Whitmire: America’s Best Charter School Doesn’t Look Anything Like Other Top Charters. Is that Bad?

Boston, Massachusetts

A year later I returned, still looking to answer that question. I arrived a few days after the Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education voted to allow Brooke a high school so students from its current three schools can transition into a high school run with the same philosophy and results.

Said state Commissioner Mitchell Chester: “It would be hard to overstate the track record of educational performance (at Brooke).” Keep in mind, this green light to expand happened in Massachusetts, a state in the throes of the nation’s most bitter fight over charters.

This time I sat down with Steadman’s husband, and co-director, Jon Clark, who founded Brooke. Even an hour into the interview I was worried once again: Am I going to walk away and still not understand Brooke’s secret sauce (a horrible cliché, but it gets to the heart of it) that makes them the best charter school in Massachusetts, a state that boasts the nation’s top-performing charters?

Among charter founders, Clark is unique. Quiet, studious, not given to bragging, not out to conquer the world by sprinkling charters in every state or even outside Boston. He’s prone to crediting his wife more than himself and offers only general clues to watch for as I start my classroom observations. It’s all about the teaching, he advised me.

What school leader doesn’t say that?

At the moment, the advice didn’t seem particularly helpful. At the end of the day am I going to climb into a cab to head back to Boston’s Logan Airport still puzzling over how Brooke takes in a student population that’s almost entirely low income and entirely minority, and turns them into scholars with test scores that match students enjoying the privilege of growing up white in a wealthy Boston suburb?

Some top charters talk about closing achievement gaps; Brooke actually does it.

Here’s the challenge about Brooke: It’s a group of K-8 schools, essentially a mom-and-pop charter, a creation of Clark and Steadman. Aren’t the nation’s best charters supposed to emerge from prestigious charter management organizations such as KIPP and Achievement First?

There’s more to the challenge. Unlike many top charters, especially Rocketship charters out of California, a blended learning pioneer (creating personalized learning by leaning on computer-based instruction) that I followed for more than a year while writing a book, “On the Rocketship,” Brooke mostly eschews computer learning. No blended learning to be seen anywhere.

Why? Clark has yet to find a software learning program that impresses him. Brooke’s entire emphasis is on teacher quality. Why would you subtract from teacher time by sending students off for laptop instruction?

The challenge goes on. Unlike many “no excuses” charter groups which adopt a highly scripted instructional style that could be set to a metronome, Brooke is pretty laid back. There’s no heavy “culture” pressure here.

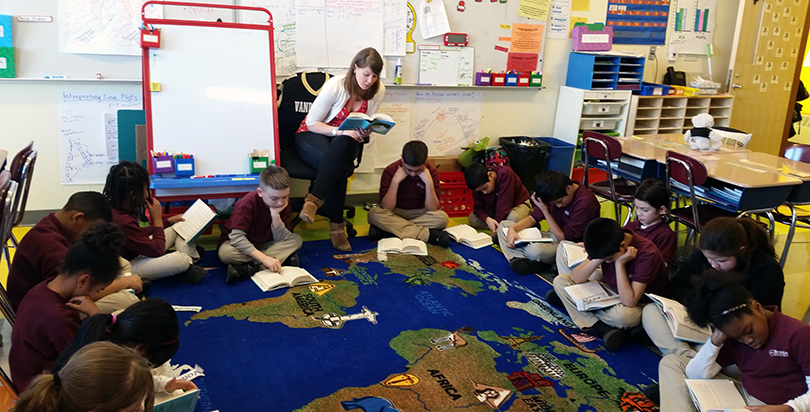

At Brooke, elementary students have carpeted squares they sit on for up-close-and-personal sessions with the teacher, but if a student happens to spill over into the next square there’s no command-and-control correction coming from the teacher, as I have seen in many “no excuses” charters. Yes, they file quietly through the hallways when changing classes, but nobody has to hold their hands behind their back or cupped in front of them.

In fact, if you suddenly forgot that every single student there comes from a non-privileged background, you could easily imagine you were in a private school where the students are somehow just naturally curious and well behaved, interested in every comment made by a fellow students.

Sounds intriguing, right? But how do they do it? I’m mid-way through my day-long stay here, and I still don’t have a real clue. Clark doesn’t make me feel any better when he advises me to watch classrooms for evidence of Brooke’s twin pillar philosophy in action: “challenged” and “known.” Challenged I get. But “known?”

The first insight into my unanswered question came as I tagged along with teacher Heidi Deck after she walked her fourth-graders across the street in very blustery conditions to physical education. One unique thing about being a Brooke teacher, she said, is that the instruction always starts with an unfamiliar problem, something the students haven’t seen before.

Deck went on to describe flipped instruction. In most math classrooms, teachers present a problem, demonstrate the solution and then have the students practice. It’s dubbed the “I do-we do-you do” method of instruction. Rinse and repeat.

Not at Brooke. Here, teachers start by presenting a new problem and then invite the students to solve it on their own, armed only with the tools from previous lessons. “We really push kids to be engaged with the struggle,” explained Deck.

Next, the teacher invites students to collaborate with one another in trying to solve the problem, which is followed by more individual attempts to solve it. Then there’s a classroom discussion about different ways students tried to solve it, with teachers doing their best to draw out solutions from the students. Ideally, they carry the weight of the instruction, learning from one another.

“The kids have to do the logical work of figuring something out rather than repeating what the teacher does,” said Steadman, who acts as the chief academic officer.

That posits math instruction more in the real world. Aren’t we always coming up against unfamiliar challenges, from calculating the wisest purchase to computing taxes?

And there’s another advantage: There’s no panic when Brooke students come across a math problem on the state exam they’ve never seen before. Instead they ask: What are the tools I already have to solve this?

Here’s another intriguing feature about Brooke: The reading scores here are as high as the math scores. That may not sound unusual, but it is. At almost any other top charter I visit that serves high-poverty students the math scores tend to soar while the reading scores are barely any better than neighborhood schools.

Why? The explanation always offered is that math gets taught in classrooms; literacy is more rooted in home life. Plus, in charters that rely on using computerized blended learning, the math software is great; the literacy software usually mediocre or worse.

The reason the math and reading scores align at Brooke comes down to a simple-but-radical approach to literacy: Reading is taught not as something mechanical (you will never see a reading worksheet at Brooke) but as something to be loved. In a traditional school, including charters, a child struggling with reading gets special help in breaking down the process into small pieces, with teachers searching for deficits that need correcting.

Brooke emphasizes phonics as much as any school, but on a broader level. A struggling reader at Brooke first gets asked: Why don’t you love reading? To the Brooke teachers, finding a way to unlock that love is as important, or more important, than isolating mechanical deficiencies.

“The goal is to get kids to love text so they become lifelong readers,” said Steadman. “Our kids do well on tests because they love reading.”

Yet another observation about Brooke. Visit any school in the country, charter or traditional, and the classroom walls will be full of colorful posters, student work and the daily academic goals. It wasn’t until about the third classroom I dropped in on that I noticed something different: At Brooke, the walls have that regular art but slathered over that are huge, jumbled tear sheets revealing classroom discussions about math, religion, history, a novel, pretty much anything.

These posters are chock-full of teacher scribbles of student comments, kind of like those Hollywood movies about math savants who fill blackboards with calculations. It all feels rich and creamy.

Take Deck’s fourth-grade classroom: The back wall is covered with tear sheets revealing elaborate graphs created with orange, blue, purple and green markers. There’s one labeled: Comparing decimals. Another: Divisibility rules. Another: What do I do with a remainder? On a side wall, two charts that break down a novel’s inner workings are partially covered by a tear sheet spelling out the players in the underground railway.

The complex wall arts points to one thing: Some serious and enthusiastic scholarship took place here. Here’s something else you notice about Brooke: There are a lot fewer students walking through the hallways. Actually, this is a pretty big difference (I may have saved the best for last.)

Brooke does something with its middle school grades that few others do. They structure them on an elementary school model, keeping students mostly in self-contained classrooms with the same teachers throughout the day. All those in-school shuffles between math, reading and science, prompted by soul-deafening buzzers. Not happening here.

Interesting story how that happened, and it’s all about Steadman. Or, to put it more precisely, it’s all about her husband, Clark, listening closely to Steadman, who arrived at Brooke in 2004 as a seventh-grade math teacher. Her prior experience had been as a fifth- grade math teacher. But really, she asked herself, how different could it be teaching seventh grade? As it turned out, a lot.

At that time Brooke’s older grades operated like a traditional middle school, where students changed classes to see teachers who specialized in math, reading or science. So Steadman taught nothing but math, class after class — and didn’t like it.

Aside from not getting to know the students that well, she missed the teacher collaboration she enjoyed in elementary schools where all the teachers who taught, say fourth grade, got together to plan what all fourth-grade classes should be studying that week. Wondered Steadman: Why should middle school be different?

After Steadman launched the elementary program, Brooke undertook an internal teacher survey that revealed something interesting: Elementary grade teachers reported more satisfaction than the middle school grade teachers. Why? Because of the teacher-to-teacher collaboration.

“It’s one of my big beliefs about how people work,” she said. “They like having thought partners, people they can talk to about the work they do. Being verbal about your work makes it more purposeful.”

So why not shift the middle school grades to the elementary school schedule? After a one-year successful pilot with fifth grade, Brooke flipped all its older grades to the self-contained model. Thus, teachers instruct all subjects, drawing on heavy collaboration with same-grade teachers. That guarantees a deeper relationship with the teacher, and also cuts down on the time students spend shuffling from class to class.

But the biggest benefit may be teacher satisfaction. Said Clark: “If you ask any teacher at Brooke to name the biggest thing that pushes you to get better, I think they would answer it’s having a smart colleague to co-plan with and look at data with.”

That self-contained model also helps explain the “known” part of the Brooke twin pillars philosophy: All students should feel well known by Brooke teachers, something more likely to happen in the nurturing self-contained classrooms.

All the above factors, woven together, account for the high performance at Brooke. Which raises this question: If the nation’s top charter school is headed in a direction different from other high-performing charters, is that a problem?

My answer: Only if you think all charter schools are supposed to look alike.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)