‘Do Not Underestimate the Ruthlessness’: White House Takes on K-12 School Cybersecurity Threat at First-Ever Summit

To ‘safeguard our children’s futures,’ First Lady Jill Biden says at event, ‘we must protect their personal data.'

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

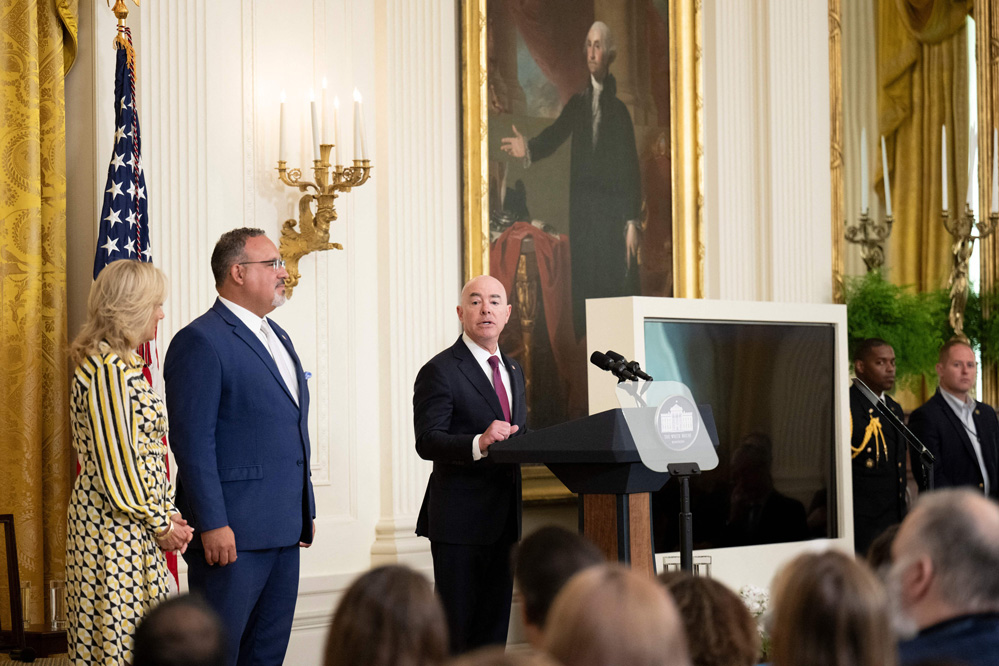

Shortly before First Lady Jill Biden took the podium at the White House Tuesday to champion a new federal initiative to combat K-12 school ransomware attacks, the cyber gang Medusa announced its latest victim on the dark web.

Such unrelenting attacks — this time against a Bergen County, New Jersey, district —are what brought the first lady as well as some 200 federal cybersecurity officials, school district leaders and tech company executives together for a first-ever White House summit on strengthening school district defenses.

“It’s going to take all of us,” Biden said.

The breaches have grinded school technology systems nationwide “to a halt,” the first lady said at the East Room gathering, forcing some districts to cancel classes as reams of sensitive student, parent and educator data were stolen and leaked online. In March, a Medusa attack on Minneapolis Public Schools exposed records about child abuse inquiries, student mental health crises and campus physical security details.

“If we want to safeguard our children’s futures, we must protect their personal data,” she said. “Every student deserves the opportunity to see a school counselor when they’re struggling and not worry that these conversations will be shared with the world.”

Among the new strategies announced Tuesday is the creation of a Government Coordinating Council that will provide “formal, ongoing collaboration” between all levels of government and school districts to prepare for and respond to data breaches. Officials with the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency said the agency would provide individualized assessments and cybersecurity training to 300 K-12 education entities over the next year.

Tuesday’s cybersecurity event didn’t come with the announcement of any new federal regulations but was instead positioned as the first step in a new-found federal urgency around cybersecurity in schools. The Federal Communications Commission in late July proposed a $200 million pilot program to enhance cybersecurity in schools and libraries that still needs to be approved.

“When schools face cyber attacks, the impacts can be huge,” Education Secretary Miguel Cardona said. “Let’s be clear, we need to be taking these cyber attacks on schools as seriously as we do the physical attacks on critical infrastructure.”

In a new report released by the Education Department and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, the agencies recommended that school districts implement multi-factor authentication, enforce minimum password strength standards and ensure software is kept up to date. They should also consider moving on-premises information technology services to cloud-based systems.

“Do not underestimate the ruthlessness of those who wish to do us harm,” Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said. “They have proven their willingness to steal and leak such private student information as psychiatric hospitalizations, home struggles and suicide attempts. Do not wait until the crisis comes to start preparing.”

School cybersecurity expert Doug Levin, who attended the summit, said it was a positive development to see the federal government, and the Education Department in particular, focus on the effects of ransomware on schools. The Education Department has been “mostly absent from these conversations” in the past, said the national director of The K12 Security Information eXchange.

Meanwhile, several companies, including education technology vendors, unveiled new commitments to help facilitate digital security in schools. Amazon Web Services announced a new $20 million grant program to bolster K-12 school cybersecurity while Cloudflare committed to providing free cybersecurity tools to small districts with 2,500 or fewer students.

Schools are now the single leading target for hackers, outpacing health care, technology, financial services and manufacturing industries, according to a global survey of IT professionals released last month by the British cybersecurity company Sophos.

In the U.S. school district cyber attacks reached a record high of 37 in the month of June alone, according to one tally, but Tuesday’s event centered largely on a crisis that unfolded in Los Angeles nearly a year ago.

Last September, a notorious ransomware group carried out an attack on the Los Angeles Unified School District, the nation’s second largest, that resulted in some 500 gigabytes of district data being published to the Russian-speaking group’s dark-web leak site.

A major theme of the White House summit was the politically connected superintendent’s swift outreach to federal agencies, including the U.S. Department of Education and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. That collaboration, Superintendent Alberto Carvalho and federal education officials said, set into motion a response plan that mitigated the attack, limited the number of files breached and avoided class cancellations.

Jen Easterly, director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, called it “the Harvard Business School case study on how to get this right.”

Other school districts should respond similarly, said FBI Deputy Director Paul Abbate. When school leaders suspect they’ve been the target of an attack, he said, it’s incumbent that they “please call us immediately.” In L.A.’s case, the FBI was able to have a team of agents on the ground in less than 24 hours, he said, enabling them to freeze vulnerable accounts and secure sensitive information that had been sought out by the threat actors.

That coordinated response didn’t prevent some 2,000 current and former students’ highly sensitive psychological evaluations from being leaked on the dark web, an investigation by The 74 revealed. Carvalho initially denied that such records were exposed in the attack, but the district acknowledged they were after the story was published. The district also initially said the attack began and ended on Sept. 3 — the Saturday of Labor Day weekend — but a follow-up investigation determined that an intrusion began as early as July 31, the Los Angeles Times reported.

While Carvalho didn’t comment Tuesday on the leak of sensitive psychological information, he said the number of stolen files “could have been much worse,” adding that the hackers “encrypted and exfiltrated very little thanks to our actions.” Among the actions they didn’t take, the schools chief said, was paying the undisclosed ransom demand because “we don’t negotiate with terrorists.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)