),” the threat actor disputed Clark County’s statement that it had detected “a security issue” on its own and that district leaders had only become aware after the hackers sent an email “to tell them we had been in their network for a few months.”

A hack with TikTok origins

Perhaps most revealing are communications between the hacker and a cybersecurity researcher at the blog DataBreaches.net, where the threat actor divulged their techniques and offered advice on how other districts can protect themselves.

In recent years, cybercriminals have gravitated toward “double-extortion ransomware” schemes, where they gain access to a victim’s computer network, often through a phishing email, download compromising records and lock the files with an encryption key. Criminals then demand the victim pay a ransom to unlock the files and stop them from being posted online. Yet in this case, the threat actors appear to have skipped past the first part and are employing an extortion strategy that centers exclusively on holding students’ sensitive information hostage.

For years, the 325,000-student Clark County district, whose systems were also breached in 2020, has reportedly reset all students’ passwords to their birth date at the beginning of each academic year. Using a student’s date of birth as a password has long been viewed as an insecure practice. In the case of Las Vegas schools, hackers claim the breach began on TikTok, where a student shared their birth date. The student used their district email address to create a TikTok account and their student ID became their username on the social media platform.

Once the hacker used that information to compromise the student’s account, they claim to have exploited poor data-sharing practices in the district’s Google Workspace to access the sensitive files. The compromised account was used to access information available to any student, which in turn offered records that allowed the hacker to escalate the breach until they were able to access administrative files.

“Google groups and google drives, if not configured correctly will expose teachers and staff files and conversations,” the hacker told DataBreaches.net. “In rare instances teachers have created shared drives and given the google group access to this drive. So if one was to add themselves to the group, they can then also access the drive contents. Nothing fancy at all.”

Schools are particularly easy targets because so many students have access to a district’s computer network, the hacker noted, with a word of advice: “I would recommend school districts separate the student network from the teacher network to make this process harder for teams like us.”

The same technique, the hacker claims, was used recently to compromise records maintained by Jeffco Public Schools in suburban Denver. In Nevada, SingularityMD says it demanded a ransom of roughly $100,000 versus just $15,000 from the 77,000-student Colorado district.

Federal law enforcement officials generally advise cybersecurity victims against paying ransoms, which can embolden hackers and spur future attacks. In the last year, ransomware attacks against the education sector have surged by 80%, according to a recent report by the nonprofit Institute for Security and Technology, which observed an uptick in incidents immediately after hackers succeeded in securing payments.

Levin said the hacker’s breach methods should set off alarm bells for educators nationwide, with “virtually every school in the U.S.” relying on cloud-based suites, like Google Workspace, to create and share content internally, with parents and with the public.

“It’s very easy to overshare information and grant rights for people who shouldn’t be able to see this information,” Levin said. “That’s what it looks like happened in Clark County is they got access to some student accounts, found some shared folders and in the shared folders was more sensitive information that allowed them to escalate privileges and get to even more sensitive information.”

Google spokesperson Ross Richendrfer said in an email that as districts become “a top target” for cybercriminals, “there’s not just one way that attackers attempt to infiltrate schools.” This particular incident, he said, was “the result of compromised passwords and configuration issues at the user/admin level.”

He pointed to the company’s K-12 Cybersecurity Guidebook, which notes that while Google products “are built secure by default, it is critical that admins also properly use and configure networks and systems to ensure security.” The guidance also recommends that districts train teachers and staff on best practices around file sharing.

In response to an email request, a Jeffco Public Schools spokesperson shared a Nov. 1 statement acknowledging the breach, which noted that staff members had received “alarming email messages from an external cybersecurity threat actor.” The district is working with outside cybersecurity experts and the police to determine the scope and credibility of the attack.

With respect to the emails from the California student, it appears the hacker used a compromised account associated with the roughly 4,440-student Coalinga-Huron Unified School District in Fresno County merely to communicate with other victims. The threat actor said that compromised student email addresses are used as “burner accounts” when they are not useful in escalating permissions beyond the student level.

Still, the district has conducted an assessment of its systems to ensure that it also hasn’t become the victim of a data breach, Superintendent Lori Villanueva told The 74. She said the student’s email address was used to send four emails, which were then deleted.

“We canceled that email account, we set up a new one for the student, and we’re just running our own diagnostics to make sure there was no other unusual activity,” Villanueva said. Allowing students to choose their own passwords can have drawbacks, she said, if they settle on weak credentials. “My people have been in contact with the Clark County school district and are trying to cooperate with them as much as we can but we’re really limited to that one tiny piece of information.”

Never before had she experienced an incident where a student’s email address was compromised and exploited in such a major way, she said.

“Nothing this widespread, nothing in another state, nothing this big,” she said. “For our little neck of the woods here, this was a little crazy.”

Reputational damage

For Hecht, the Las Vegas mom, the cyberattack in Clark County is deeply personal. In fact, she has a hypothesis about why she, in particular, received direct communication from the hackers.

In 2021, her daughter Harli was the subject of numerous news reports when she contracted COVID and never recovered.

“The only thing I can think of is somebody knows that I’m not quiet, that I will talk,” she said. If the hacker’s goal was to get Hecht fired up, it worked. The district, she said, needs to be held accountable for a failure to protect her children. Still, she said she hasn’t been able to get any answers from school administrators.

“I’ve emailed the superintendent and I just continue to call that helpline,” she said “Nothing. Nobody has responded. I can’t even get through, it just rings and rings and rings. To me, that tells me there are so many parents calling.”

Hecht said she has since retained a lawyer, and a pair of other parents have already filed a class-action lawsuit against the district. The Oct. 31 complaint accuses Clark County schools of negligence, particularly in the wake of the 2020 ransomware attack. The lawsuit alleges the district has refused “to fully disclose any details of the attack and what data were accessed and were available for third parties to exploit.”

“We think the district should be held accountable for their failures and ideally they will be able to make a more secure network in the future and anyone who has been subject to these data breaches will get the proper identity protection provided by the district at a minimum,” attorney Steve Hackett, who represents the families, told The 74.

Among those calling for Superintendent Yara to resign is Nevada Assembly Speaker Steve Yeager, who charged the district with nontransparency.

In an email, a district spokesperson said that individuals found to be affected by the breach will receive data breach notifications in the mail and declined to comment on whether it had, or planned to, pay the ransom. The district’s refusal to pay a ransom after the 2020 breach led hackers to release Social Security numbers, student grades and other private information.

“As the investigation continues, we are committed to cooperating with agencies responsible for finding the responsible party and holding them accountable,” the statement said.

The district also offered a sharp rebuttal to calls for Jara’s resignation, specifically referring to its contentious relationship with the local teachers union: “Superintendent Jara will remain superintendent as long as the Board of Trustees desires him to do so,” the statement continued “No bullying pressure, harassment or coordination with the leadership of the Clark County Education Association will deter him from his job to educate over 300,000 students and protect taxpayer resources from those who wish to harm the district or its finances.”

Hecht said the release of sensitive files, like medical records and special education reports, is particularly concerning, with implications extending far beyond those of Social Security numbers and financial records. She offered a message of her own directly to the hackers.

“It worries me because this stuff is going to follow them for life,” she said. “Look, I know that our district is not great, but if you’re going to go against the district, don’t take our kids down with you. They did nothing wrong.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)